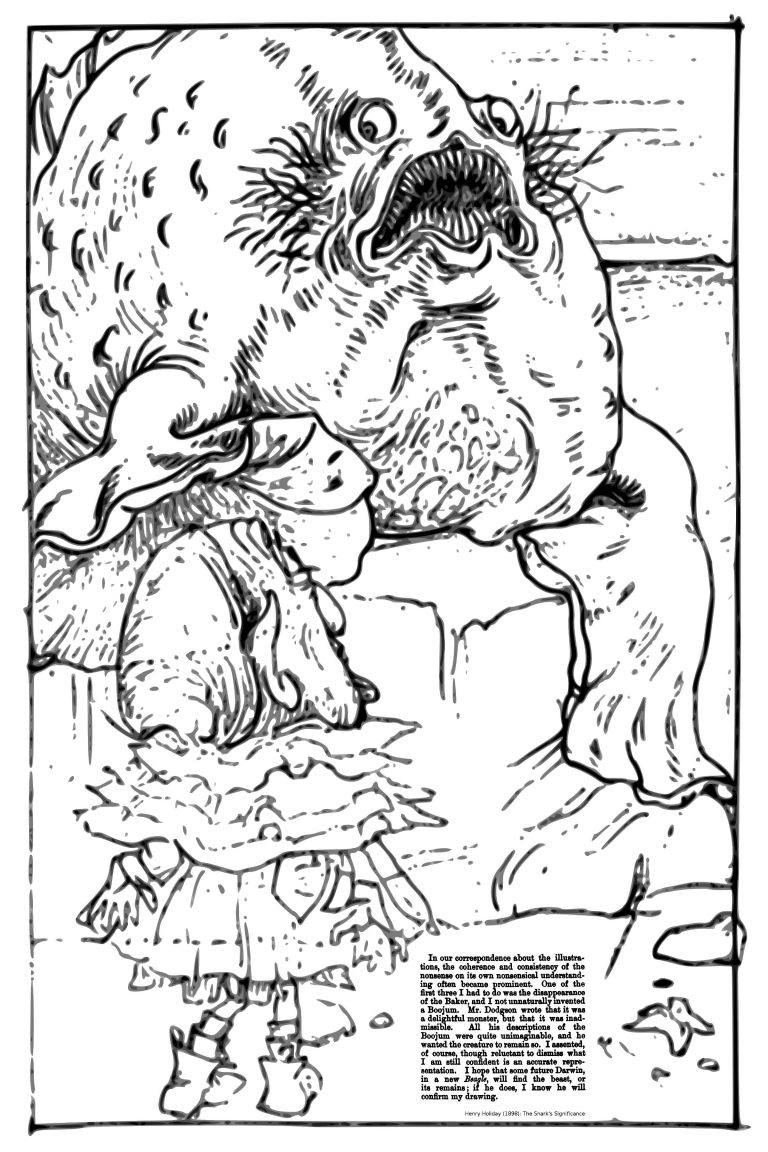

Lewis Carroll’s and Henry Holiday’s The Hunting of the Snark made me digging into British history and the history the Anglican church (especially the Oxford Movement).

It’s not history, at least not a finished one.

To me, Carroll’s tragicomedy (a tragedy in Henry Holiday’s view) is about the doctrinal conflicts (some of them lethal) arising along the travel to truth, whatever that might be. These conflicts within and between belief systems surely didn’t end today. Also the concrete disputes which might have inspired the Rev. Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) in the 19th century seem to be going on even today. All that is quite strange to me (not only because I am a German). I can’t take sides, because I don’t even understand how and why the disputed issues can be issues at all.

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/church-england-has-sent-clear-message-its-conservative-churchgoers-youre-not-wanted-1611289:

The Church of England has sent a clear message to its conservative churchgoers – you’re not wanted.

The treatment of Bishop Philip North, an Anglo-Catholic, shows the Church’s prospects for unity are grim.

By Andrew Sabisky March 13, 2017 13:16 GMT

It is with a heavy heart that I must announce that the Church of England is at it again. Fresh off a truly disastrous session of General Synod (the Church’s parliament), it has plunged itself headlong into further public ignominy.

The latest disaster concerns Bishop Philip North, currently the Bishop of Burnley. He was chosen by the bureaucracy to be the new Bishop of Sheffield (a promotion from suffragan to diocesan status). […]

Not only the ongoing struggles in the Anglican Church still are turning Snarks into Boojums. The multicultural beasts are very alife today, perhaps more than ever.

