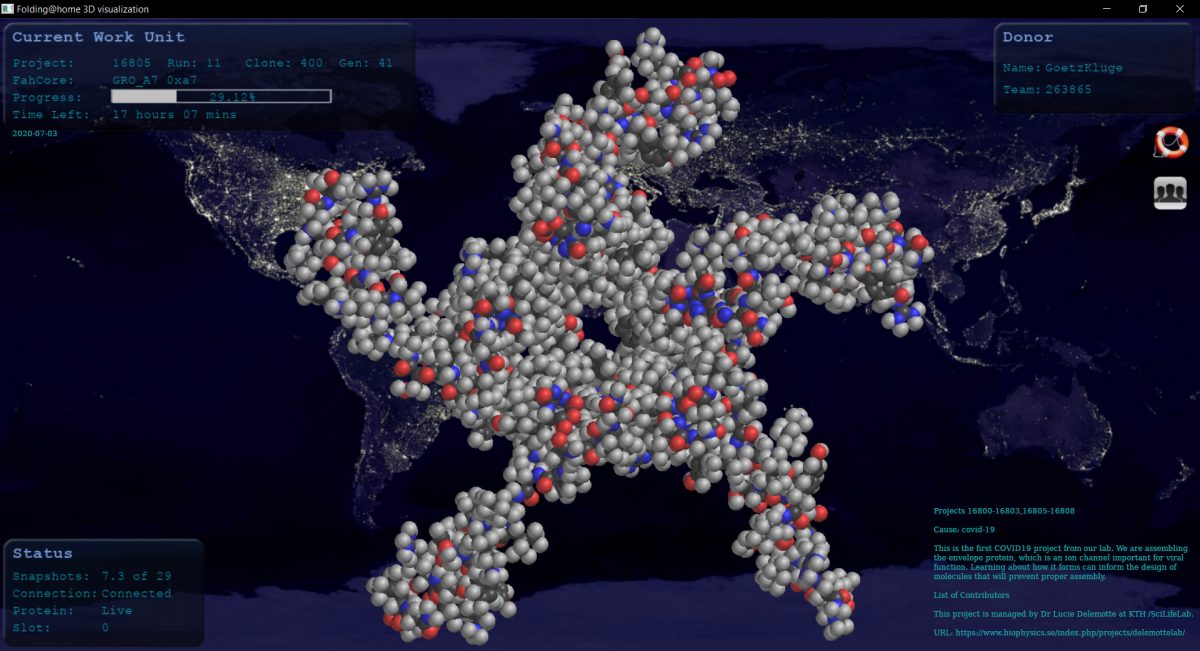

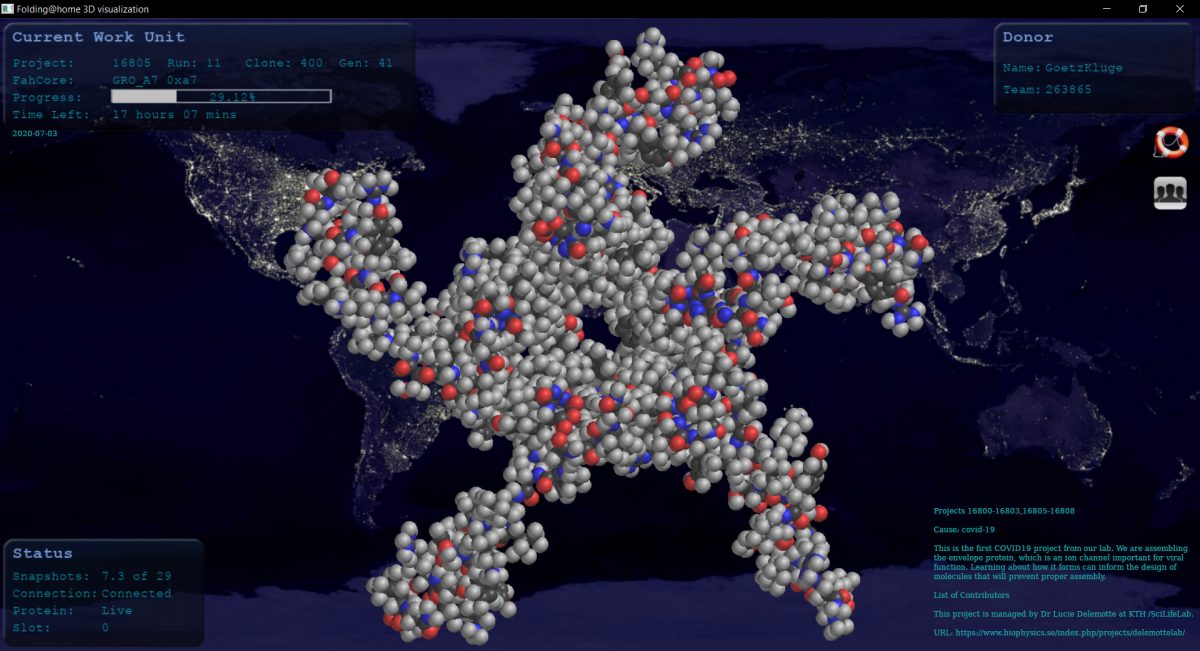

(Project: https://statsclassic.foldingathome.org/project?p=16805. I pasted the text into the image.)

Proteins are not stagnant—they wiggle and fold and unfold to take on numerous shapes. We need to study not only one shape of the viral spike protein, but all the ways the protein wiggles and folds into alternative shapes in order to best understand how it interacts with the ACE2 receptor, so that an antibody can be designed. Low-resolution structures of the SARS-CoV spike protein exist and we know the mutations that differ between SARS-CoV and 2019-nCoV. Given this information, we are uniquely positioned to help model the structure of the 2019-nCoV spike protein and identify sites that can be targeted by a therapeutic antibody. We can build computational models that accomplish this goal, but it takes a lot of computing power.

(Source: https://foldingathome.org/2020/02/27/foldinghome-takes-up-the-fight-against-covid-19-2019-ncov/.)

=== Linux ===

I run folding@home (F@H) on two computers. One operates under MS Windows, the other one is a five years old computer with a Linux operating system. That old computer became very slow due to mitigations against Intel CPU vulnerabilities, so I didn’t use it anymore. But I reactivated it for F@H operated under a bare bone Linux OS. As that computer doesn’t do anything else than folding, I disabled the Intel CPU protection by starting the kernel with “mitigations=off”. (Don’t do that if you use your computer on the network for other tasks besides folding.) It works for kernels at and above version 5.2 and increases the speed (and the F@H point count) significantly. If your computer boots into Linux with GRUB, add mitigations=off to the settings in GRUB_CMDLINE_LINUX_DEFAULT.

=== Teams ===

As part of the “gamification” concept of F@H, your protein model folding computer collect points during folding. (It’s just for fun. Competition is in our genes, F@H plays with that.) You can join teams in order to get to the top in a ranking of teams together with other contributors. By default you are in a Zero team. That’s fine. You don’t have to change anything if you just want to help folding protein models.

Some contributors join teams of organizations (e.g. companies) in order to let these organizations look good. That’s fine too. There are various kind of teams.

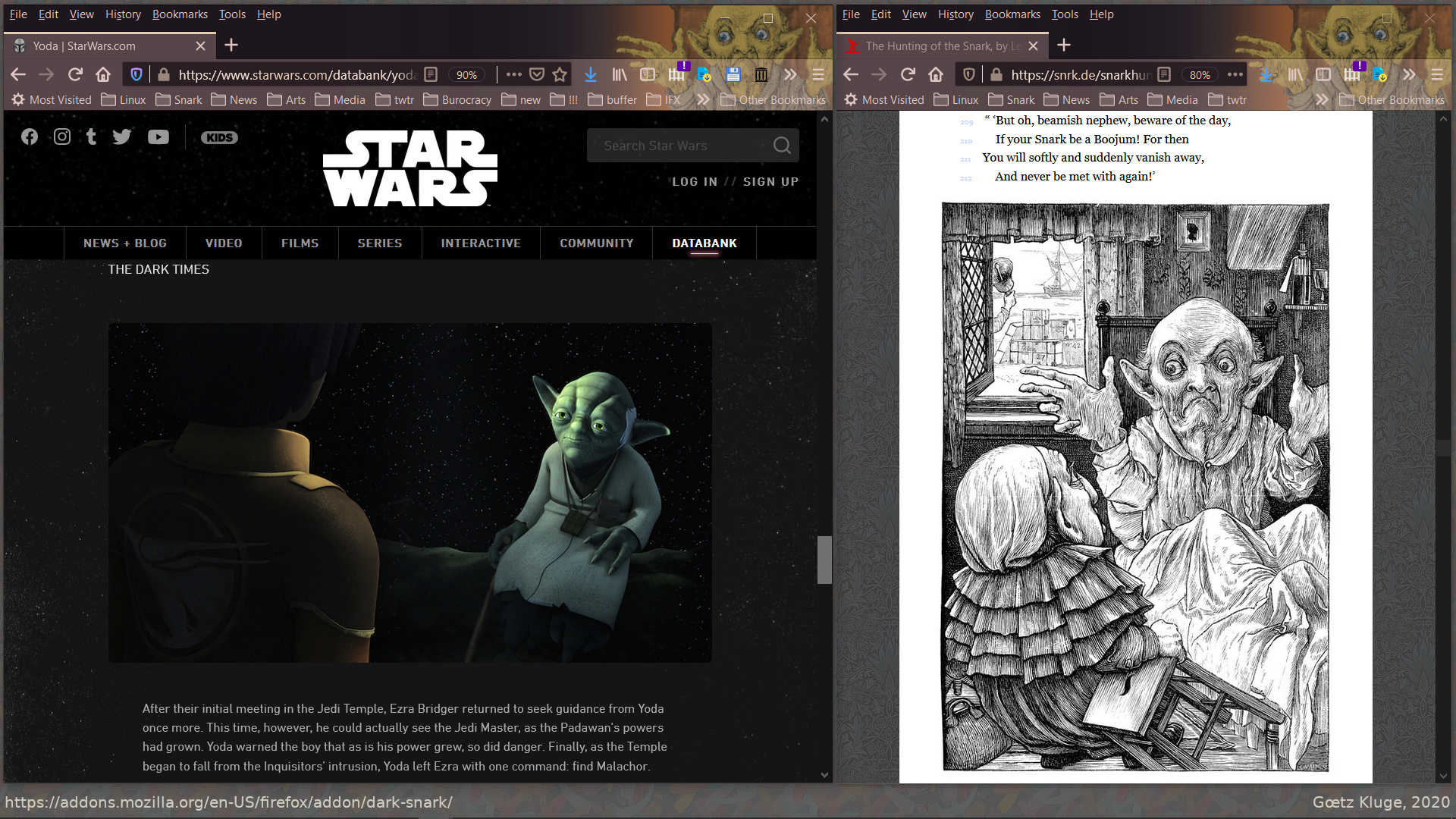

You also easily can create your own team. Due to my obsession, I of course created a The Hunting of the Snark team. (So far it consist of only one member, but as of already is among the top 10% of all teams.)

Curecoin: The top team is the Curecoin team. There you not only get points, you also get some kind of currency. It’s not my thing. One reason for me not to join Curecoin is that the blockchain technology applied would add additional workload to my computer. On the other side, Curecoin isn’t bad either. The Curecoin team has even more points than the Zero team, but much less work units. I think, that is because many contributors in that team run computers with powerful CPUs and GPUs. They get work units done faster than less powerful machines, and the points computation algorithm of F@H acknowledges that. (Thanks to the required number crunching power, blockchain technologies helped the market for graphics cards and GPUs a lot.) Personally I don’t like Curecoin, but as always: Use it if you like it and if you know what you are doing. (Links: Am Rechner nebenher die Welt retten | http://ftreporter.com/all-you-need-to-know-about-Curecoin/)

=== Caveats ===

Depending on the setting (Light/Medium/Full) of FAHcontrol, your computer can get quite hot. The older one of my computers does 24 hours/day folding in a cool room in the basement.  It consumes a power of 26 Watts. The F@H setting is “Full”. It’s a fan-less mini computer, so no tear&wear of an internal fan needs to be considered. But there is an external fan. The computer won’t get damaged by the heat, because it adapts the CPU clock frequency in a way which doesn’t let it get too hot. In winter it won’t reach maximum temperature anyway. But in summer its temperature limits will get tested, even though the ambient temperature will stay below the 50°C maximum. So I added an external fan (14W). My other computer is a laptop computer. I chose the “Light” setting (which means that the GPU will not be used for folding).

It consumes a power of 26 Watts. The F@H setting is “Full”. It’s a fan-less mini computer, so no tear&wear of an internal fan needs to be considered. But there is an external fan. The computer won’t get damaged by the heat, because it adapts the CPU clock frequency in a way which doesn’t let it get too hot. In winter it won’t reach maximum temperature anyway. But in summer its temperature limits will get tested, even though the ambient temperature will stay below the 50°C maximum. So I added an external fan (14W). My other computer is a laptop computer. I chose the “Light” setting (which means that the GPU will not be used for folding).

Super contributors use gaming computers with powerful CPUs and GPUs. And some show off impressive cooling machinery. Those gamers know what they are doing and can run F@H with maximum performance.

=== TeamViewer ===

I remote controlled up to three computers with TeamViewer. I don’t do that anymore. TeamViewer might think that you use that application commercially.

=== Smartphones ===

F@H does not run on smartphones, but there is a project for such devices. The Vodaphone “DreamLab” is a proprietary app. Of course it only runs during charging. I recommend to read the privacy statement.

=== Scams ===

Due to Covid19, F@H became much more popular, so take care not to install malware like fake applications which e.g. steal passwords. Don’t panic, but wherever scams are possible, you’ll have to deal with them. F@H is no exception. Possible scams are no reason not to contribute to F@H, but be aware of scams, e.g. foldingathomeapp.exe is malware! If you want to be on the save side, only install F@H software from foldingathome.org and don’t touch anything else.

=== Snark Hunters ===

There are quite a few Snark related contributors to F@H (2020-08-27)

=== Join ===

You can share computer time too.

F@H Team 263865 | COVID19 | Wikipedia |Twitter | Facebook (en) | Facebook (de)

2020-03-31, update: 2021-10-27

As for the Snark music known to me, Arne Nordheim’s The Return of the Snark – For Trombone And Tape is among my favorites. Nordheim composed this 15 minutes piece in the year 1987. Gaute Vikdal plays the trombone.

As for the Snark music known to me, Arne Nordheim’s The Return of the Snark – For Trombone And Tape is among my favorites. Nordheim composed this 15 minutes piece in the year 1987. Gaute Vikdal plays the trombone.

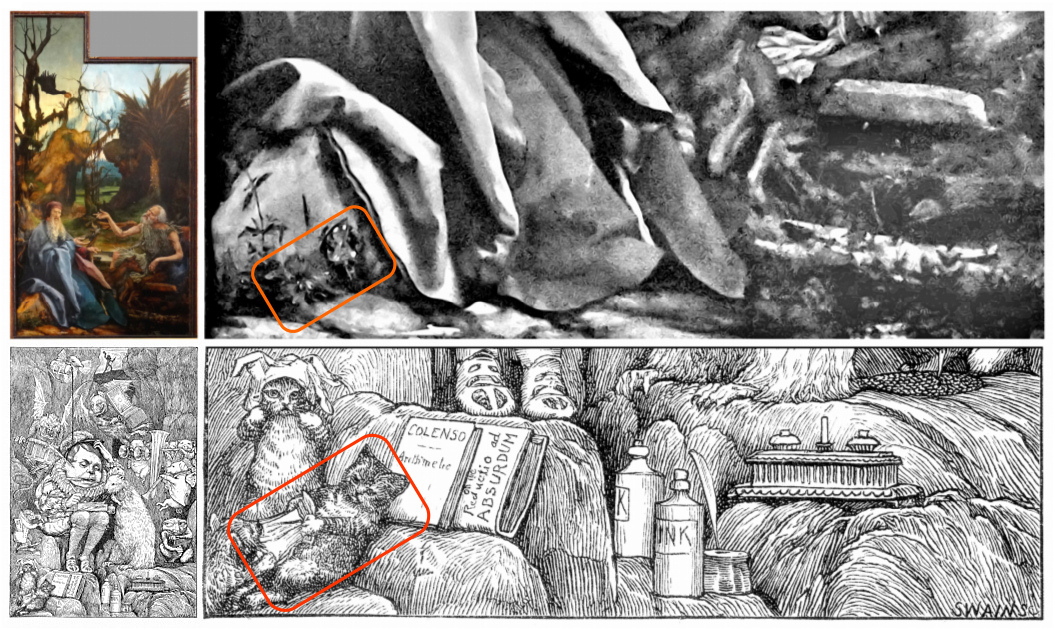

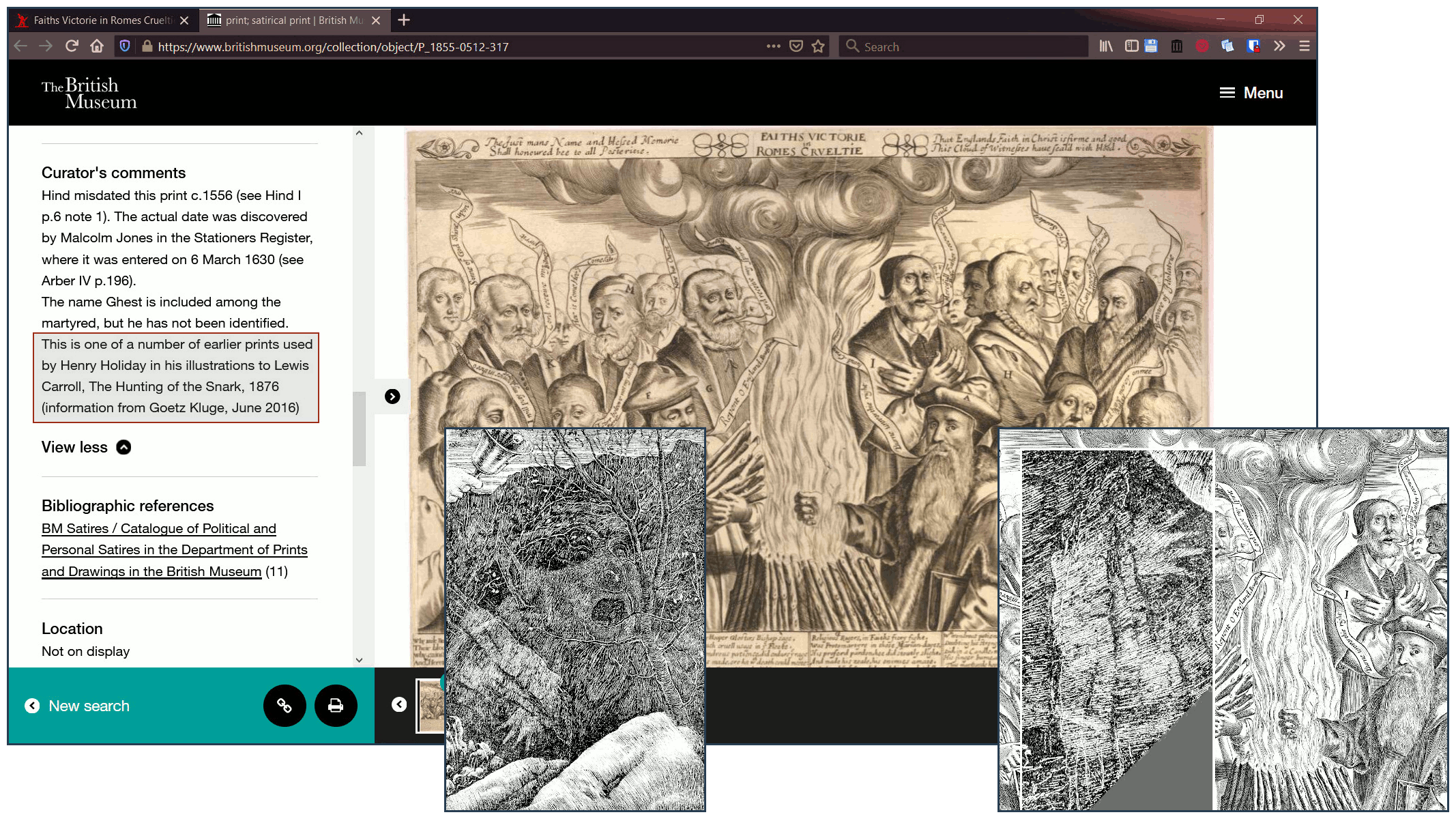

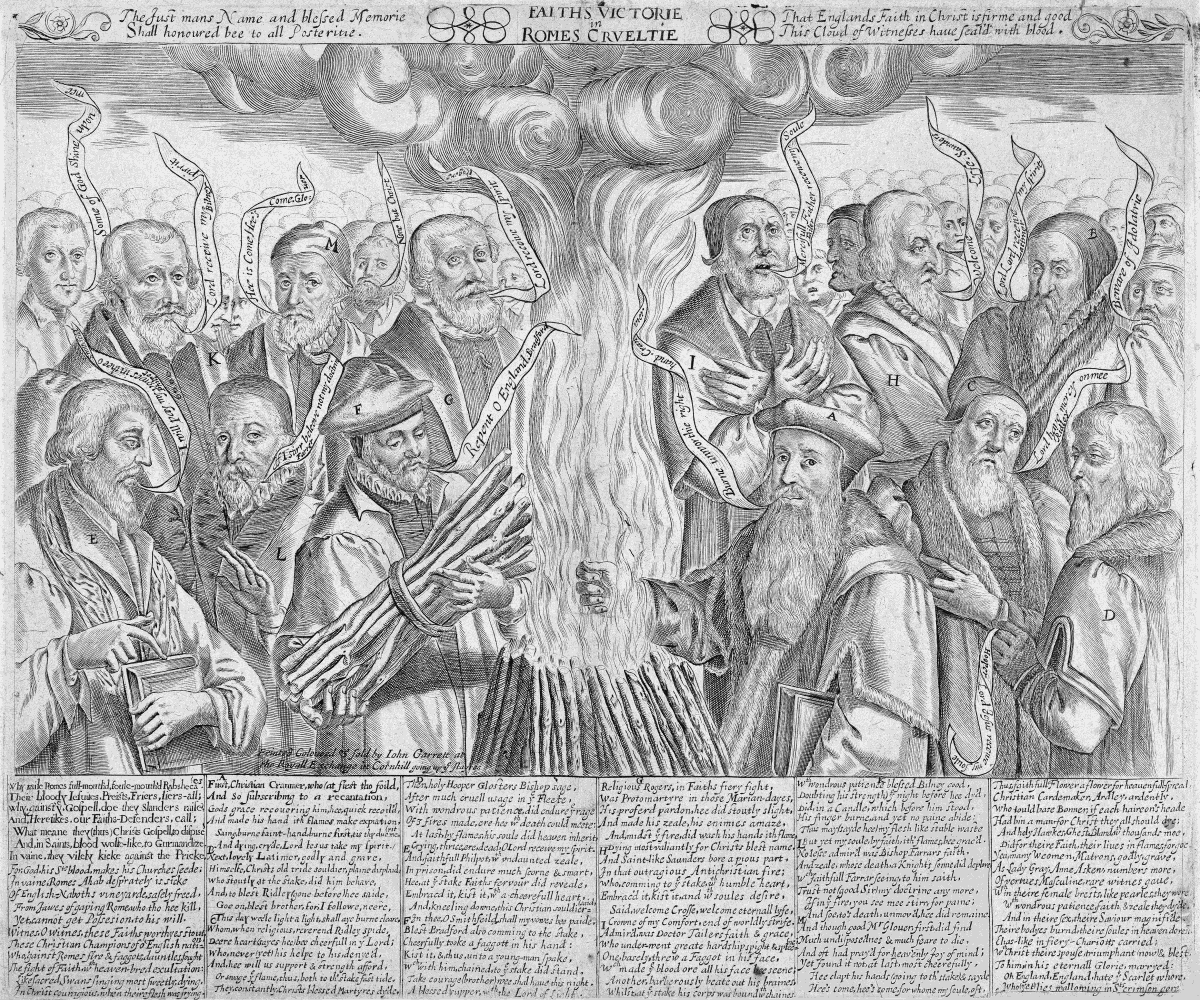

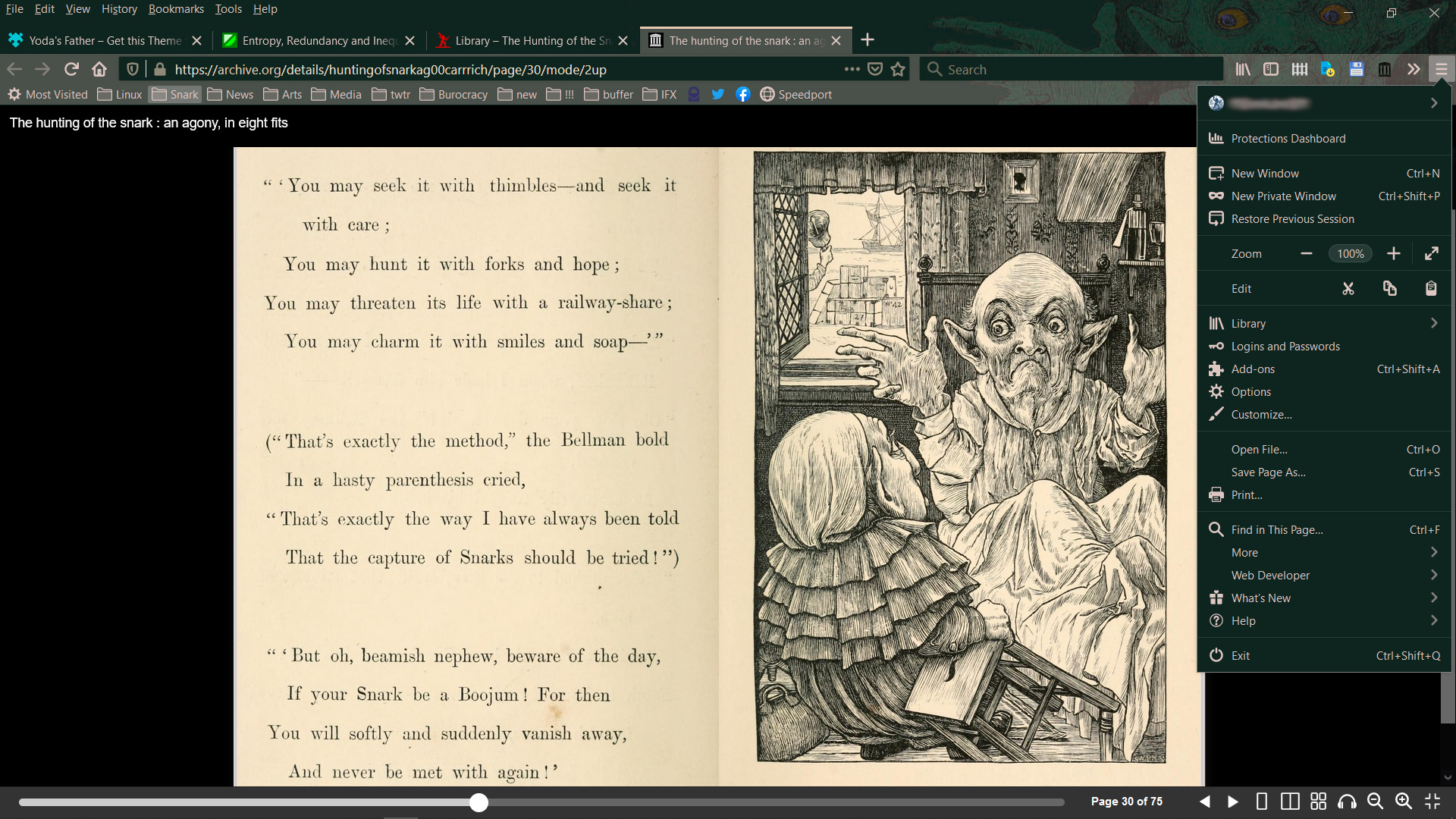

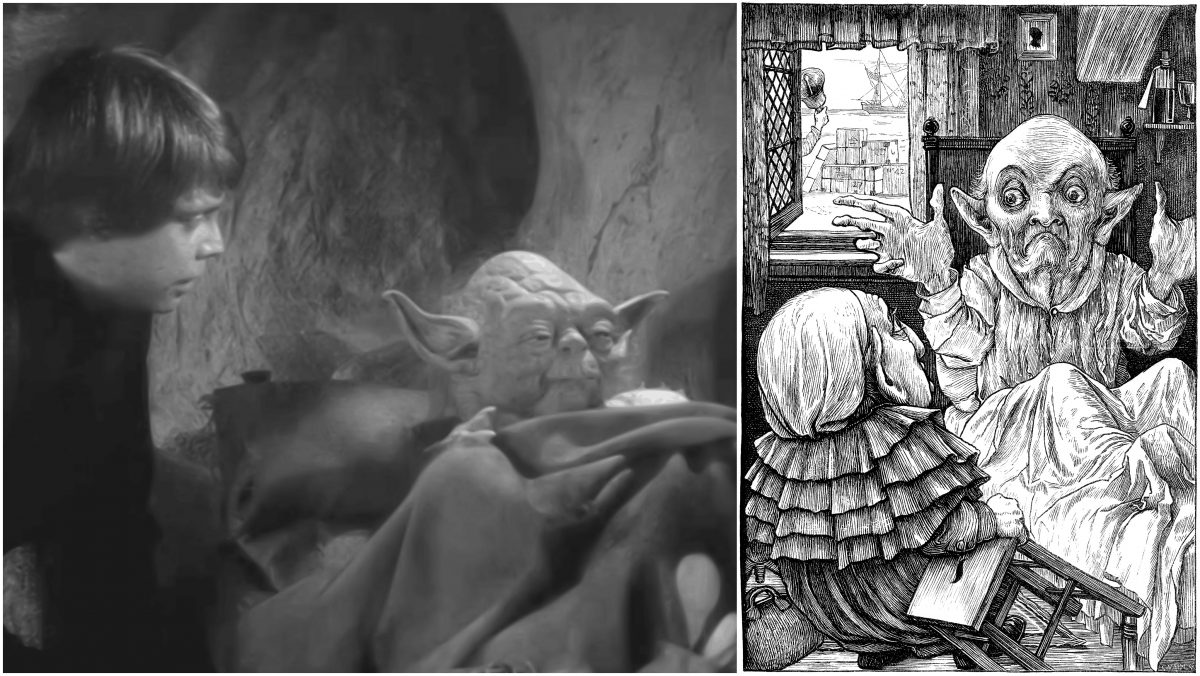

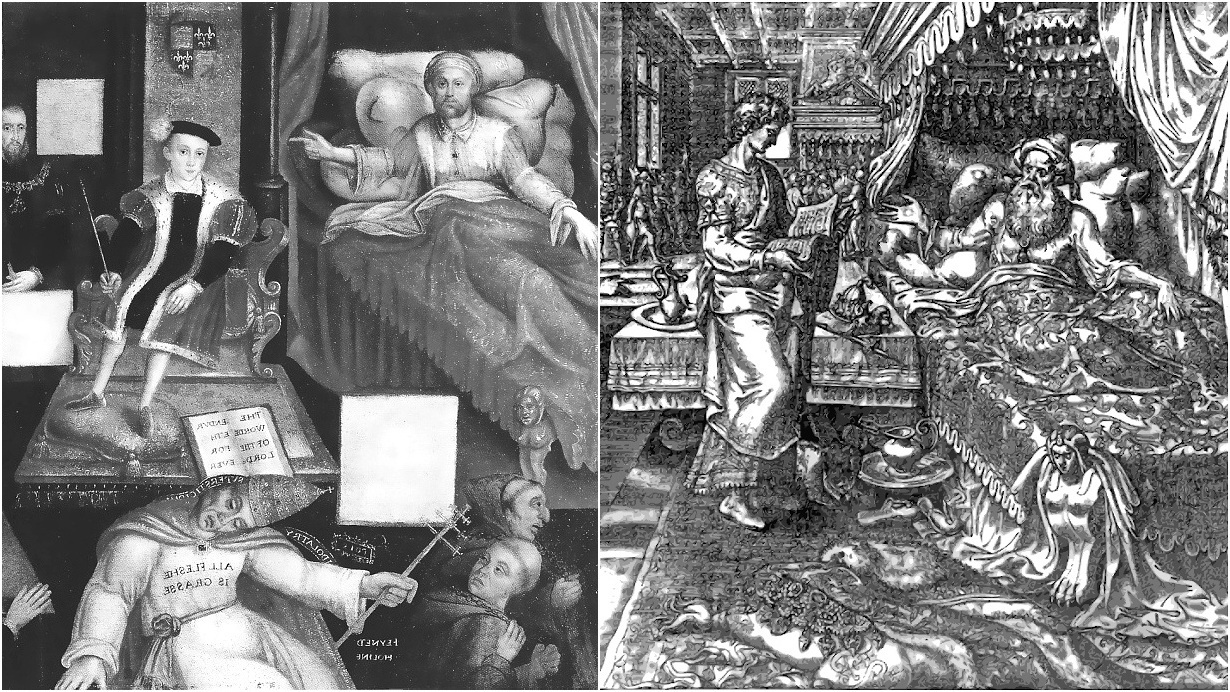

I think that Dodgson addressed conflicts within the Curch of England and the related legal battles (see

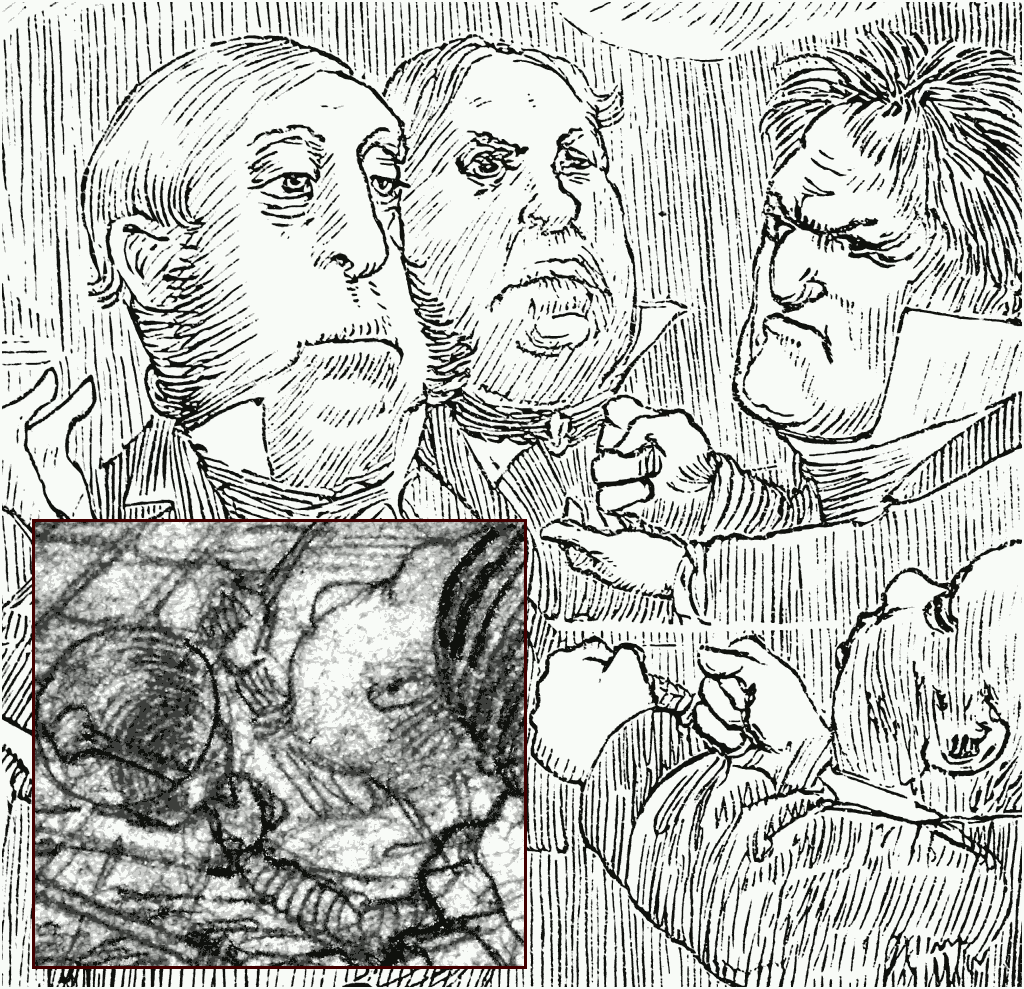

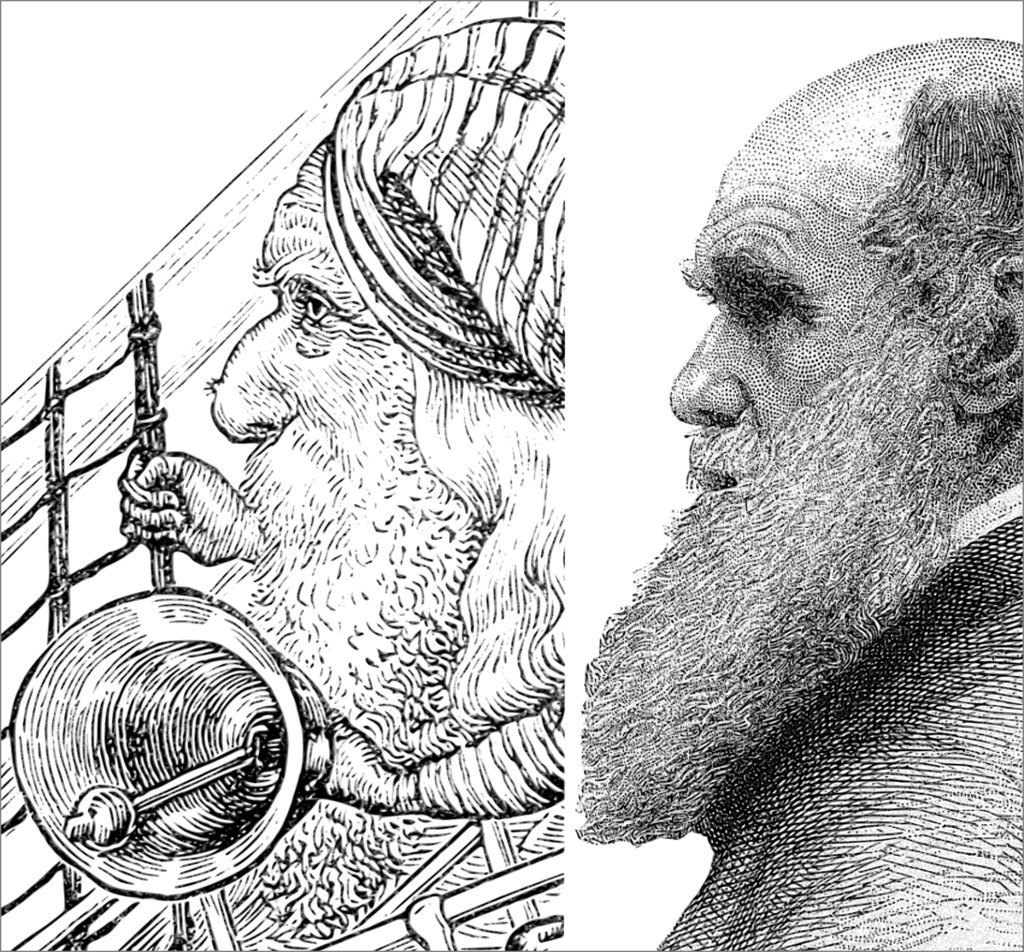

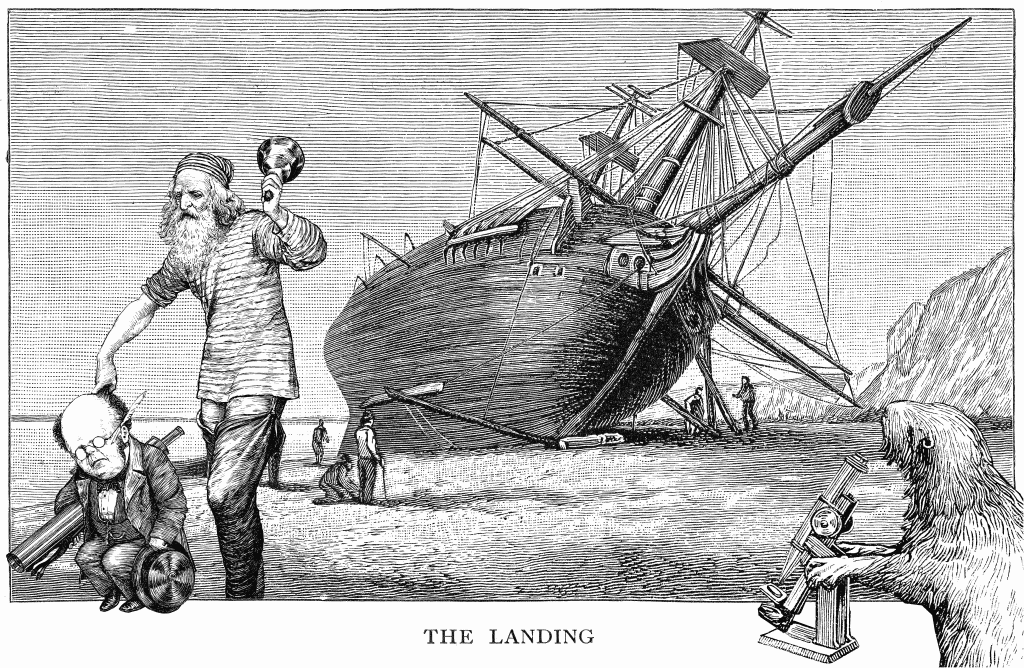

I think that Dodgson addressed conflicts within the Curch of England and the related legal battles (see  As for the looks, Richard Bethell, 1st Baron Westbury could be another candidate for Holiday’s reference.

As for the looks, Richard Bethell, 1st Baron Westbury could be another candidate for Holiday’s reference.

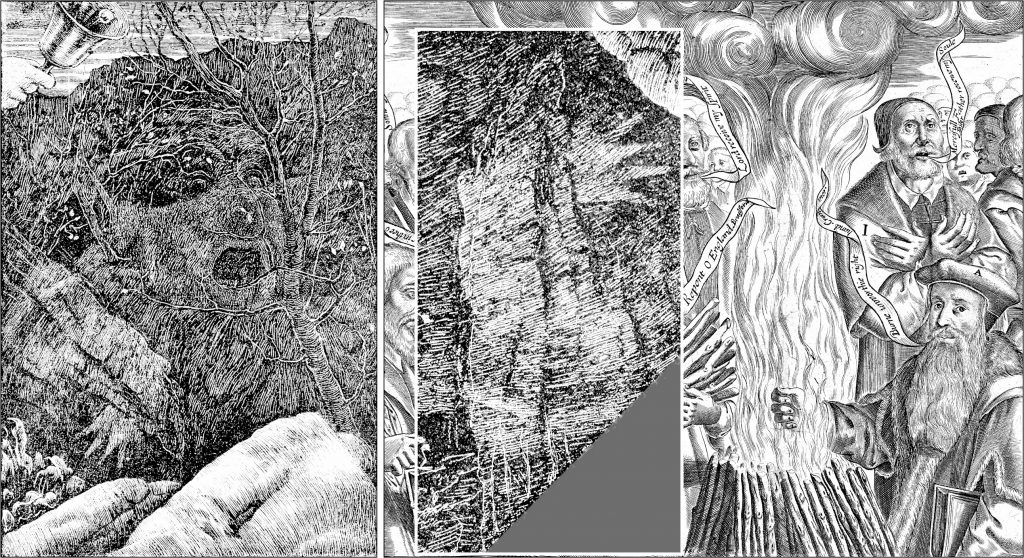

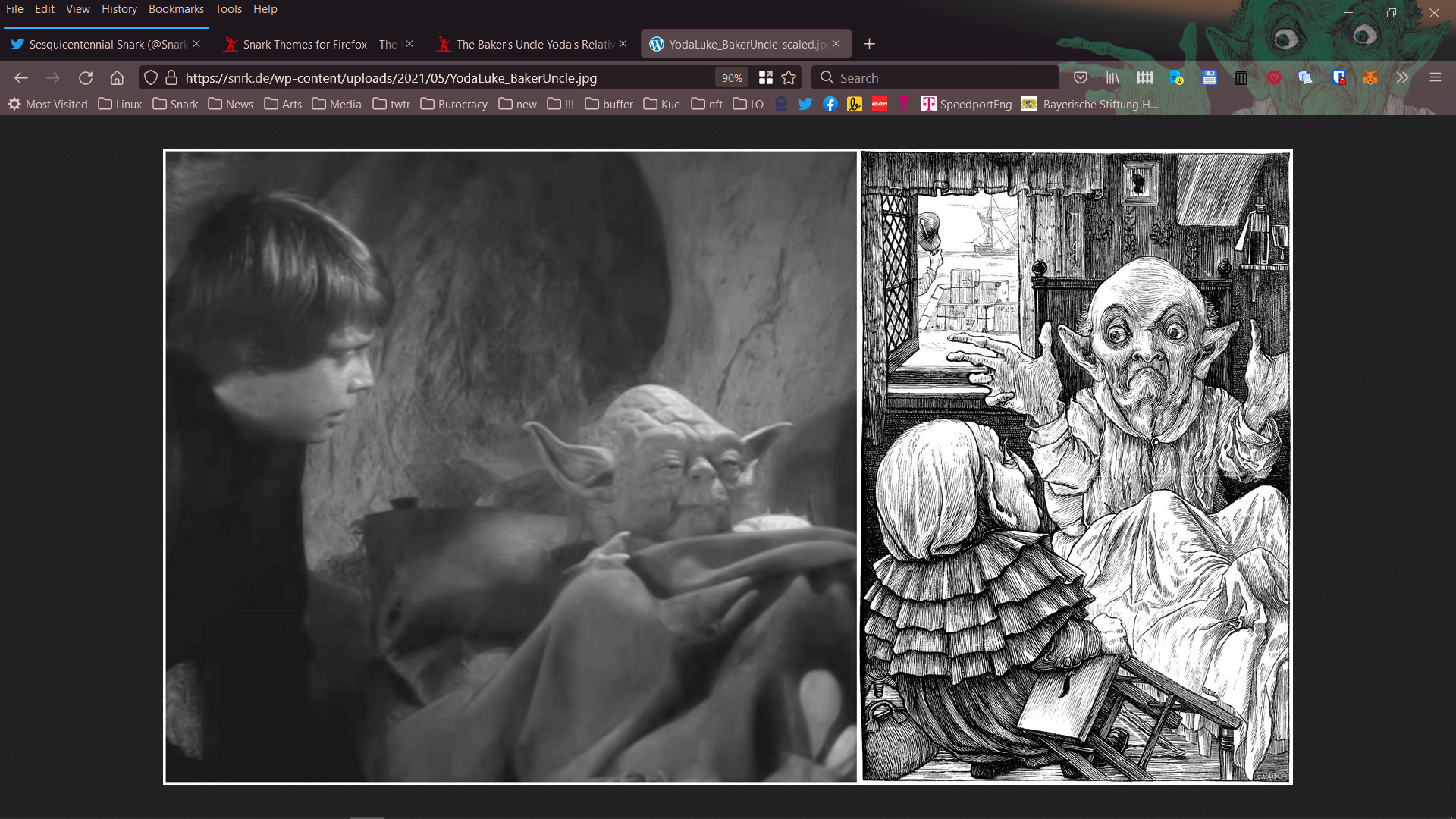

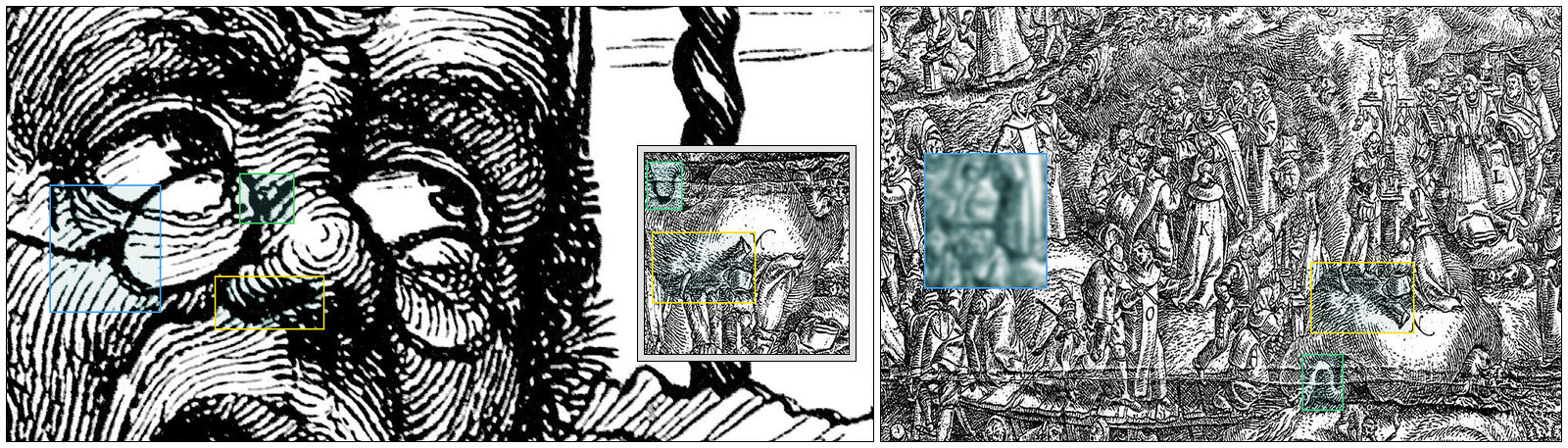

Left image

Left image

It consumes a power of 26 Watts. The F@H setting is “Full”. It’s a fan-less mini computer, so no tear&wear of an internal fan needs to be considered. But there is an external fan. The computer won’t get damaged by the heat, because it adapts the CPU clock frequency in a way which doesn’t let it get too hot. In winter it won’t reach maximum temperature anyway. But in summer its temperature limits will get tested, even though the ambient temperature will stay below the 50°C maximum. So I added an external fan (14W). My other computer is a laptop computer. I chose the “Light” setting (which means that the GPU will not be used for folding).

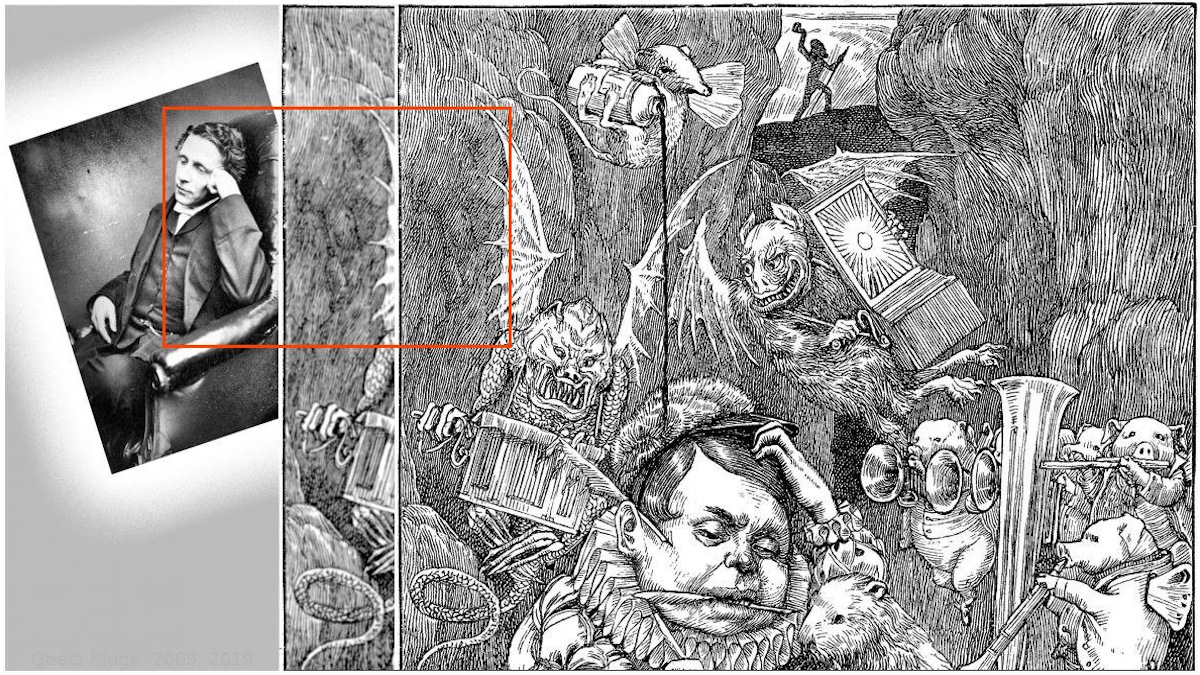

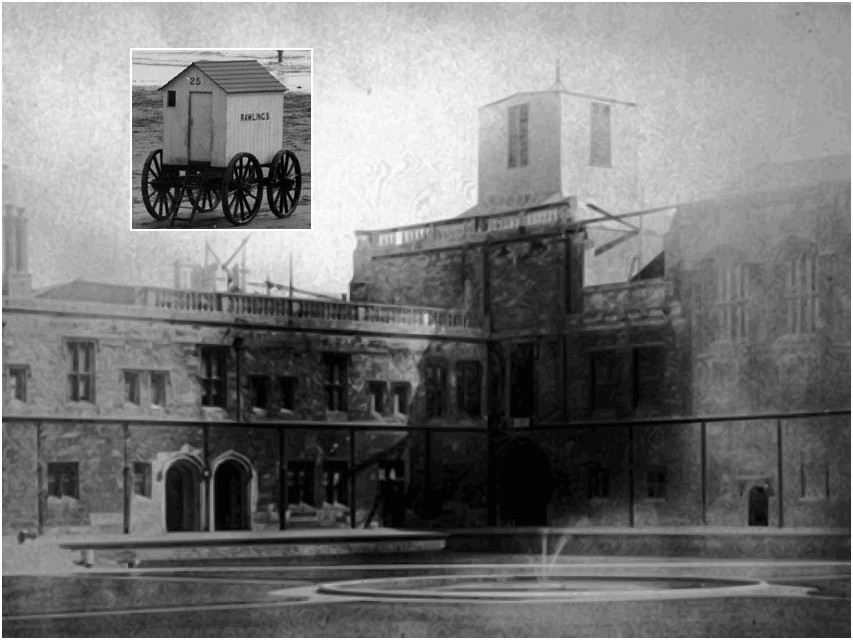

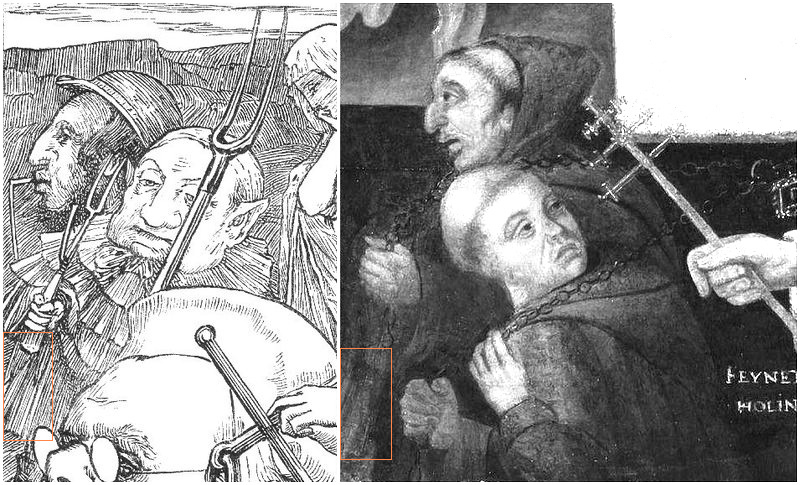

It consumes a power of 26 Watts. The F@H setting is “Full”. It’s a fan-less mini computer, so no tear&wear of an internal fan needs to be considered. But there is an external fan. The computer won’t get damaged by the heat, because it adapts the CPU clock frequency in a way which doesn’t let it get too hot. In winter it won’t reach maximum temperature anyway. But