This is from Simon DaVison’s Snark film. I have his permission to offer this in public domain.

blog

Face it!

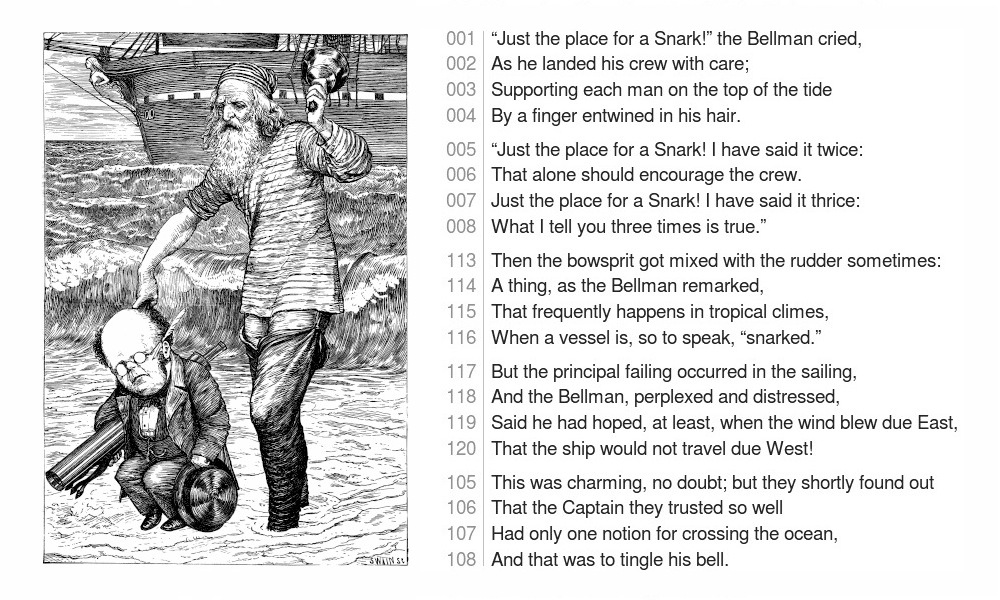

The Failing Occurred in the Sailing

“Just the place for a Snark!” the Bellman cried,

As he landed his crew with care;

Supporting each man on the top of the tide

By a finger entwined in his hair.“Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice:

That alone should encourage the crew.

Just the place for a Snark! I have said it thrice:

What I tell you three times is true.”

Then the bowsprit got mixed with the rudder sometimes:

A thing, as the Bellman remarked,

That frequently happens in tropical climes,

When a vessel is, so to speak, “snarked.”But the principal failing occurred in the sailing,

And the Bellman, perplexed and distressed,

Said he had hoped, at least, when the wind blew due East,

That the ship would not travel due West!

This was charming, no doubt; but they shortly found out

That the Captain they trusted so well

Had only one notion for crossing the ocean,

And that was to tingle his bell.

Sir Nicholas Soames’ speech | Repetition increases perceived truth | Code

2018-08-26, updated: 2023-05-06 (MG007)

ChatGPT understands the Bellman’s rule

Embedded Mastodon toot:

2023-04-16

Charles Darwin and the Snark

This is an excerpt from an email with which I responded to an enquiry related to Charles Darwin and the Snark.

=== Darwin ===

As a deacon and as a scientist Carroll surely was inspired by Charles Darwin and the naval expedition with the HMS Beagle. Probably Carroll also struggled with some of Darwin’s findings quite a bit. In {https://snrk.de/snark-hunting-with-charles-darwin/} you find links to my blog posts related to Darwin.

=== Tuning forks and lace needles ===

I think that in “The Hunting of the Snark” there might be references to two tools used by Charles Darwin: Tuning forks {https://snrk.de/snarks-have-five-unmistakable-marks/#tuningforks} for experiments with spiders (it’s still done today) and lace-needles (you see them in an illustration by Holiday) for dissection {https://snrk.de/page_vivisection/}.

=== The Banker ===

In “The Hunting of the Snark”, the characters could be references to more than one real life person. In 2013 I posted some musings about a “Snark Matrix”, but I didn’t follow up on that as it might be too speculative: {https://snrk.de/snark-matrix-2013/} and {https://snrk.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The_Snark_Matrix.pdf}. In Carroll and Holiday’s tragicomedy, several characters might be associated with Charles Darwin, with the Banker being among them: {https://snrk.de/tree-of-life/#Banker}.

=== Tree of life ===

I am struggeling with this one: {https://snrk.de/tree-of-life/}. There might be a reference to a drawing by Darwin in one of Holiday’s illustrations which later became popular as Darwin “Tree of Life”. “Later” means: After a facsimile of the Darwin’s sketch was published. But to my knowledge, that didn’t happen during Carroll’s lifetime. Also another source of inspiration could be possible: An eagle riding on a boar: {https://snrk.de/tree-of-life/#EagleOnBoar}.

2023-04-16

Chatting with ChatGPT about “boots”

- Could “boots” be a portmanteau for the two words “bonnets” and “hoods”?

- If the word “boots” would not yet exist, could “boots” be a portmanteau for the two words “bonnets” and “hoods”?

- Could Lewis Carroll just have decided to break the rule that while it is possible to create a new word through the process of portmanteau, it is not possible to simply assign a new meaning to an existing word by combining unrelated words.

- While ignoring any previous rules for portmanteaus, could Lewis Carroll just have decided to use the word “boots” as a portmanteau for the two words of “bonnets”and “hoods” without the intention to make the portmanteau successful?

2023-03-10

Snark Forum

2023-02-25

Please use https://groups.io/g/TheHuntingOfTheSnark

2021-12-16

My snrk.de blog has no forum. I don’t want do deal with privacy issues caused by storing user data. More important, I am too lazy to manage a forum.

