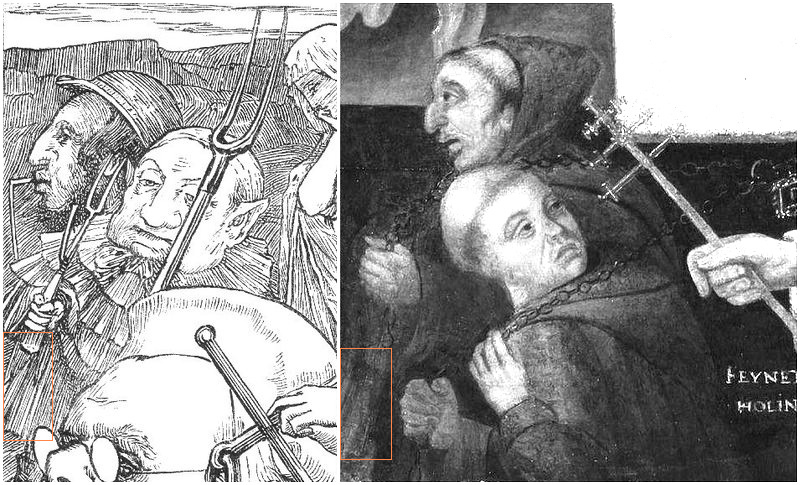

Unknown artist: King Edward VI and the Pope, an Allegory of Reformation, (NPG 4165). The 16th century anti-papal propaganda painting shows Henry VIII on his deathbed and his son Edward VI on the throne. Iconoclasm is depicted in the window-like inset.

Until 1874, the painting was the property of Thomas Green, Esq., of Ipswich and Upper Wimpole Street, a collection ‘Formed by himself and his Family during the last Century and early Part of the present Century’ (Roy C. Strong: Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, 1969, p.345). It was sold by Christie’s 20 March 1874 (lot 9) to an unknown buyer. I am curious about who might have purchased that painting.

Present location: National Portrait Gallery, London

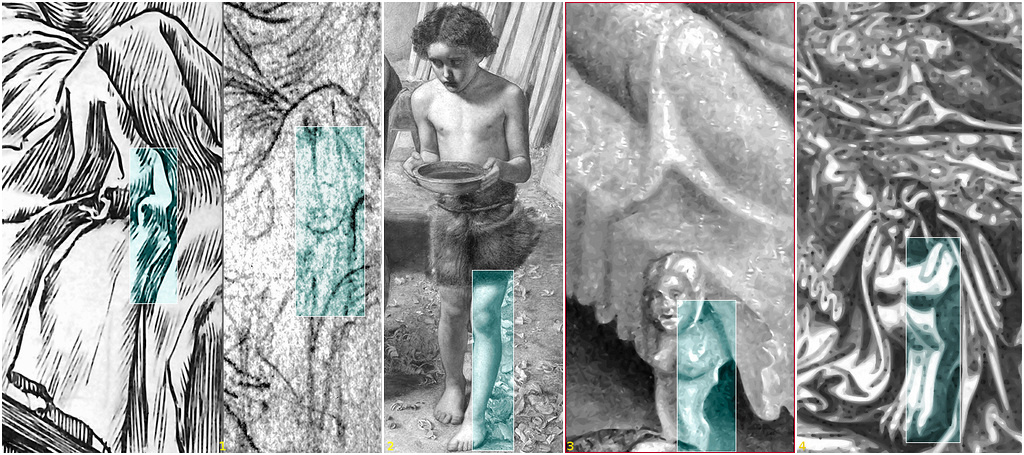

Retinex filtered version of an image from commons.wikimedia.org

Retinex filtered version of an image from commons.wikimedia.org

Edward VI and the Pope: An Allegory of the Reformation. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Inscribed on open book, centre left: “THE WORDE OF THE LORD ENDURETH FOR EVER”; on ribbons of pope’s tiara: “IDOLATRY” and “SUPERSTIC[ION]”; on pope’s chest: “ALL FLESHE IS GRASSE” (‘All flesh is grass,’ from Isaiah 40:6, meaning the body is ephemeral); lower left in the golden frame: “POPS” and “FEYNED HOLINE[SS]”.

The painting represents the handing over of power from Henry VIII to his son Edward VI. Henry lies in bed, and Edward sits on a dais beneath a cloth of state, with a book at his feet containing a text from Isaiah, which falls onto the slumped figure of a pope. The pope points a triple cross towards two monks, lower left, who pull on chains attached to Edward’s dais. Standing to Edward’s side is a figure identified as his uncle, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector. Other figures on the right represent Edward’s Privy Council and include the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer (in white), the Lord Privy Seal John Russell (grey beard), and William Paget (forked beard), the Comptroller of the King’s Household. At top right is a picture of iconoclasm, the smashing of idols, an activity approved of by Cranmer and many religious reformers.

The scholarship on this painting is conflicted. It was once taken for granted that the painting was contemporary with the succession of Edward VI in 1547. Dr Margaret Aston, in The King’s Bedpost, a book devoted to this painting, has claimed instead that the work could not have been painted before the late 1560s. She bases her theory on the similarities between the sphinx bedpost (foot of Henry’s bed) and between the column in the iconoclastic scene and those in two engravings of pictures by Maerten van Heemskerk produced between 1564 and 1569. Roy Strong has accepted Aston’s redating of the picture but regards many of her views on the painting’s significance as conjectural. Jennifer Loach has challenged Aston’s reading of the picture, disputing her identification of some of the figures (she accepts the ones mentioned above, however), and believes that the painting was a piece of contemporary propaganda, created during Edward VI’s reign. (References: Margaret Aston, The King’s Bedpost. Reformation and Iconography in a Tudor Group Portrait, Cambridge, 1993; Roy Strong, The Tudor and Stuart Monarchy. Pageantry, Painting, and Iconography, Woodbridge (UK), 1995; Jennifer Loach, Edward VI, Yale University Press, 1999.)

Source: wikimedia

Links:

- Related pages in this blog

- Margaret Aston, The King’s Bedpost: Reformation and Iconography in a Tudor Group Portrait, 1994

- King Edward VI and the Pope and Elizabeth I: Drawing Parallels in Tudor Group Portraits and Texts, Chelsea Swales, 2016

- The Final Days of Henry VIII

- Chelsea Swales, King Edward VI and the Pope and Elizabeth I: Drawing Parallels in Tudor Group Portraits and Texts

- Jacqueline Callcut, The King, the Book and the Painting

- Alex David, page on the Edward&Pope painting in the tumble site British Royal Portraits

- Popes: Clemens VII (1523-1534) and Paul III (1534-1549)

See #3 (second from right, mirrored detail) as part of a chain of allusions:

Back to the comparison based on Margaret Aston’s The King’s Bedpost:

2017-11-25, update: 2022-08-10