in summer its temperature limits will get tested, even though the ambient temperature will stay below the 50°C maximum. So I added an external fan (14W). My other computer is a laptop computer. I chose the “Light” setting (which means that the GPU will not be used for folding). LCSNA Fall Meeting, 2021

LCSNA Fall Meeting, 2021

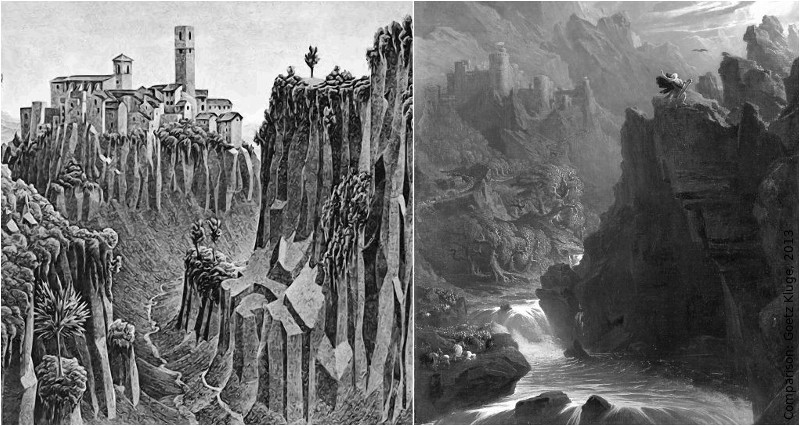

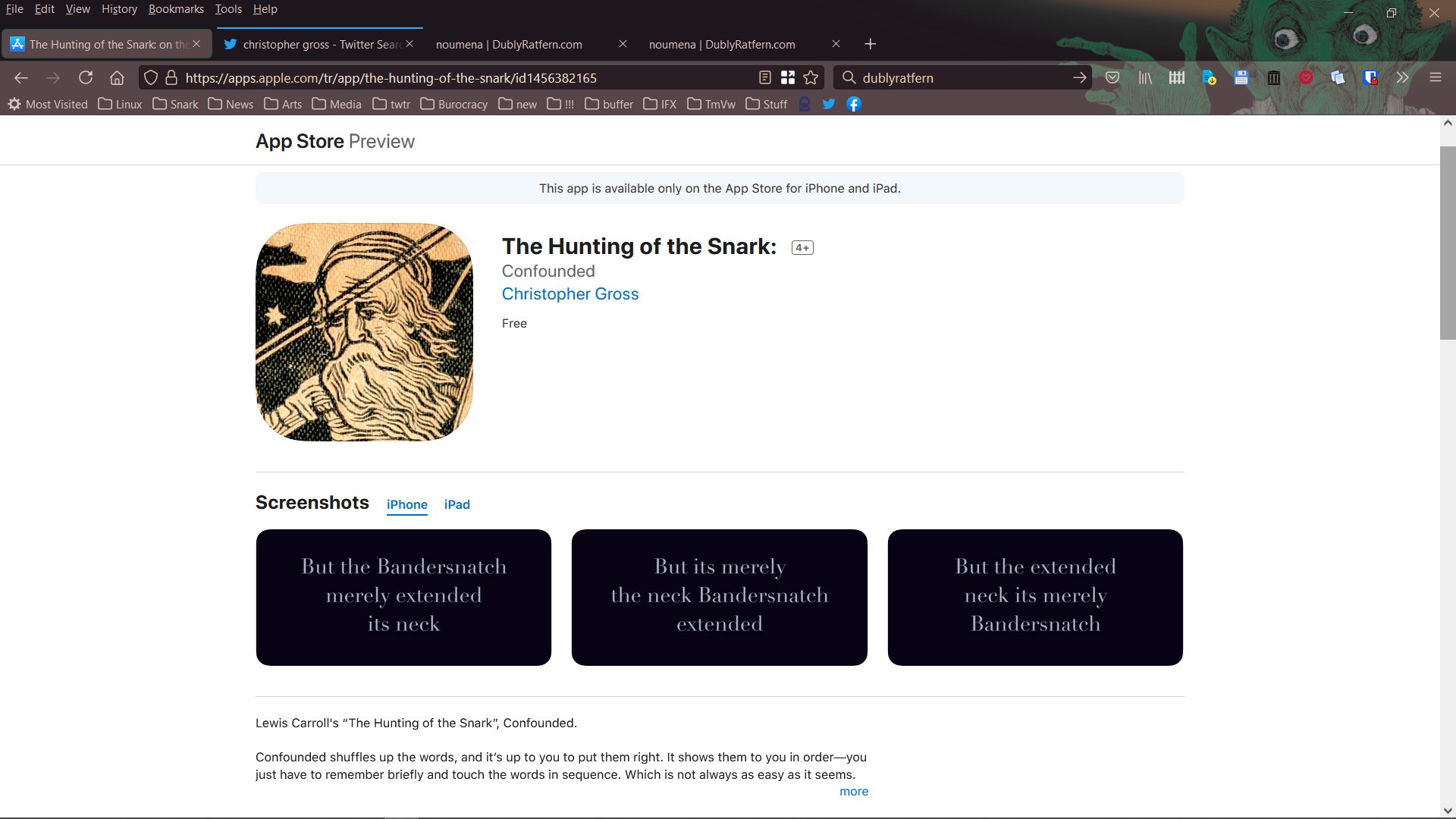

The Hunting of the Snark, Confounded

The Hunting of the Snark, Confounded