But there is a nice (albeit presently not too active) Snark sub-forum managed by Mahendra Singh in thecarrollforum.proboards.com. It’s just the place to discuss Snark.

There you also will find some of my old posts. As I try to keep learning, I of course would write many of them differently today.

If you want to comment on anything you find in the web about The Hunting of the Snark, I recommend to open a thread in that forum, enter the link you are referring to in the post, and write there what you want to discuss.

2020-09-24, updated: 2023-02-25

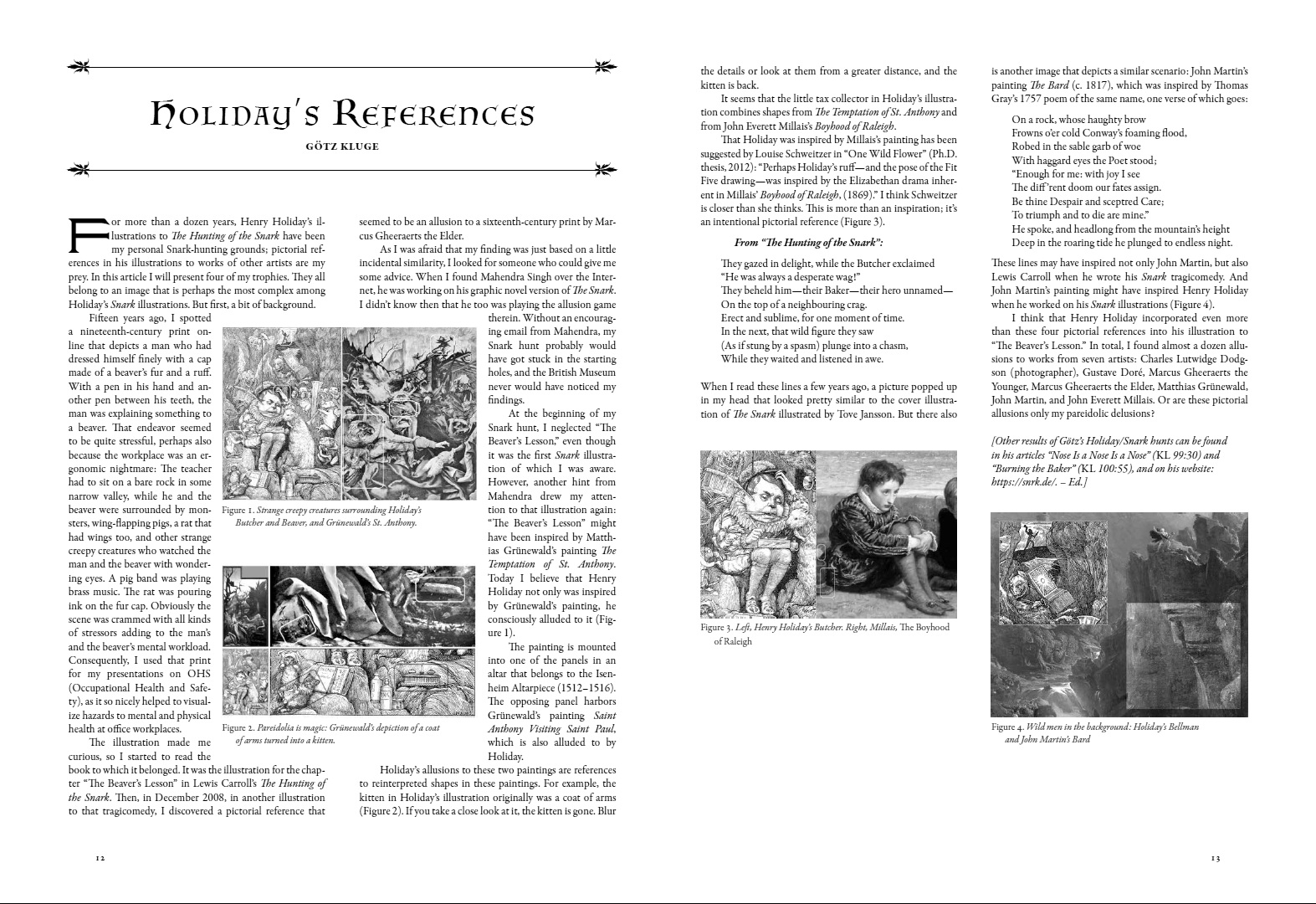

Meagre and Disjointed Extracts

In C.L Dodgson’s days, some members of the Anglican clergy were not happy with their 39 Articles (1563, revised 1571). And it seems that the Deacon Dodgson was not happy with these colleagues. He objected especially to the last article in Thomas Cranmer’s 42 Articles (1553), which didn’t make it into the 39 Articles. Dodgson did not accept the dogma of eternal punishment.

So I always was curious to learn more about attempts to restore the articles which were withdrawn from the 42 articles. I found an answer in Essays and Reviews: Richard Bethell 1st Baron Westbury thought of the 39 Elizabethian Articles of Religion as “meagre and disjointed extracts [from Thomas Cranmer’s 42 Articles] which have been allowed to remain in the reformed Articles”.

It is material to observe that in the Articles of King Edward VI., framed in 1552, the Forty-second Article was in the following words:-

“‘All men shall not bee saved at the length.’ —

Thei also are worthie of condemnation who indevoure at this time to restore the dangerouse opinion, that al menne, be thei never so ungodlie, shall at lengtht bee saved, when thei have suffered paines for their sinnes a certain time appoincted by God’s justice.”This Article was omitted from the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion in the year 1562, and it might be said that the effect of sustaining the Judgment of the Court below on this charge would be to restore the Article so withdrawn.

We are not required, or at liberty, to express any opinion upon the mysterious question of the eternity of final punishment, further than to say that we do not find in the Formularies, to which this Article refers, any such distinct declaration of our Church upon the subject as to require us to condemn as penal the expression of hope by clergyman, that even the ultimate pardon of the wicked, who are condemned in the day of judgment, may be consistent with the will of Almighty God.

We desire to repeat that the meagre and disjointed extracts which have been allowed to remain in the reformed Articles, are alone the subject of our Judgment. On the design and general tendency of the book called “Essays and Reviews,” and on the effect or aim of the whole Essay of Dr. Williams, or the whole Essay of Mr. Wilson, we neither can nor do pronounce any opinion On the short extracts before us, our Judgment is that the Charges are not proved.

Source: Excerpt (pp. 762-764 in ER) from Trial and Appeals, 1861 to 1864: “Erroneous, Strange, and Heretical Doctrines”, B “This Great Appeal”: Before the Judicial Committee if the Privy Council, III The Judgement [1864-02-08, by Lord Westbury] of the Lord Chancellor.

For comments: Mastodon | Twitter

2022-01-19, updated: 2023-01-21

Lewis Carroll: maker of wonderlands

Detour to Буджум

Please go to snrk.de/буджум/

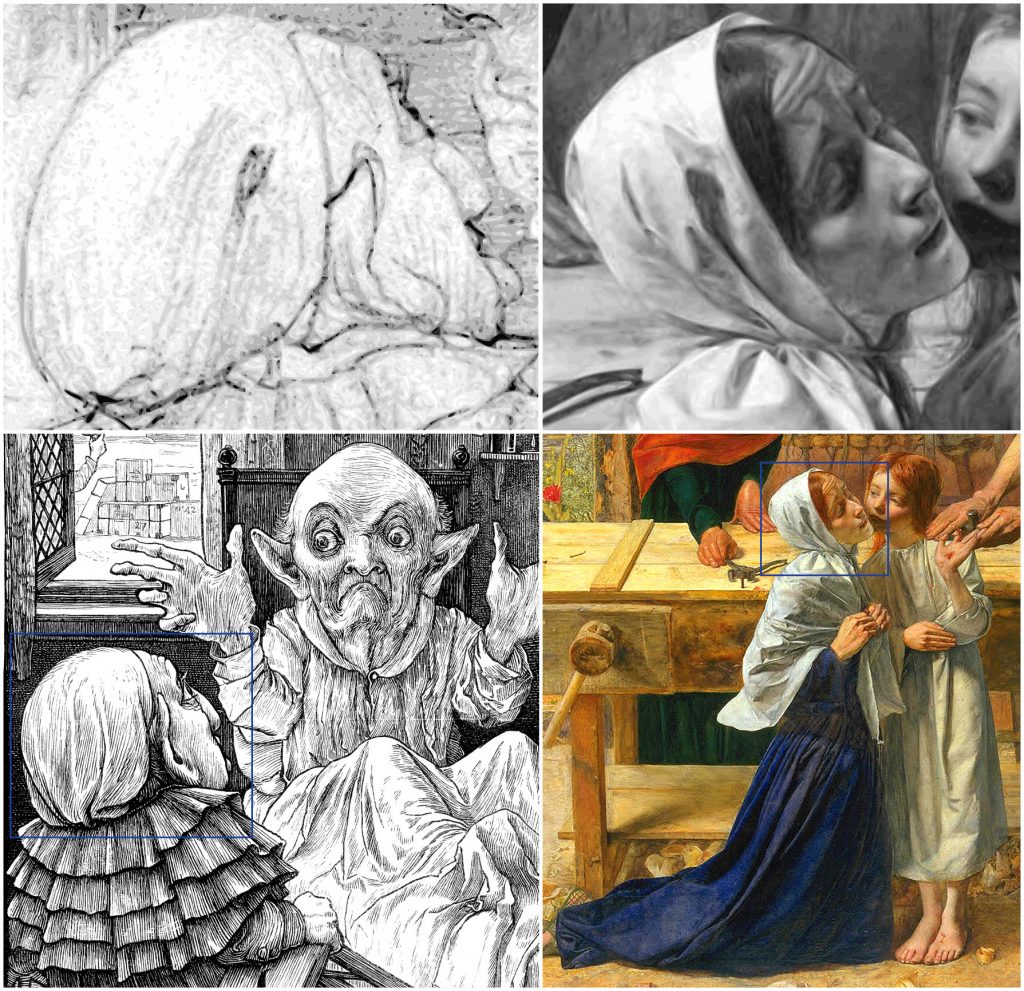

Hideously Ugly

Jun 13, 1862: Saw Millais’ “Carpenter’s Shop” at Ryman’s. It is certainly full of power, but hideously ugly: the faces of the Virgin and Christ being about the ugliest.

I found this quote in Lewis Carroll’s Diaries on Twitter.

And I found the following quote from Charles Dickens in Pre-Raphernalia, Raine Szramski‘s blog with “Pre-Raph Sketchbook Cartoons”.

You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England.

Two almost naked carpenters, master and journeyman, worthy companions of this agreeable female, are working at their trade; a boy, with some small flavor of humanity in him, is entering with a vessel of water; and nobody is paying any attention to a snuffy old woman who seems to have mistaken that shop for the tobacconist’s next door, and to be hopelessly waiting at the counter to be served with half an ounce of her favourite mixture. Wherever it is possible to express ugliness of feature, limb, or attitude, you have it expressed. Such men as the carpenters might be undressed in any hospital where dirty drunkards, in a high state of varicose veins, are received. Their very toes have walked out of Saint Giles’s.

Perhaps Dickens initially saw the reproduction of Millais’ painting in the Illustrated London News (1850-05-11) and couldn’t forget that first impression. It seems that the engraver of the reproduction was a bit biased against Millais’ Carpenter’s Shop. (Twitter | Mastodon)

Whether ugly or not, Henry Holiday probably liked the painting of his teacher. He might have alluded to Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents when he illustrated Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark.

Whether ugly or not, Henry Holiday probably liked the painting of his teacher. He might have alluded to Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents when he illustrated Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark.

Category: Christ in the House of his Parents

2019-06-14, update: 2022-12-29

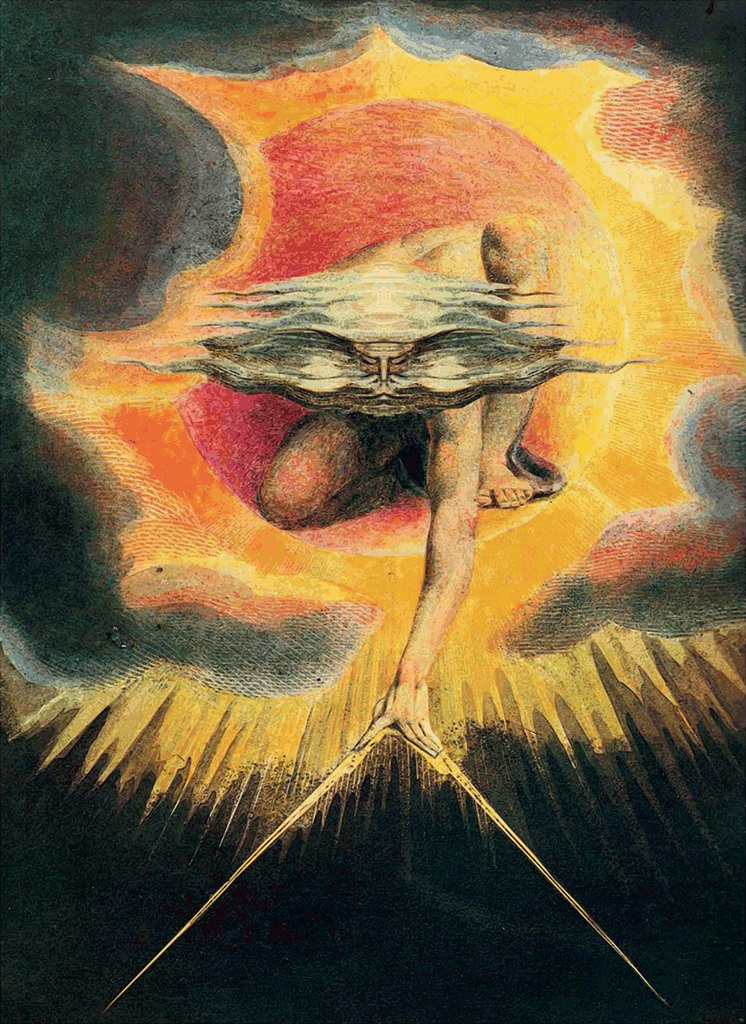

My Avatar

In this image you see where this avatar came from.

History: In 2017, my first avatar was based on a painting by William Blake.

This is a recombed version of Blake’s The Ancient of Times. Your family and your friends might enjoy them in high resoluton: Print them in color (8000×10000) and in black&white (8000×111111), frame them nicely, and give them away as a beautiful gift to keep up their spirits.

