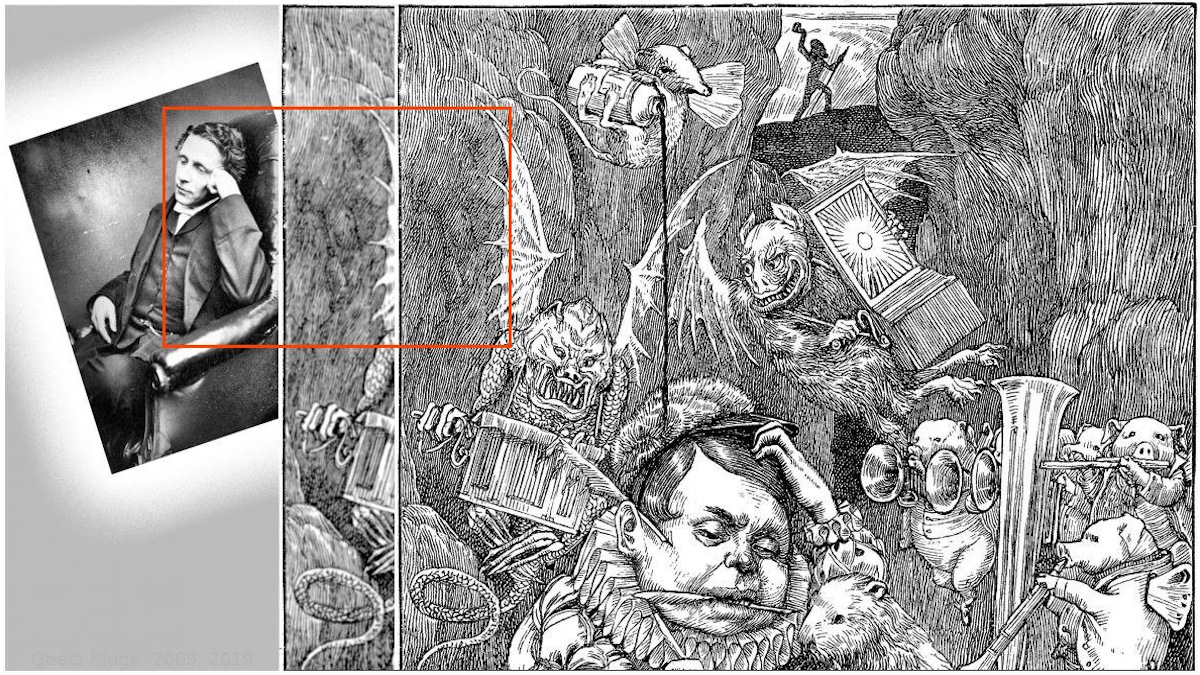

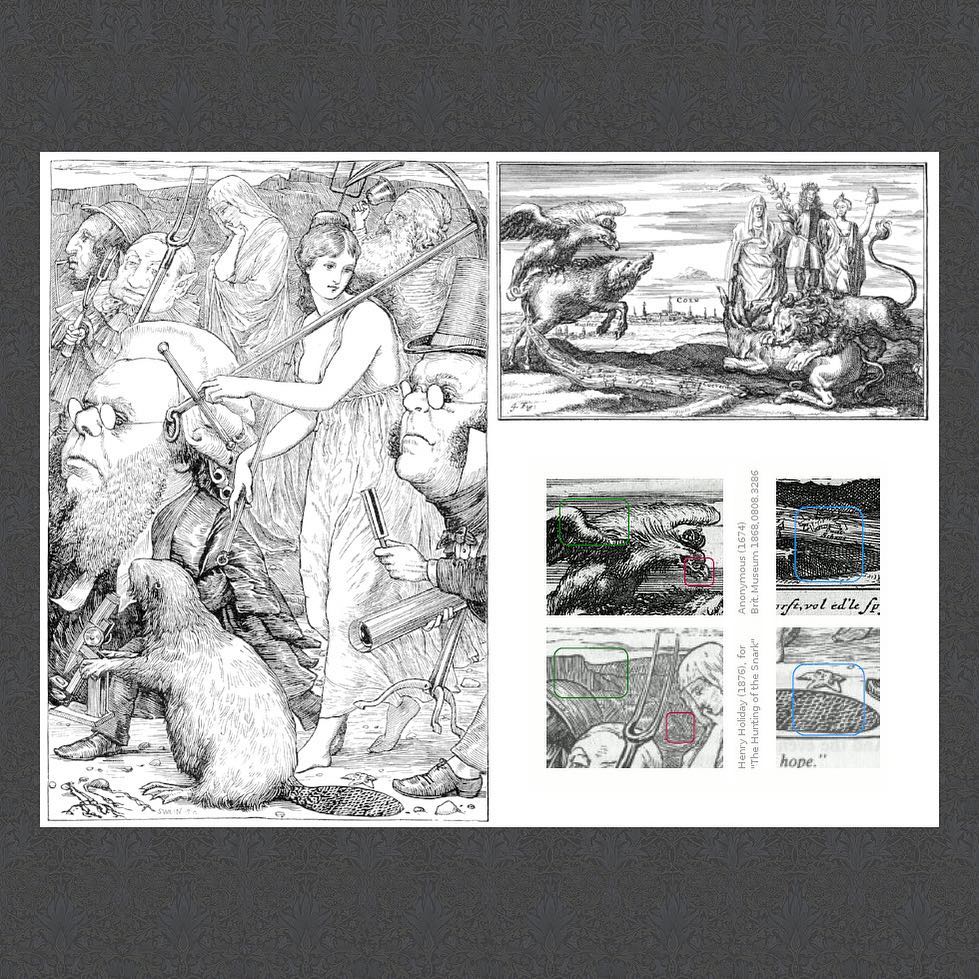

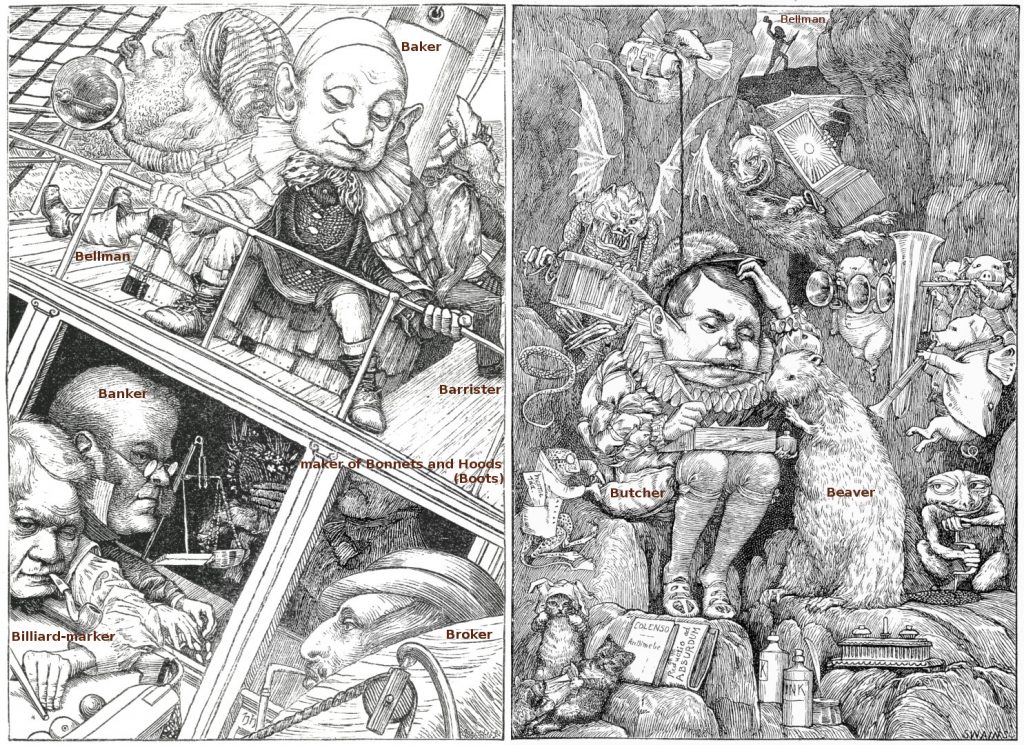

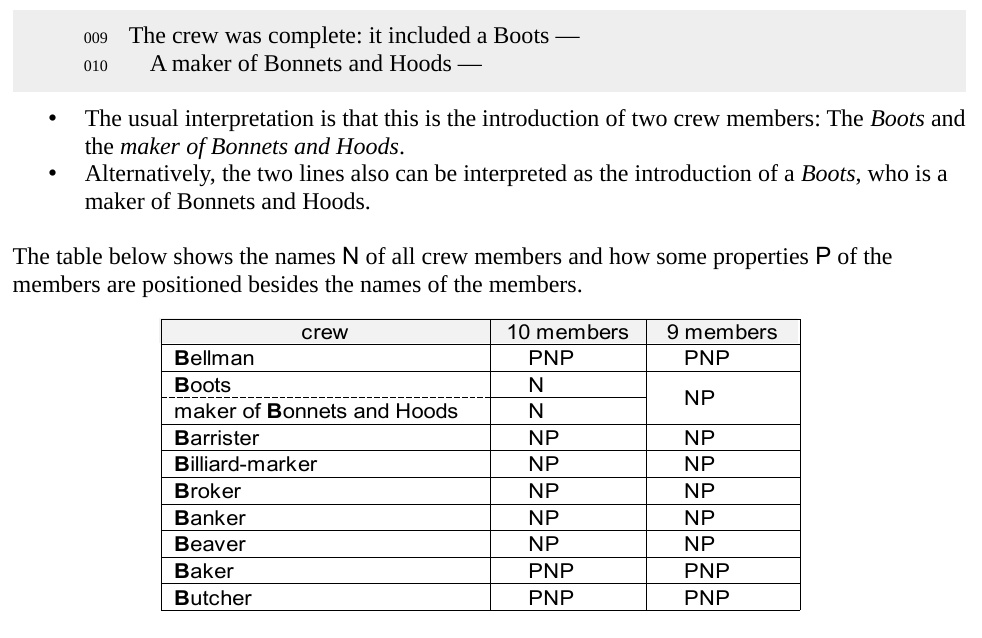

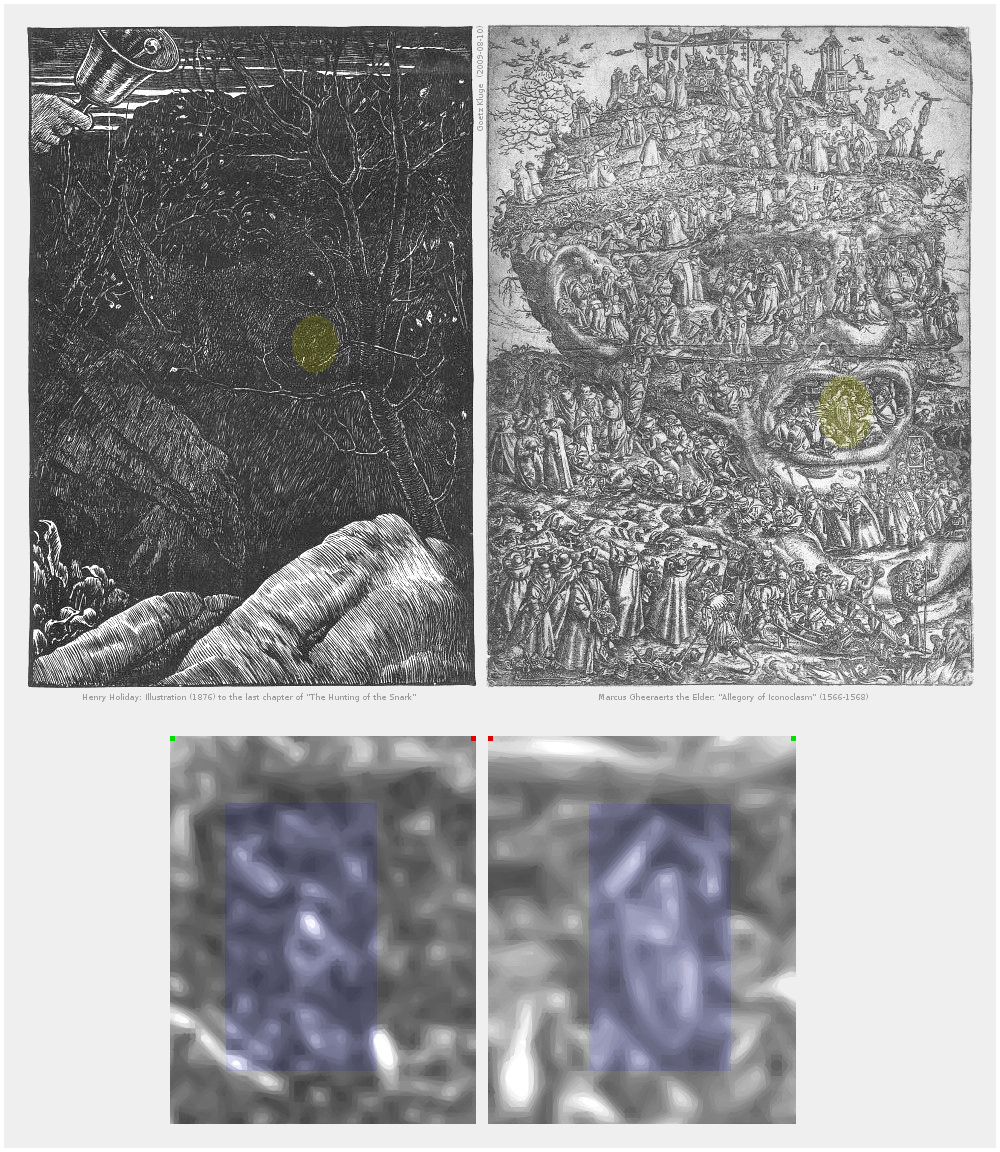

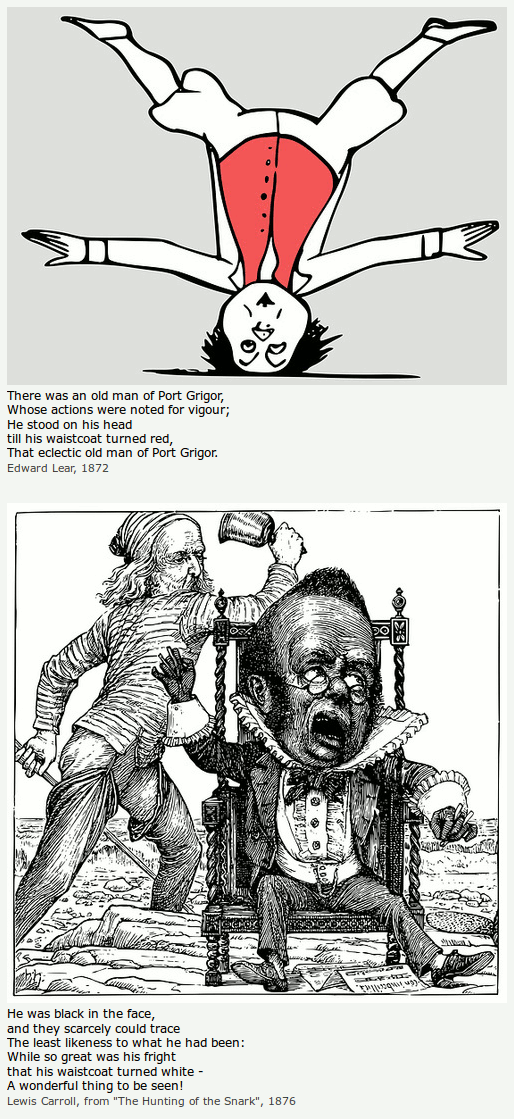

Most readers of The Hunting of the Snark assume that the Snark hunting party consists of ten members. However, probably for a good reason, only nine members can be seen in Henry Holiday’s illustrations to Lewis Carroll’s ballad. Actually, I really think that the Snark hunting party consists of nine members only. But if you, as almost everybody else, prefer ten Snark hunters, that’s fine too. Lewis Carroll gave you (and me) a choice, incidentally(?) in the 9th and the 10th line of his tragicomedy.

