Perhaps I may venture for a moment to use a more serious tone, and to point out that there are mental troubles, much worse than mere worry, for which an absorbing object of thought may serve as a remedy.

- There are sceptical thoughts, which seem for the moment to uproot the firmest faith;

- there are blasphemous thoughts, which dart unbidden into the most reverent souls;

- there are unholy thoughts, which torture with their hateful presence the fancy that would fain be pure.

Against all these some real mental work is a most helpful ally. That “unclean spirit” of the parable, who brought back with him seven others more wicked than himself, only did so because he found the chamber “swept and garnished,” and its owner sitting with folded hands. Had he found it all alive with the “busy hum” of active work, there would have been scant welcome for him and his seven!

(Charles Lutwidge Dodgson: Pillow Problems and A Tangled Tale, 1885, p. XV;

see also: Life & Letters. Bulletpoints not by Dodgson.)

As any human, Carroll/Dodgson was battling with all kind of temptations. As we know, speculations about possible temptations in his private life keep feeding the pop culture Carroll debate since the 1930s. The controversy is marginalizing the religious conflicts which Dodgson, the Deacon, was struggling with. I think that one of these serious conflicts was Charles Darwin’s challenge to fundamental religious beliefs. The discoveries of Darwin and other researchers surely had (and still have) the potential to uproot the firmest faith in various religions.

In the title of the book [Pillow-Problems, 2nd edition], the words “sleepless nights” have been replaced by “wakefull hours”.

This last change has been made in order to allay the anxiety of friends, who have written to me to express their sympathy in my broken-down state of health, believing that I am a sufferer of chronic “insomnia”, and that it is a remedy for that exhausting malady that I have recommended mathematical calculation.

The title was not, I fear, wisely chosen; and it certainly was liable to suggest a meaning I did not intend to convey, viz. that my “nights” are often wholly “sleepless”. This is by no means the case: I have never suffered from “insomnia”: and the over-wakeful hours, that I have had to spend at night, have often been simply the result of the over-sleepy hours I have spent during the preceding evening! Nor is it as a remedy for wakefulness that I have suggested mathematical calculation: but as a remedy for the harassing thoughts that are apt to invade a wholly-unoccupied mind.

I believe that an hour of calculation is much better for me than half-an-hour of worry.

(Charles Lutwidge Dodgson: Pillow Problems, preface to the second edition, 1893)

Carroll openly described how he used mental mathematical work to find distraction from “harassing thoughts”.

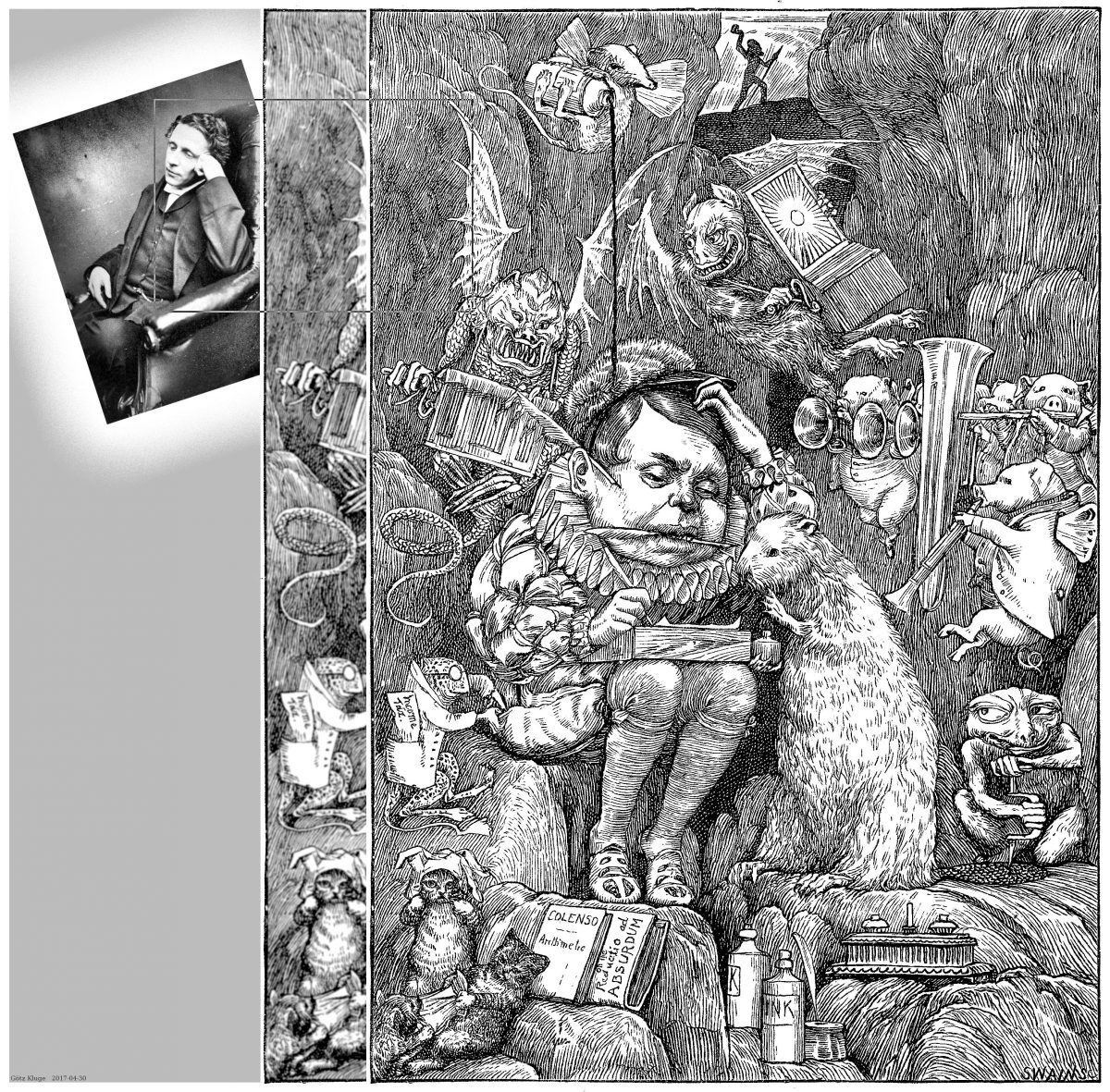

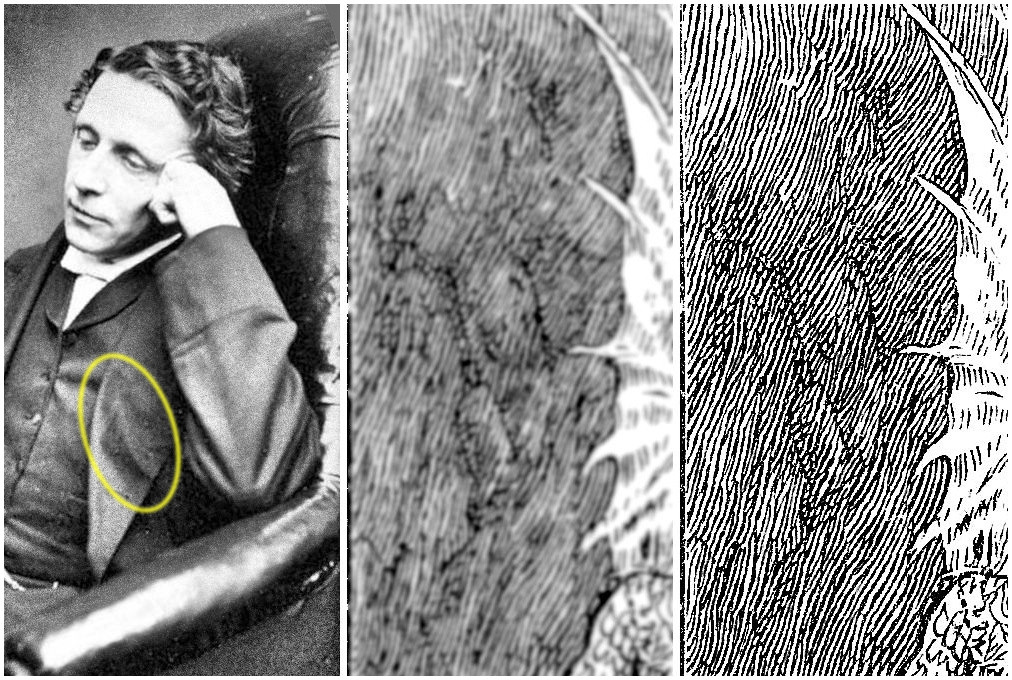

I don’t know to which degree the illustrator Henry Holiday discussed and aligned with Carroll his choice of pictorial references in his illustrations to Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, but there is a pictorial reference to mental troubles: St. Anthony’s temptations (painting by Matthias Grünewald). In one of Holiday’s illustrations you see Colenso’s arithmetic textbook. Like Anthony, also Carroll needed lots of mental work as an distraction from sceptical, blasphemous and unholy thoughts. Anthony probably found help in the scriptures which were sacred to him. Interestingly, the Reverend Dodgson used mathematics to resist the temptations.

I saw Colenso’s math textbook in Holiday’s illustration since many years. Only recently that led me to the assumption (which probably always will be just an assumption) that Holiday might have placed that book into his illustration as a hint to how Carroll used math to keep his brain busy with “some real mental work” as a “most helpful ally” in his battle against the temptations which haunted him.

By the way: Possible references in “The Hunting of the Snark” to St. Anthony and to Darwin had been addressed by Mahendra Singh before I thought about that. Mahendra (who alluded to Matthias Grünewald’s painting himself) and John Tufail were among my most helpful scouts during my own Snark hunt.

2020-06-11, update: 2024-02-05