2017-08-28, update: 2022-11-14

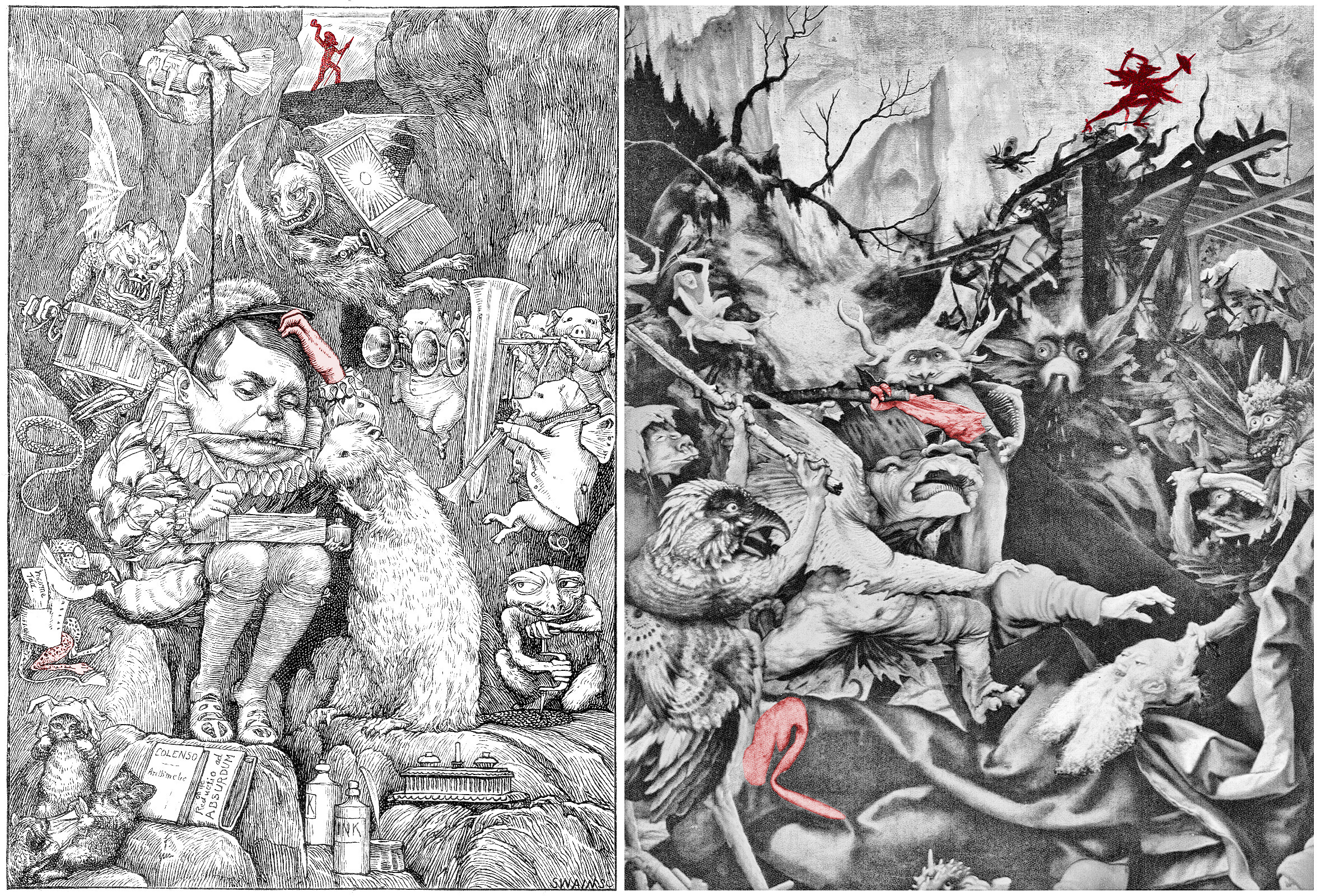

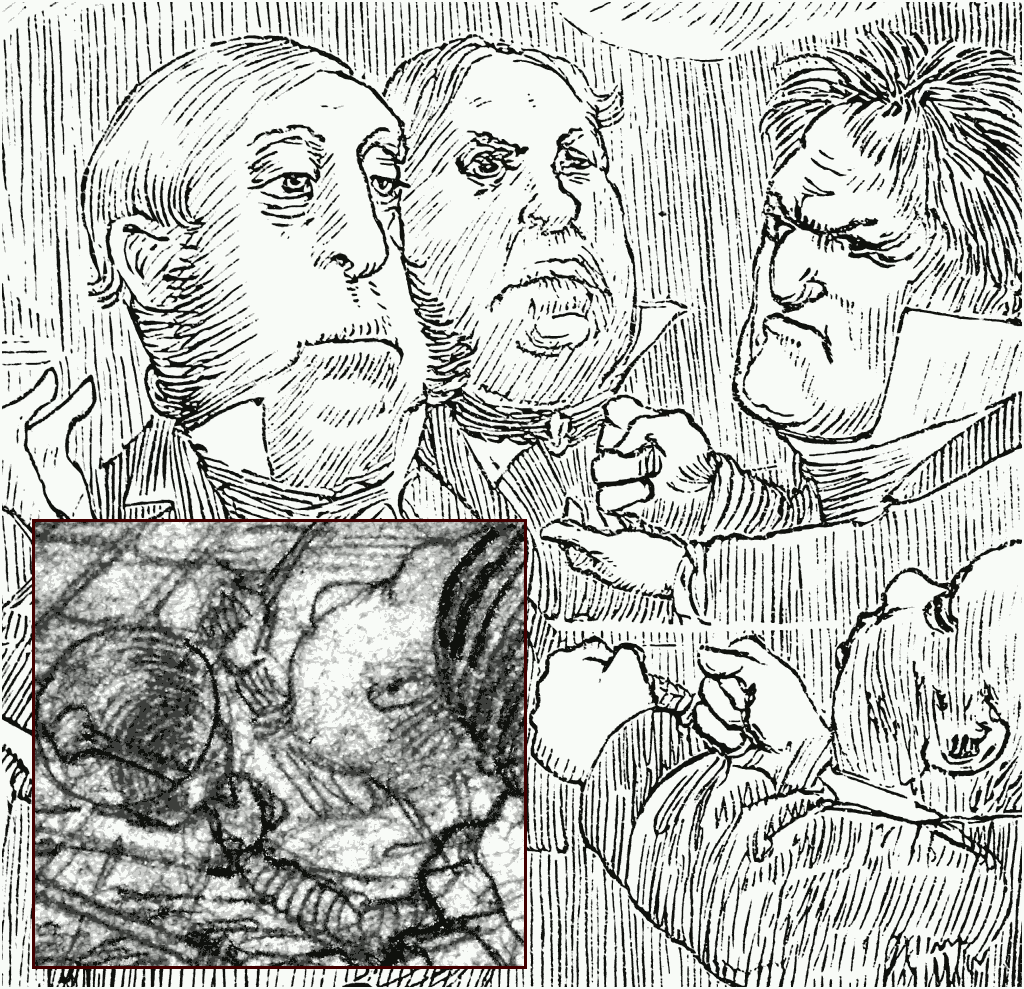

Snark too Dark

On the left side of this image comparison you see a scan (source: commons.wikimedia.org) of Henry Holiday’s illustration to the final chapter The Vanishing in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark. It already is a quite faithful reproduction of the original illustration.

The image on the right side has been generated from a scan of an original illustration from my own 1st edition of The Hunting of the Snark, where I grew the white areas a bit. (First I enlarged the image by 2:1. Then I applied GIMP → Filters → Generic → Delate. After that I scaled the image back to its previous size.)

I am not sure whether in the original printing from electrotypes the dark areas of the illustration might have grown wider than it was intended by Henry Holiday. It looks as if too much black ink had spilled into the white areas.

As for resolution, the print made by Ian Mortimer (for a limited edition of The Hunting of the Snark published by Macmillan in 1993) from Joseph Swain’s original woodblocks has a better quality than the illustration which you find in the mass printed books. But Mortimer’s print looks even darker.

In order to fix overprinting with the technology available to in the 19th century printers, one perhaps would have to redo the electrotypes and then try to erode the black areas using etching. Or just less ink would just do the job. But I don’t know too much about electrotyping (and printing in general), so I am just guessing here. Whatsoever, since many Snark editions hade been sold already, the dark Snark with the well hidden face of the Baker is the standard today.

Further reading: Lewis Carroll’s cat-astrophe, and other literary kittens by Mark Brown, The Guardian, 2018-11-22. (A tweet by Susan J. Cheadle drew my attention to that article. “Carroll’s Trump-like anger at the printing of his book Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice Found There is revealed in a new exhibition opening at the British Library which explores and celebrates cats in literature.” (As for cats, you might like my blog post “Kitty”.))

2021-06-05: Today I learned that on 1876-03-02, Macmillan reported to Carroll that the block for the illustration for the 8th fit was not printing clearly. Source: p.17 in The Snarkologist, The Institute of Snarkology, Vol. 1, Fit 1, May 2021, referring to p.124 Footnote 1 in Morton Cohen and Anita Gandolfo’s Lewis Carroll and the House of Macmillan, 1987. So I suggest, that from now on Snark publishers use a corrected version of the illustration for the 8th fit.

2018-06-17, updated: 2022-11-25

Snarkology

- ☞ The Institute for Snarkology: snarkology.net

- 2021-06-05: Already the first Vol. 1, Fit 1 of The Snarkologist helped me to confirm an assumption.

- Books & Papers for Snarkologists

- Mastodon: @snarkology@zirk.us

2021-06-08, update: 2022-11-14

The Bandersnatch fled

as the others appeared

509 The Bandersnatch fled as the others appeared

510 Led on by that fear-stricken yell:

511 And the Bellman remarked “It is just as I feared!”

512 And solemnly tolled on his bell.

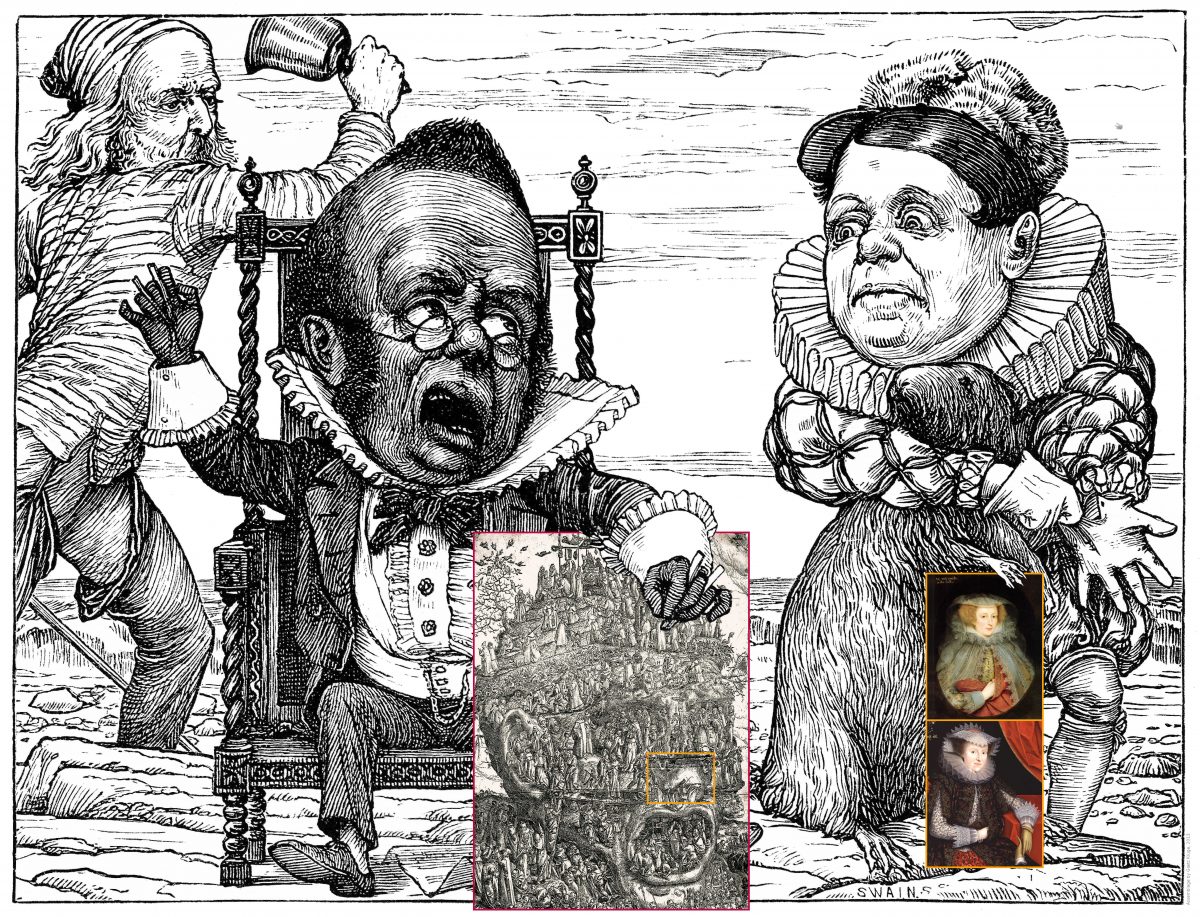

※ Lewis Carroll (text) and Henry Holiday (illustration)

※ Lewis Carroll (text) and Henry Holiday (illustration)

※ Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder

※ Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger

※ On Borrowing

2022-05-31 (my 5696×4325 assemblage: 2013)

update: 2022-11-08

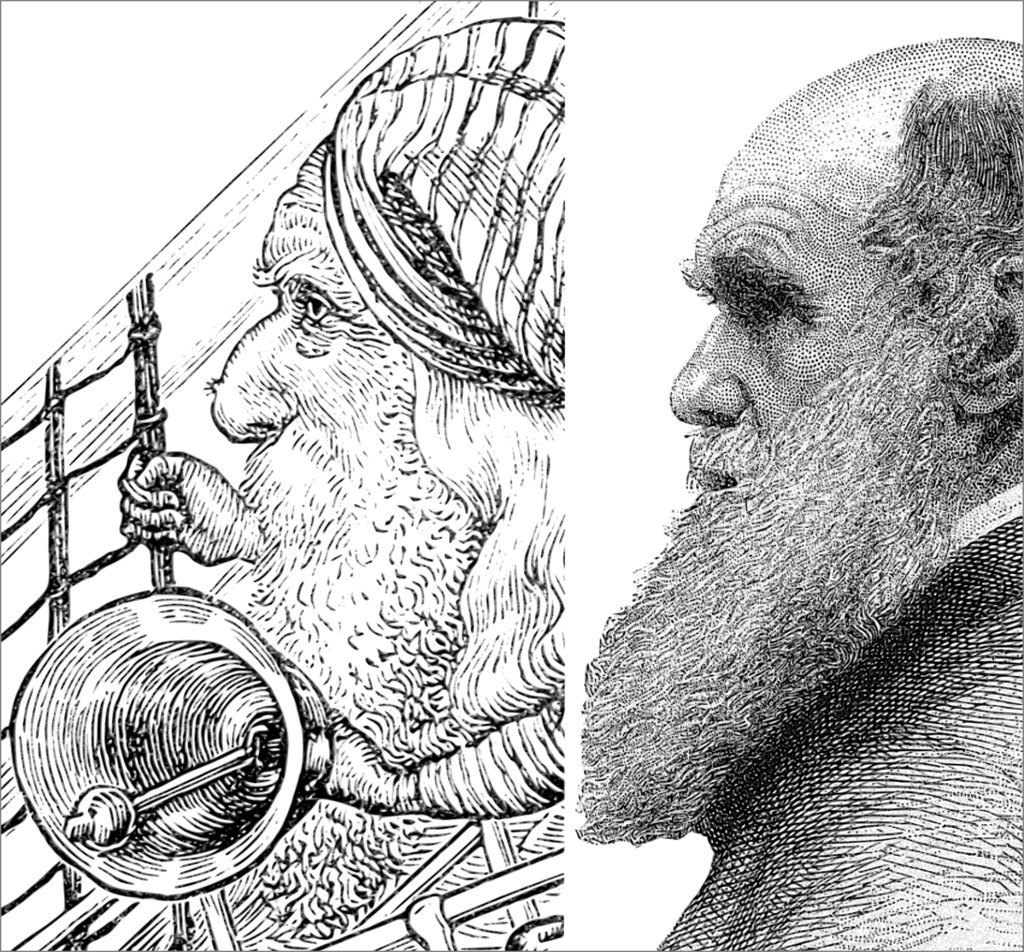

Charles Darwin

The Bellman and Charles Darwin.

As for Darwin’s beard see also: Charles Darwin’s wild whiskers in From Charles Darwin’s beard to George Eliot’s right hand: 4 famous Victorian bodily quirks

As for Darwin’s beard see also: Charles Darwin’s wild whiskers in From Charles Darwin’s beard to George Eliot’s right hand: 4 famous Victorian bodily quirks

In an early preparatory draft, the Bellman had a quite different face. Henry Holiday later used that face (an Oxford colleague?) in another illustration.

2017-08-27, updated: 2022-10-31

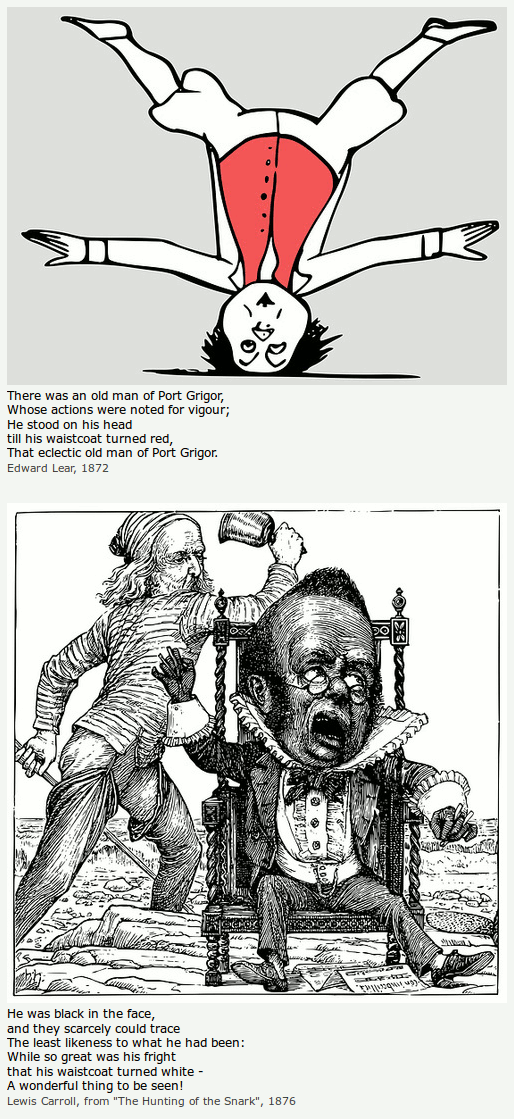

Waistcoat Poetry

There was an old man of Port Grigor,

Whose actions were noted for vigour;

He stood on his head

till his waistcoat turned red,

That eclectic old man of Port Grigor.

He was black in the face,

and they scarcely could trace

The least likeness to what he had been:

While so great was his fright

that his waistcoat turned white –

A wonderful thing to be seen!

Lewis Carroll, from “The Hunting of the Snark”, 1876

Martin Gardner annotated (MG058) to The Hunting of the Snark that Elizabeth Sewell pointed out in The Field of Nonsense (1952) that a line in Carroll’s poem has a similarity to a line in a limerick by Edward Lear.

Martin Gardner annotated (MG058) to The Hunting of the Snark that Elizabeth Sewell pointed out in The Field of Nonsense (1952) that a line in Carroll’s poem has a similarity to a line in a limerick by Edward Lear.

See also:

- Alex Dalenberg (2014-04-02): A Sense for Nonsense: From Edward Lear to Lewis Carroll to Dr. Seuss

- Louise Schweitzer (Louise Dumas), One Wild Flower, Ph.D. thesis, 2012 (Goodreads)

- Wikipedia

- … While so great was his fright …

- On Borrowing

- Bandersnatched Baker 6000×6000

In The Field of Nonsense (I use a 2015 reprint), Elizabeth Sewell compared Carroll’s waistcoat stanza and Lears’s waistcoat limerick while taking a safe distance to considering “mutual plagiarism” by stating that “there is no evidence that either man was familiar with the other’s work”, adding that “the likeness do not in any case suggest borrowings…” (p. 9). However, Carroll/Dodgson knew Lear’s work (Marco Graziosi), and borrowing isn’t necessarily evil.

2017-09-11, update: 2022-10-24

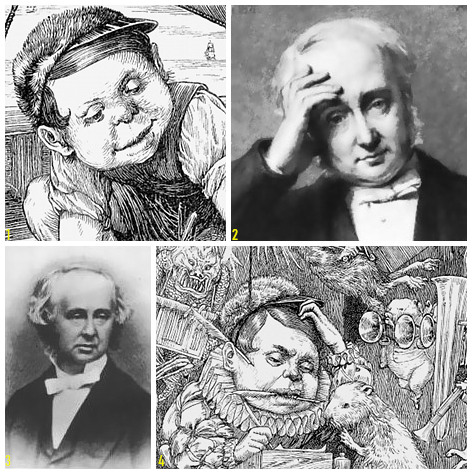

Benjamin Jowett

Image sources: (1, 4) Henry Holiday, (2) probably by The Autotype Company, after Désiré François Laugée, (3) from cover of Benjamin Jowett and the Christian Religion by Peter Hinchliff.

[…]

Need I rehearse the history of Jowett?

I need not, Senior Censor, for you know it.

That was the Board Hebdomadal, and oh!

Who would be free, themselves must strike the blow!

[…]

C.L. Dodgson, from Notes by an Oxford chiel (1874)

For comparison (inspired by Dodgson?):

First come I. My name is J-W-TT.

There’s no knowledge but I know it.

I am Master of this College,

What I don’t know isn’t knowledge.

Source: The Balliol Rhymes (written in the 1880s), ed. W. G. Hiscock, 2nd edn. (1939; Oxford: printed for the editor, 1955): 1-25. PN 6110 C7H5 Robarts Library (Wikipedia: In 1880, seven undergraduates of Balliol published 40 quatrains of doggerel lampooning various members of the college under the title The Masque of B–ll––l, now better known as The Balliol Masque, in a format that came to be called the “Balliol rhyme“.The college authorities suppressed the publication fiercely.)

I suggest that The Barrister’s Dream in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark is about E.B. Pusey’s attempt to trial Jowett for heresy at the Vice-Chancellor’s Court for unpaid bills for heresy. According to Karen Gardiner (see p. 55 below), the trial began on 1863-03-20. The judge was an academic common lawyer. Jowett’s lawyer objected to the formally civilian court being turned into something like a court of common law, which had no jurisdiction in spiritual matters. The Punch (the anonymous author Dodgson?) called it the “small debts and heresies court“. The judge disagreed, provided it could be shown that Jowett had been guilty of breaking any of the university statues. As this could not be shown, the case was dismissed. Thus, the trial was a mess like the trial in the Barrister’s dream.

“In the matter of Treason the pig would appear

To have aided, but scarcely abetted:

While the charge of Insolvency fails, it is clear,

If you grant the plea ‘never indebted.’

See also:

※ Lewis Carroll, «Take care of the sense and the sounds will take care of themselves.» in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

※ Lewis Carroll, «The New Method of Evaluation as applied to π», 1865

※ John Tufail, The Jowett Controversy, 2010 (document creation date)

※ Karen Gardiner, Escaping Justice in Wonderland (An adaption of a paper given at the Glasgow International Fantasy Conference 2018), published in The Carrollian No. 33 p. 47 ~ 60, March 2020 (abstract, 2018).

※ Essays and Reviews

2018-05-03, update: 2022-10-17

Pursuit of Happiness

Part of C.L. Dodgson’s (Lewis Carroll’s) Snark marketing was to claim that he doesn’t know the meaning of The Hunting of the Snark. But there was a meaning which he liked

To Mary Barber

The Chestnuts, Guildford

January 12, 1897My dear May,

In answer to your question, “What did you mean the Snark was?” will you tell your friend that I meant that the Snark was a Boojum. I trust that she and you will now feel quite satisfied and happy.

To the best of my recollection, I had no other meaning in my mind, when I wrote it: but people have since tried to find the meanings in it. The one I like best (which I think is partly my own) is that it may be taken as an Allegory for the Pursuit of Happiness. The characteristic “ambition” works well into this theory—and also its fondness for bathing-machines, as indicating that the pursuer of happiness, when he has exhausted all other devices, betakes himself, as a last and desperate resource, to some such wretched watering-place as Eastbourne, and hopes to find, in the tedious and depressing society of the daughters of mistresses of boarding-schools, the happiness he has failed to find elsewhere.

With every good wish for your happiness, and for the priceless boon of health also, I am

Always affectionately yours,

C.L. Dodgson

To all meaning deniers in a nutshell: There is a meaning which partly is Carroll’s own meaning. Therefore The Hunting of the Snark has at least one meaning.

About “May”vs. “Mary”: In The Selected Letters of Lewis Carroll (1982, edited by Morton Cohen) and in all copies of this letter in the internet, C.L. Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) is being quoted as having addressed Mary Barber with “My dear May”, not with “My dear Mary”. I learned that “My dear May” is correct: Quora | Xwitter

2018-04-29, update: 2022-07-16