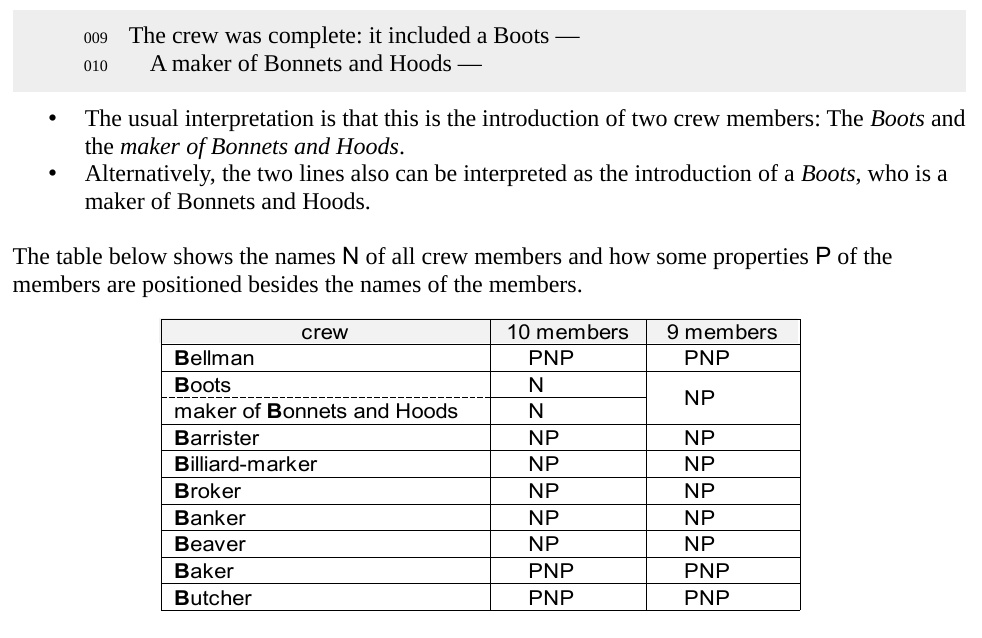

Let us take all the crew members in order of their introduction:

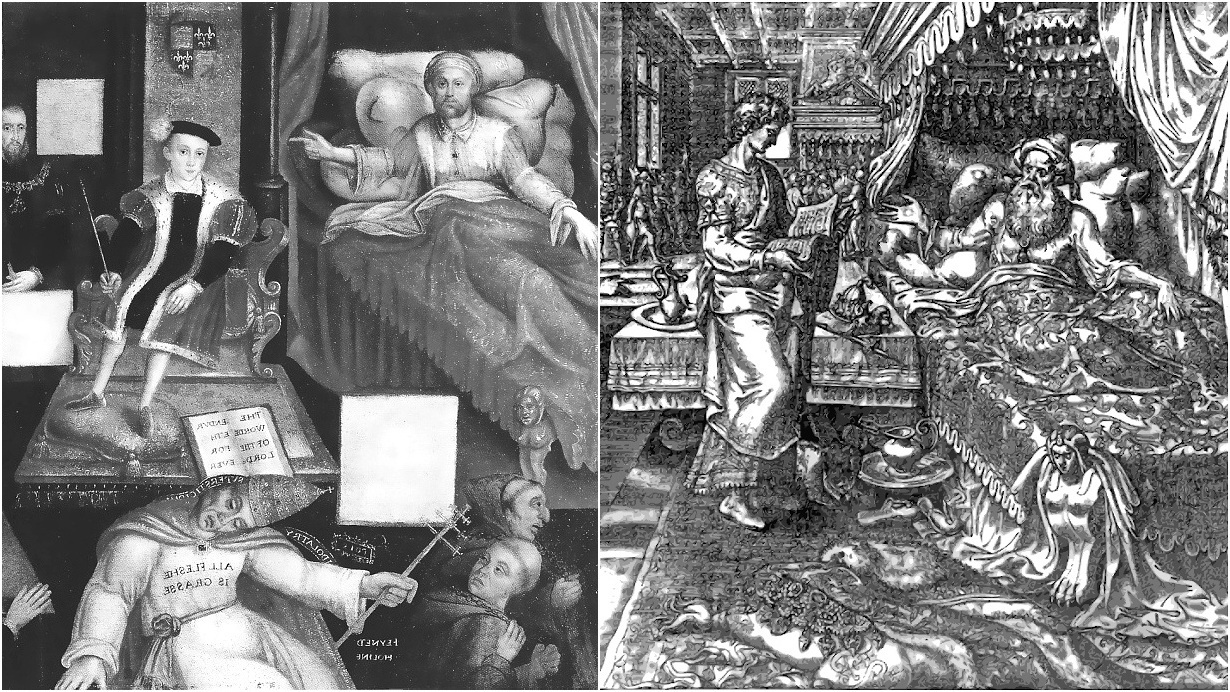

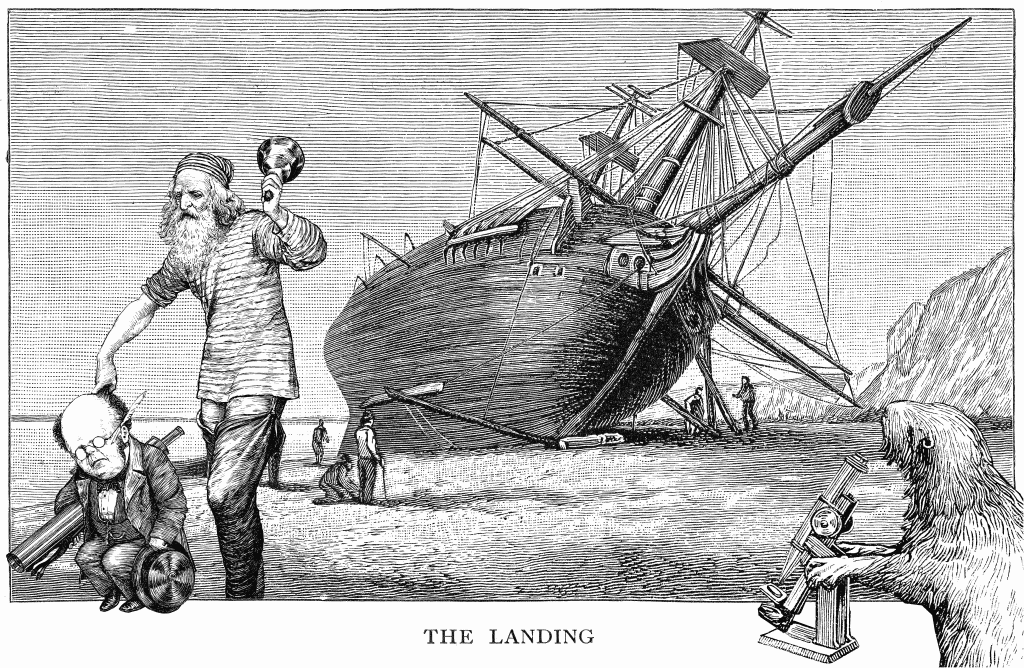

- The Bellman, their captain.

- The

Boots , a maker ofB onnets and Hoods .

(A non-sequential interlaced portmanteau can be built fromB onnets and Hoo ds.)

- The Barrister, brought to arrange their disputes, but repeatedly complained about the Beaver’s evil lace-making.

- The Broker, to value their goods.

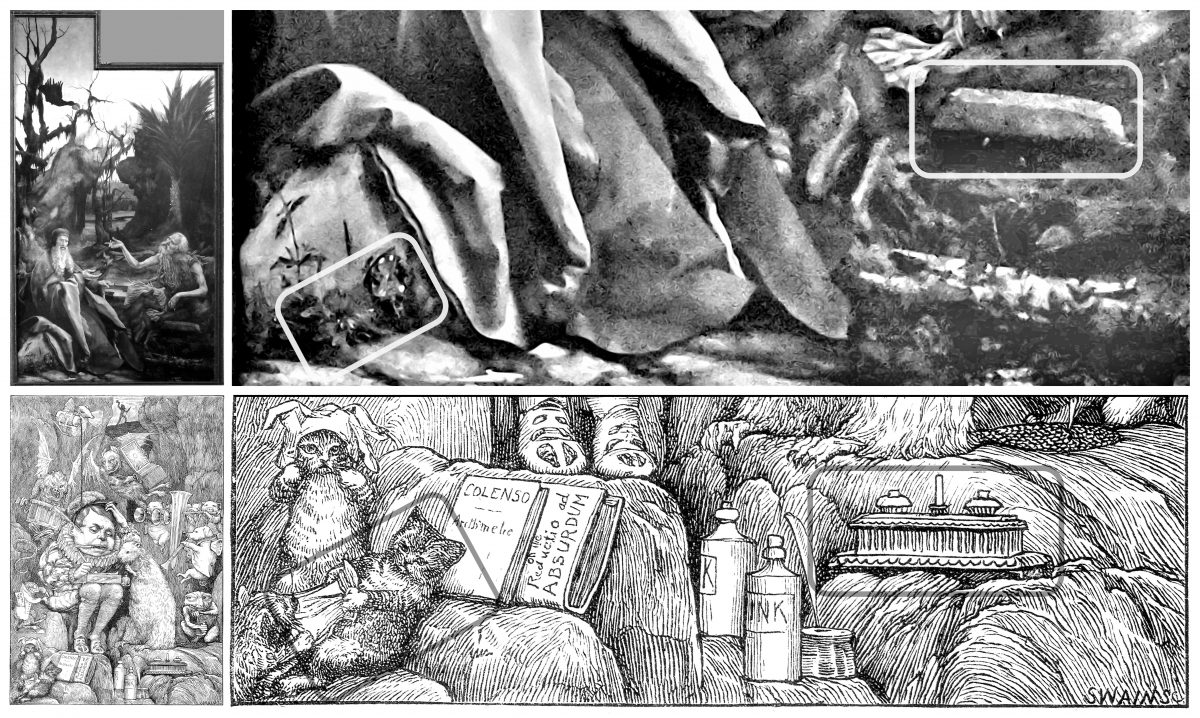

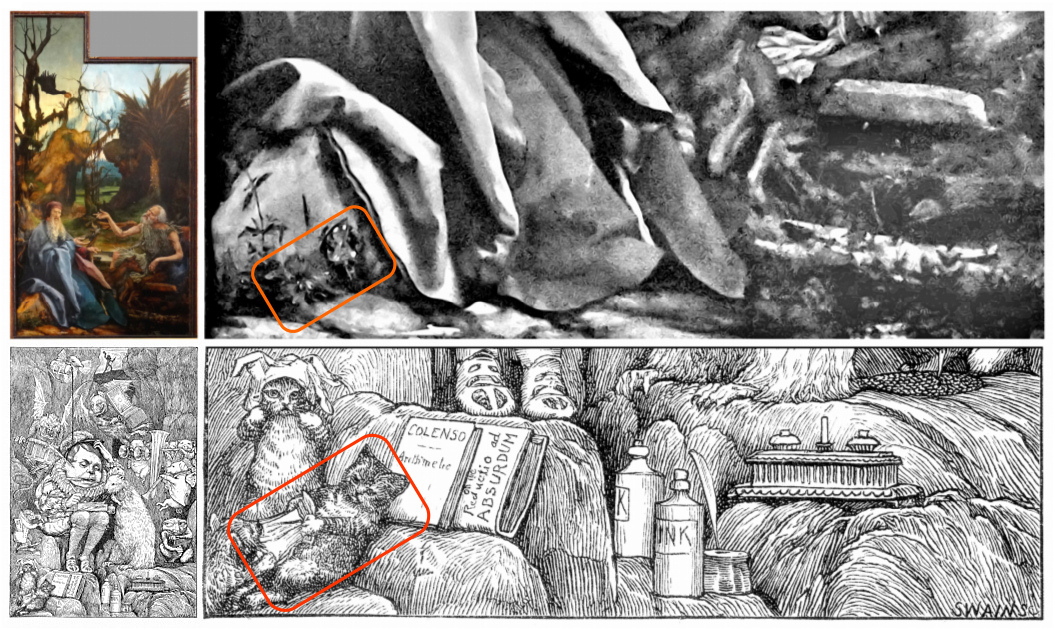

- The Billiard-marker, whose skill was immense, might perhaps have won more than his share. From John Tufail I learned that in Henry Holiday’s illustration the Billiard-marker is preparing a cheat.

- The Banker, engaged at enormous expense, had the whole of their cash in his care.

- The Beaver, that paced on the deck or would sit making lace in the bow and had often (the Bellman said) saved them from wreck, though none of the sailors knew how.

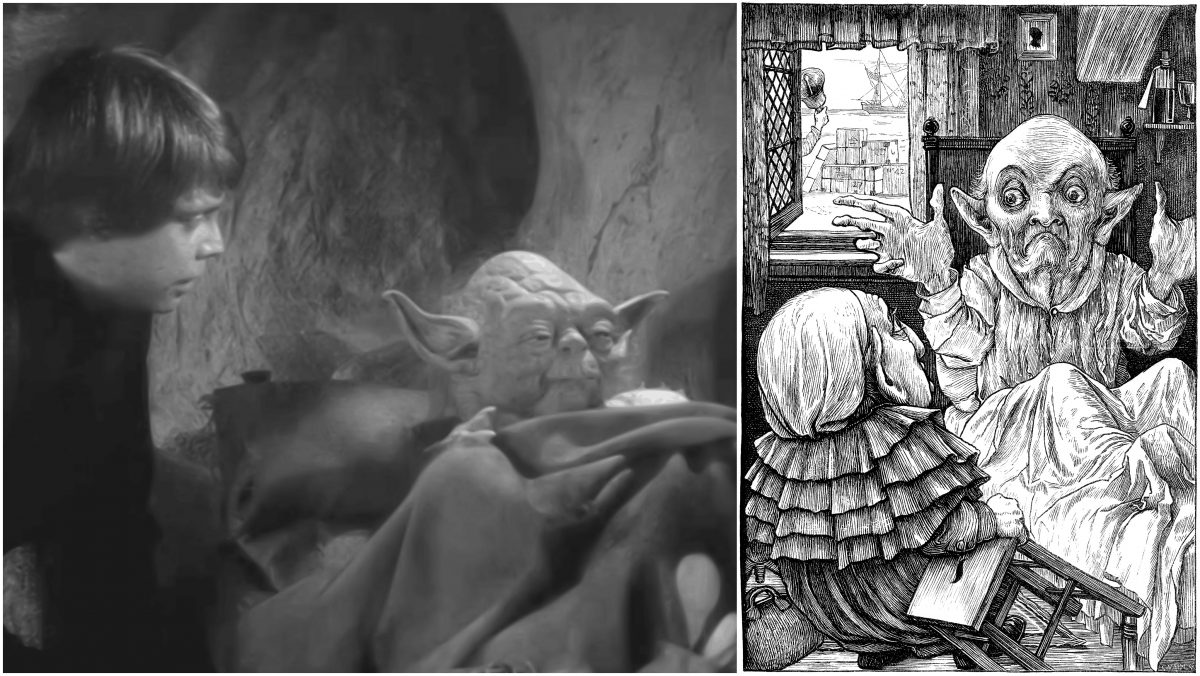

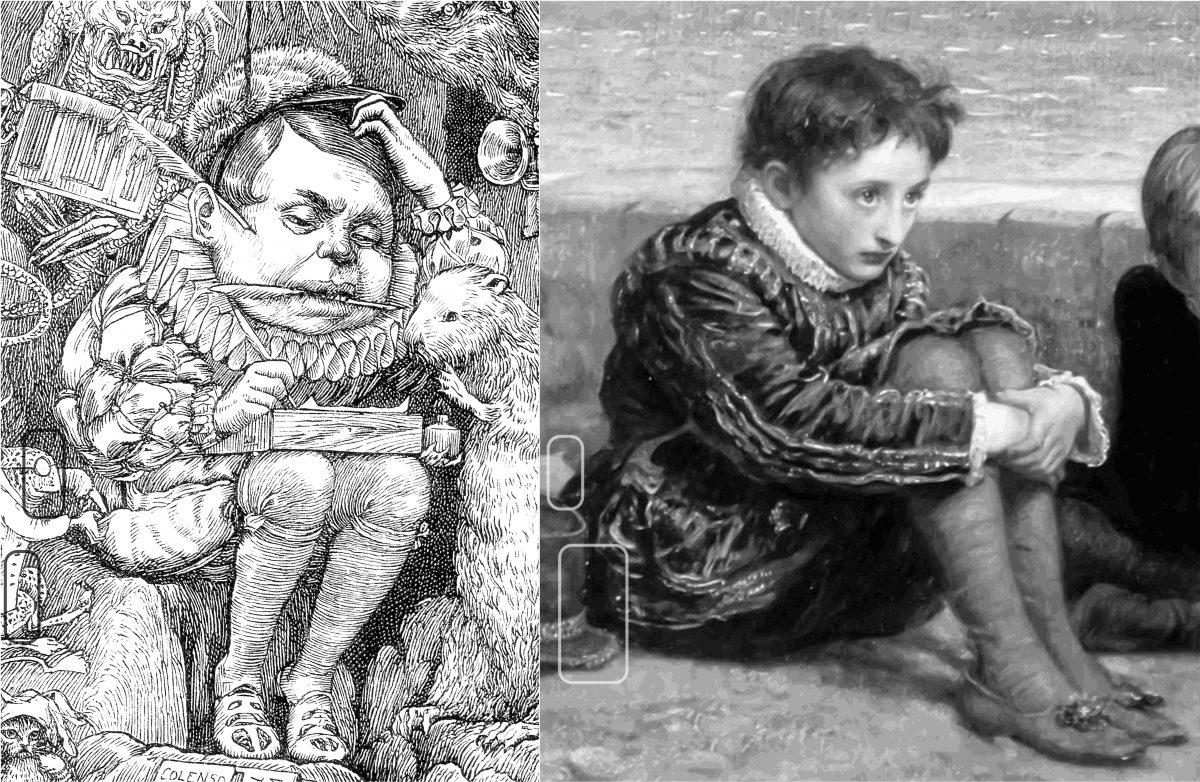

- The Baker, also addressed by “Fry me!”, “Fritter my wig!”, “Candle-ends” as well as “Toasted-cheese”, and known for joking with hyenas and walking paw-in-paw with a bear.

- The Butcher, who only could kill Beavers, but later became best friend with the lace-making animal.

More about the members of the Snark hunting party:

⭐ 9 or 10 hunters?

⭘ Care and Hope

⭘ The Snark

⭘ The Boojum

2017-11-06, updated: 2024-03-12

Martin Gardner annotated (

Martin Gardner annotated (