106 … the Captain they trusted so well

107 Had only one notion for crossing the ocean,

108 And that was to tingle his bell.

109 He was thoughtful and grave—but the orders he gave

110 Were enough to bewilder a crew.

111 When he cried “Steer to starboard, but keep her head larboard!”

112 What on earth was the helmsman to do?

113 Then the bowsprit got mixed with the rudder sometimes:

114 A thing, as the Bellman remarked,

115 That frequently happens in tropical climes,

116 When a vessel is, so to speak, “snarked.”

117 But the principal failing occurred in the sailing,

118 And the Bellman, perplexed and distressed,

119 Said he had hoped, at least, when the wind blew due East,

120 That the ship would not travel due West!

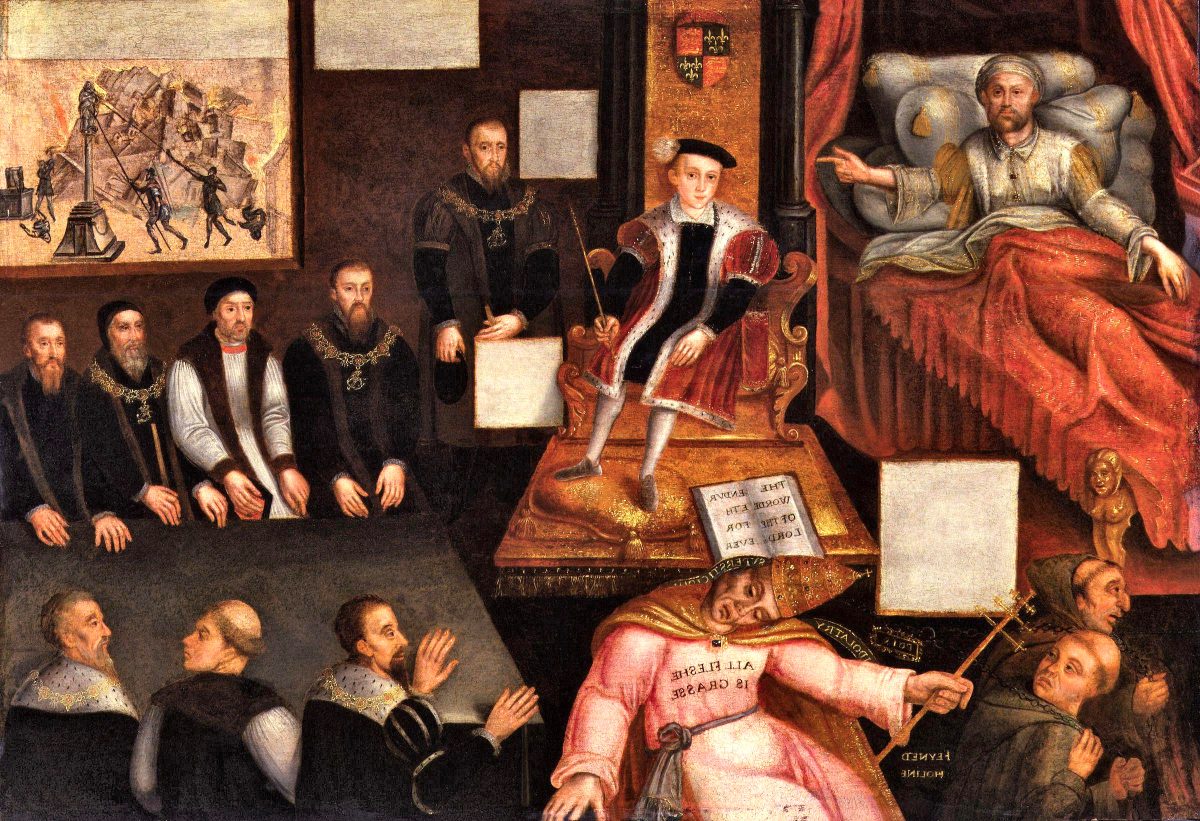

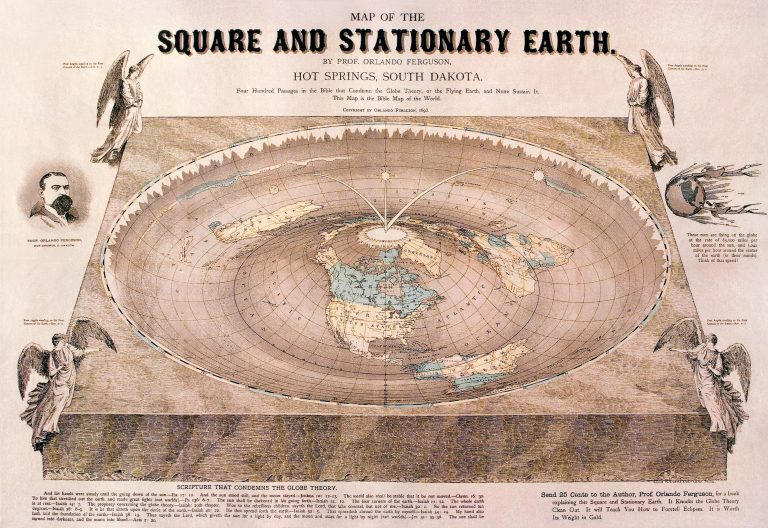

Beyond Oxford and beyond the church, Carroll’s tragicomedy also applies to the conflicts (some of them lethal) arising along the travel to truth in worldly matters. In the last years more and more Boojums got in the way of the travellers. Most of them are notorious liars. How evil they are you’ll understand if you see what kind of leadership they admire.

1st post: 2017-01-21, update: 2018-08-07

Image source:

Image source: