How can we recognize a Snark? The Bellman explains it (🎶🎶🎶): A Snark is not necessarily evil, but once it turns into a Boojum, you are in trouble.

“Come, listen, my men, while I tell you again

The five unmistakable marks

By which you may know, wheresoever you go,

The warranted genuine Snarks.

“Let us take them in order.

- The first is the taste,

Which is meagre and hollow, but crisp:

Like a coat that is rather too tight in the waist,

With a flavour of Will-o’-the-wisp. - “Its habit of getting up late you’ll agree

That it carries too far, when I say

That it frequently breakfasts at five-o’clock tea,

And dines on the following day. - “The third is its slowness in taking a jest.

Should you happen to venture on one,

It will sigh like a thing that is deeply distressed:

And it always looks grave at a pun. - “The fourth is its fondness for bathing-machines,

Which it constantly carries about,

And believes that they add to the beauty of scenes –

A sentiment open to doubt. - “The fifth is ambition.

It next will be right

To describe each particular batch:

Distinguishing

※ those that have feathers, and bite,

※ And those that have whiskers, and scratch.

“For, although common Snarks do no manner of harm,

Yet, I feel it my duty to say,

Some are Boojums –” The Bellman broke of in alarm,

For the Baker had fainted away.

…

“He remarked to me then,” said that mildest of men,

“ ‘If your Snark be a Snark, that is right:

Fetch it home by all means – you may serve it with greens,

And it’s handy for striking a light.

“ ‘You may seek it with thimbles—and seek it with care;

You may hunt it with forks and hope;

You may threaten its life with a railway-share;

You may charm it with smiles and soap –’ ”

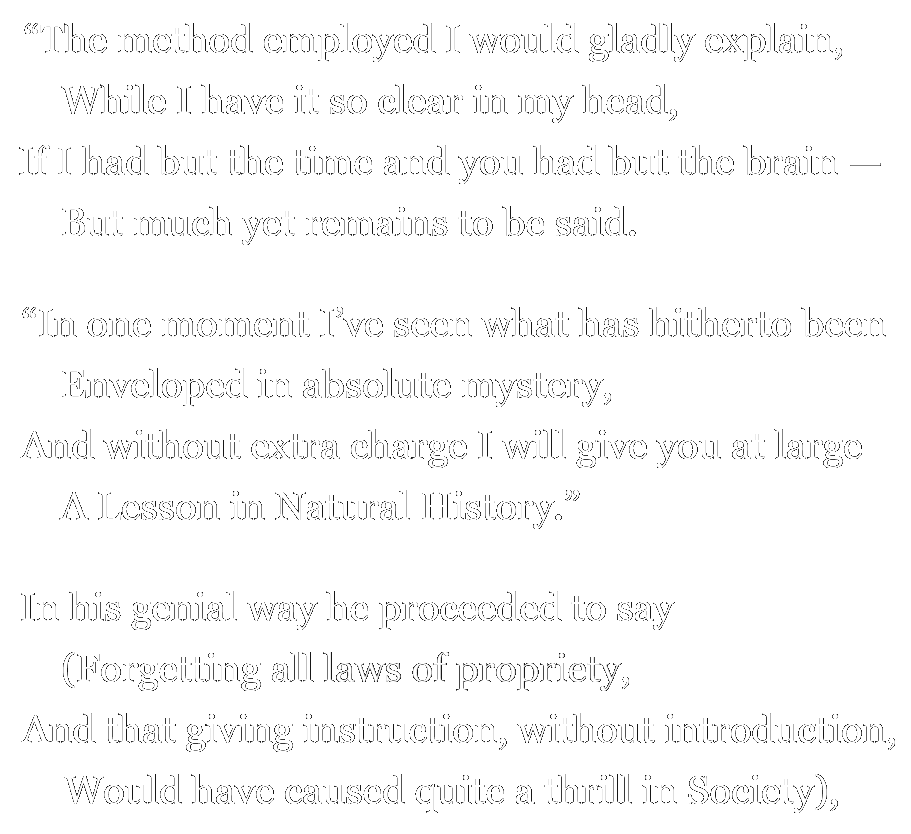

(“That’s exactly the method,” the Bellman bold

In a hasty parenthesis cried,

“That’s exactly the way I have always been told

That the capture of Snarks should be tried!”)

“ ‘But oh, beamish nephew, beware of the day,

If your Snark be a Boojum! For then

You will softly and suddenly vanish away,

And never be met with again!’

…

“I engage with the Snark — every night after dark —

In a dreamy delirious fight:

I serve it with greens in those shadowy scenes,

And I use it for striking a light:

“But if ever I meet with a Boojum, that day,

In a moment (of this I am sure),

I shall softly and suddenly vanish away —

And the notion I cannot endure!”

Important: The descriptions above are opinions of the Bellman, the Baker and the Baker’s Uncle. The views of these characters are not necessarily Lewis Carroll’s views: “I do not hold myself responsible for any of the opinions expressed by the characters in my book.” (Lewis Carroll, Sylvie and Bruno Concluded). However, the “delirious fight” “every night after dark” could be a reference to the author’s own “mental troubles“.

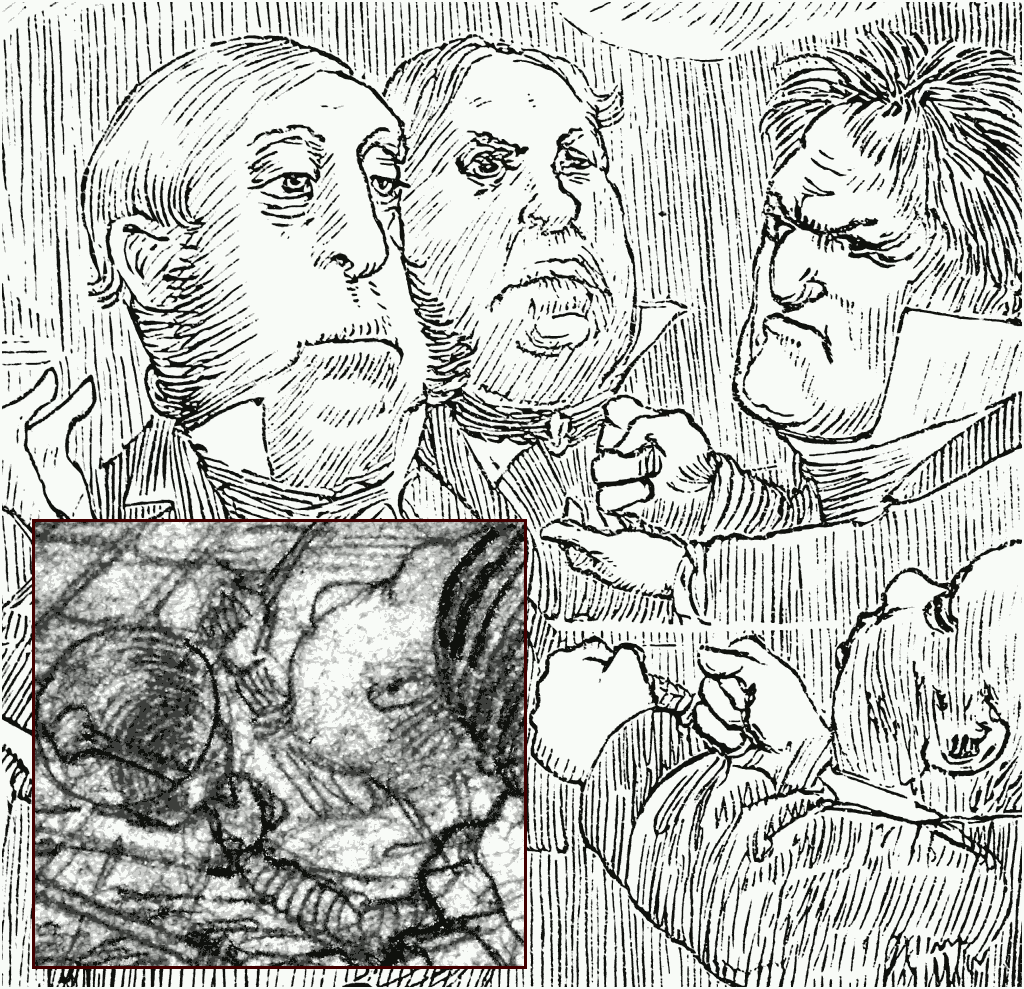

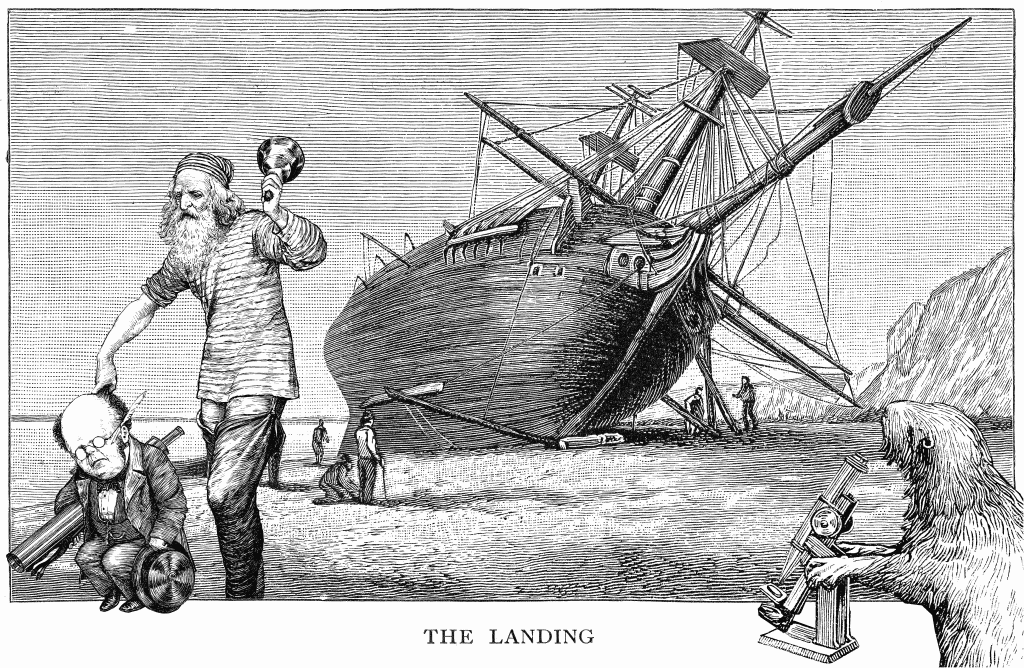

Among the forks mentioned above (used to hunt the Snark and carried by this landing crew of a naval expedition) is a tuning fork (held by the Banker).

On his naval expedition with the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin used a tuning-fork to let spiders dance, and for dissection (don’t tell the spiders) he used lace-needles together with his microscope (like the one carried by the beaver).

2017-09-18, edited 2025-10-30

Among the

Among the

Jabberwocky, Confounded

Jabberwocky, Confounded Muppets

Muppets There are also

There are also

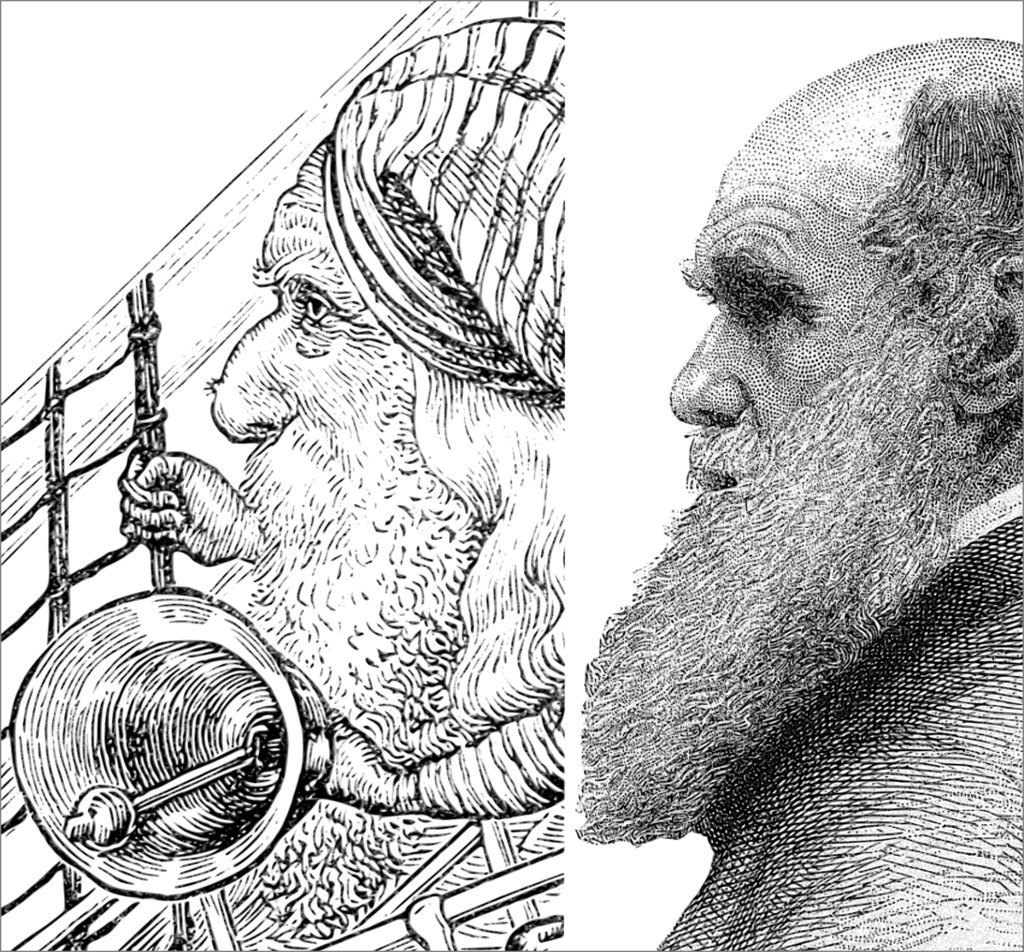

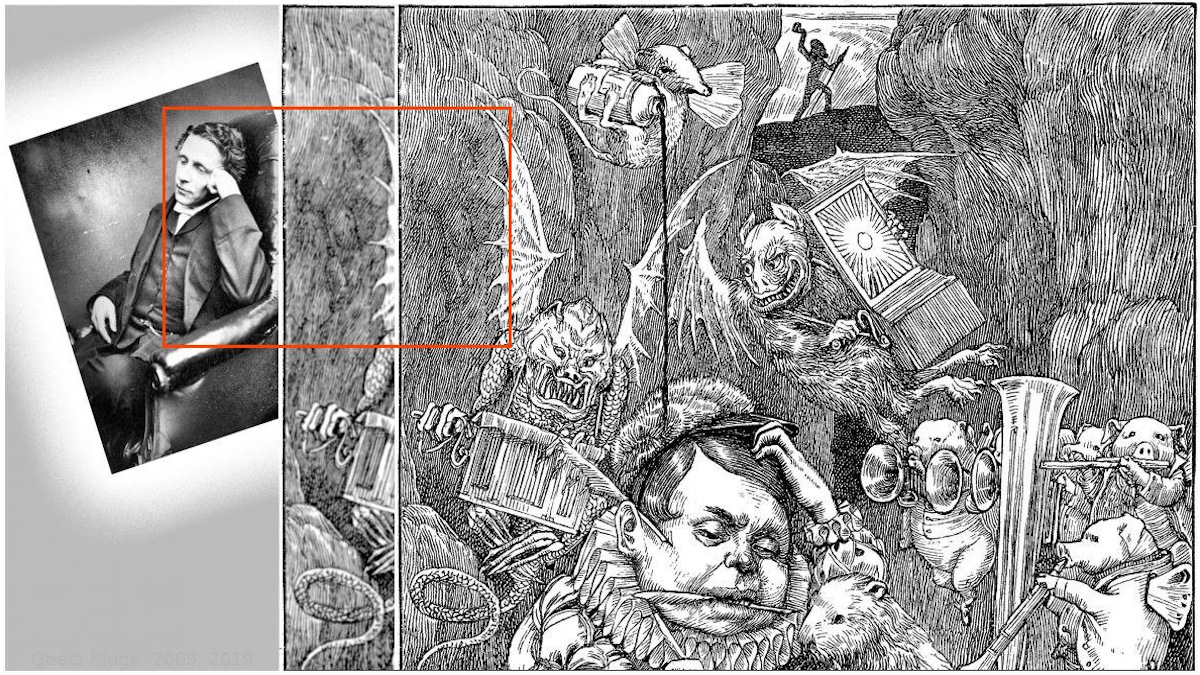

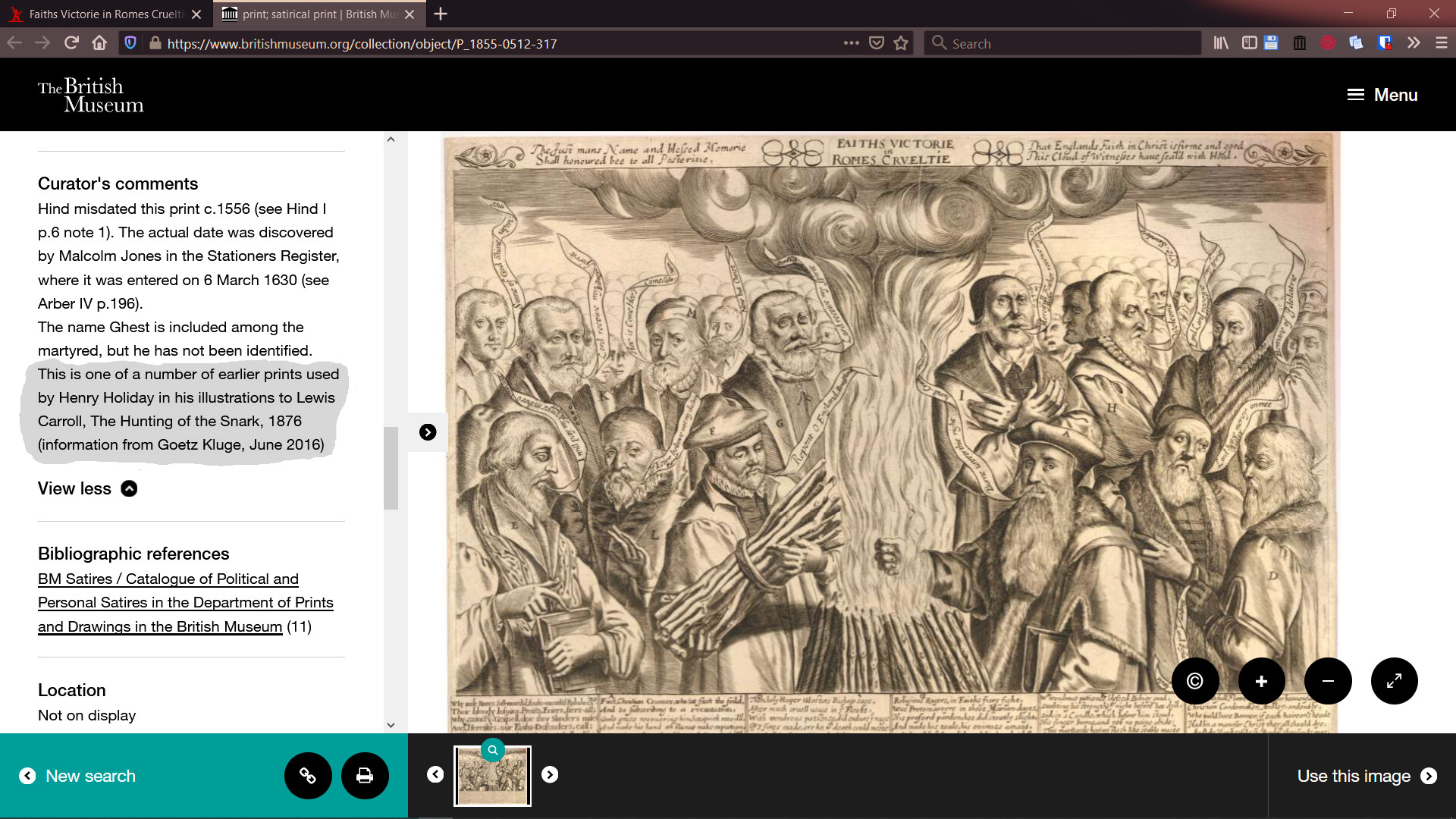

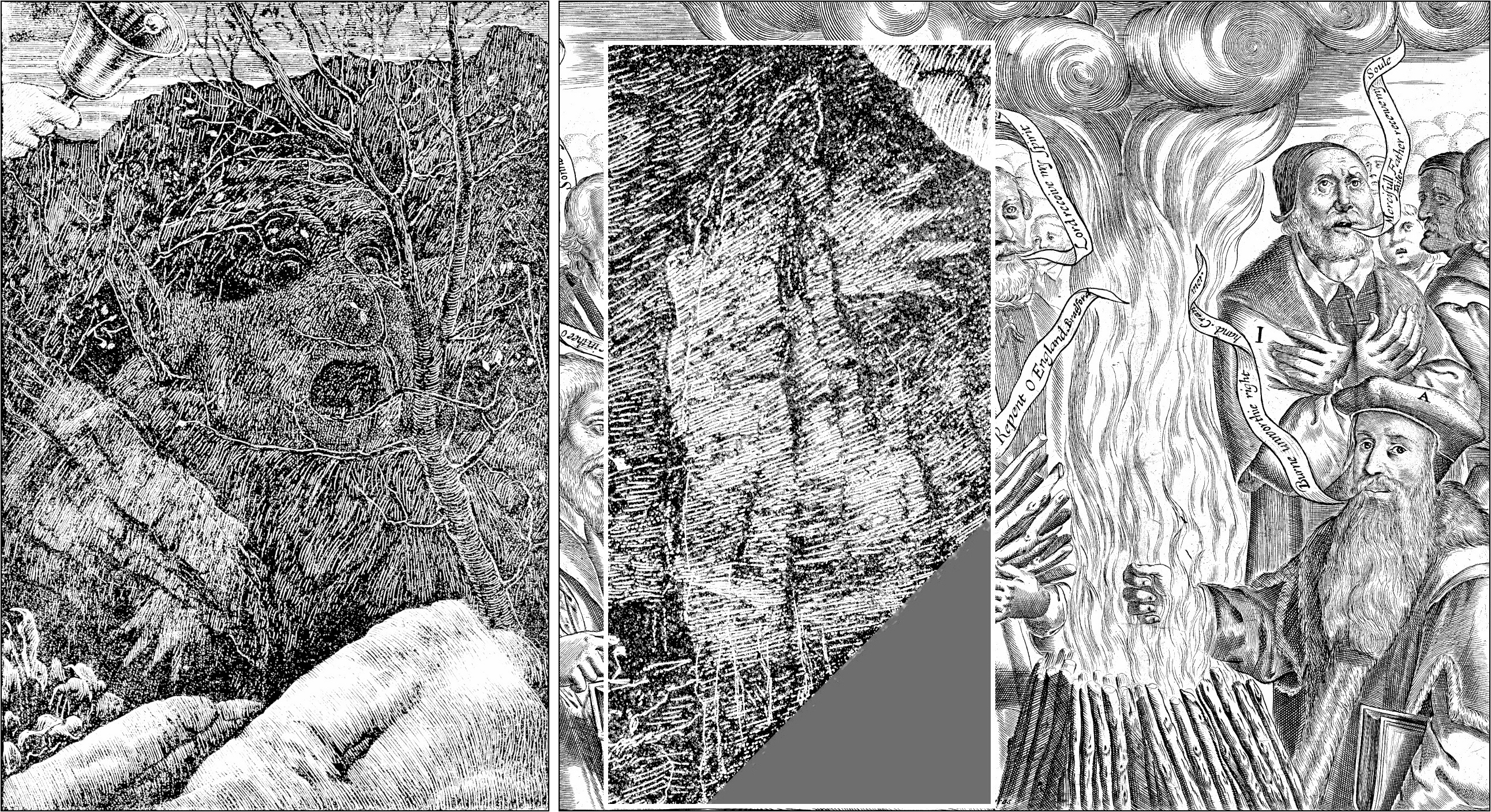

Before my Snark hunt started in December 2008, I mainly focused on Henry Holiday’s

Before my Snark hunt started in December 2008, I mainly focused on Henry Holiday’s

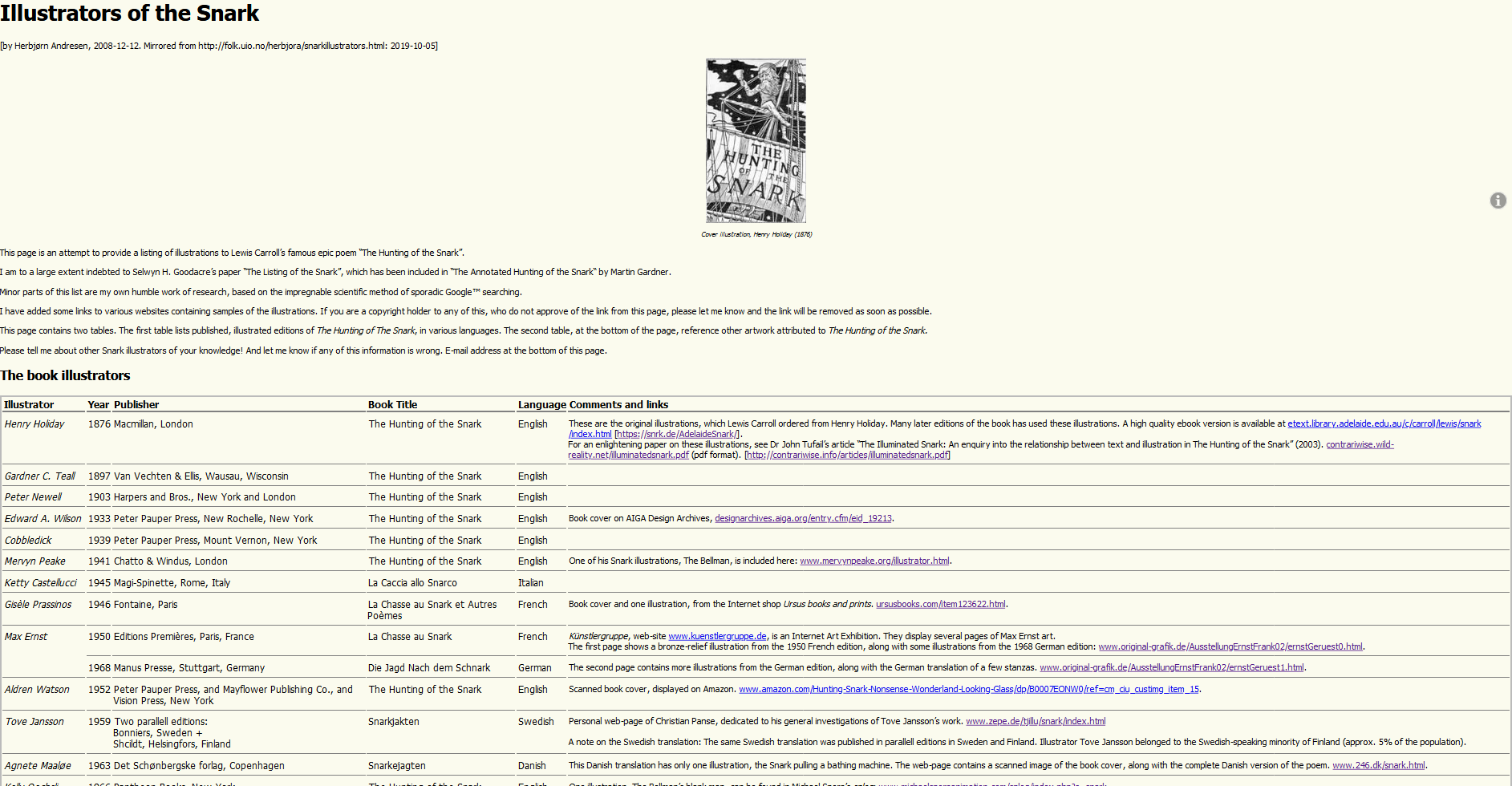

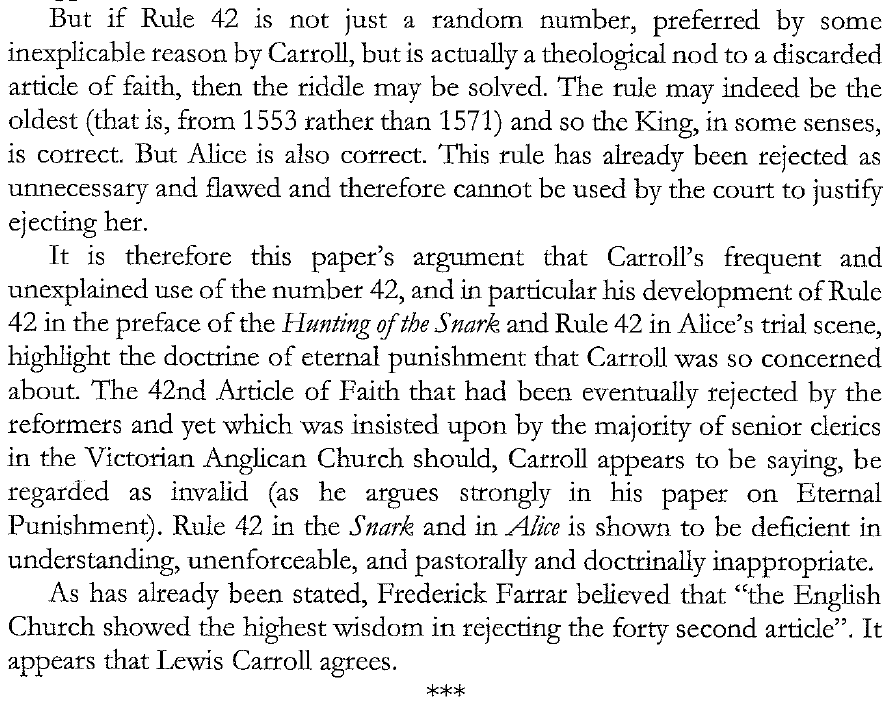

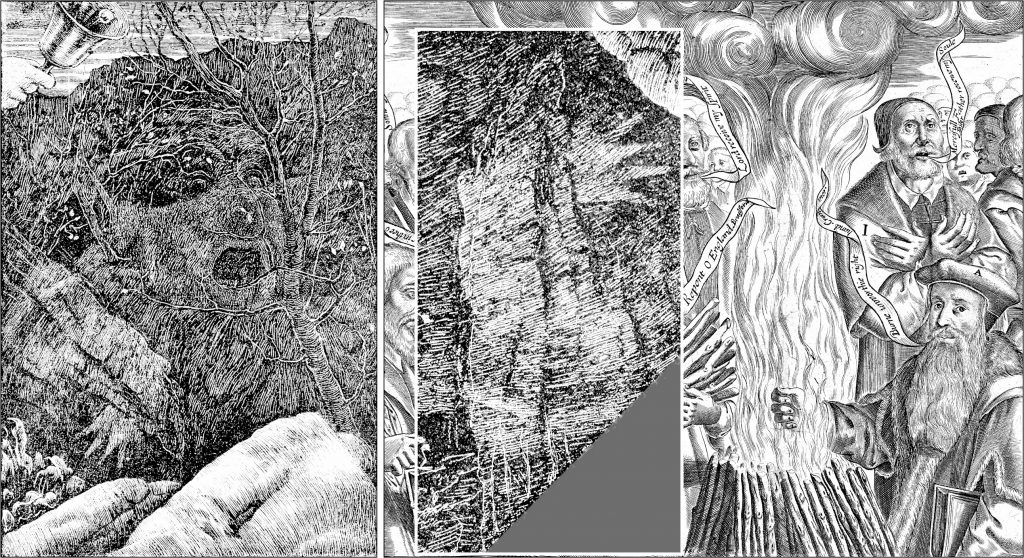

I think that Dodgson addressed conflicts within the Curch of England and the related legal battles (see

I think that Dodgson addressed conflicts within the Curch of England and the related legal battles (see  As for the looks, Richard Bethell, 1st Baron Westbury could be another candidate for Holiday’s reference.

As for the looks, Richard Bethell, 1st Baron Westbury could be another candidate for Holiday’s reference.

It was quite probably Henry Holiday’s

It was quite probably Henry Holiday’s

About me:

About me: