Image from: wikimedia.org:

Millais’ Lorenzo and Isabella caused some noise in November 2012 on occasion of Tate’s Pre-Raphaelites exhibition. Only then the phallic symbol was mentioned openly by a museum, even though “The gallery staff at the Walker Art Gallery have been mischievously pointing it out to (adult) visitors for years : )”. More than 160 years after Millais drew the painting, Millais’ “shadow” finally was allowed to help advertising the Pre-Raphaelites exhibition.

This is bycatch from my Snark hunt, not one of my Snark comparisons. It is about “seeing” things in paintings and illustrations. When I started my Snark hunt, I often wondered why people are afraid to tell what they see. Afraid of embarrasment?

This is bycatch from my Snark hunt, not one of my Snark comparisons. It is about “seeing” things in paintings and illustrations. When I started my Snark hunt, I often wondered why people are afraid to tell what they see. Afraid of embarrasment?

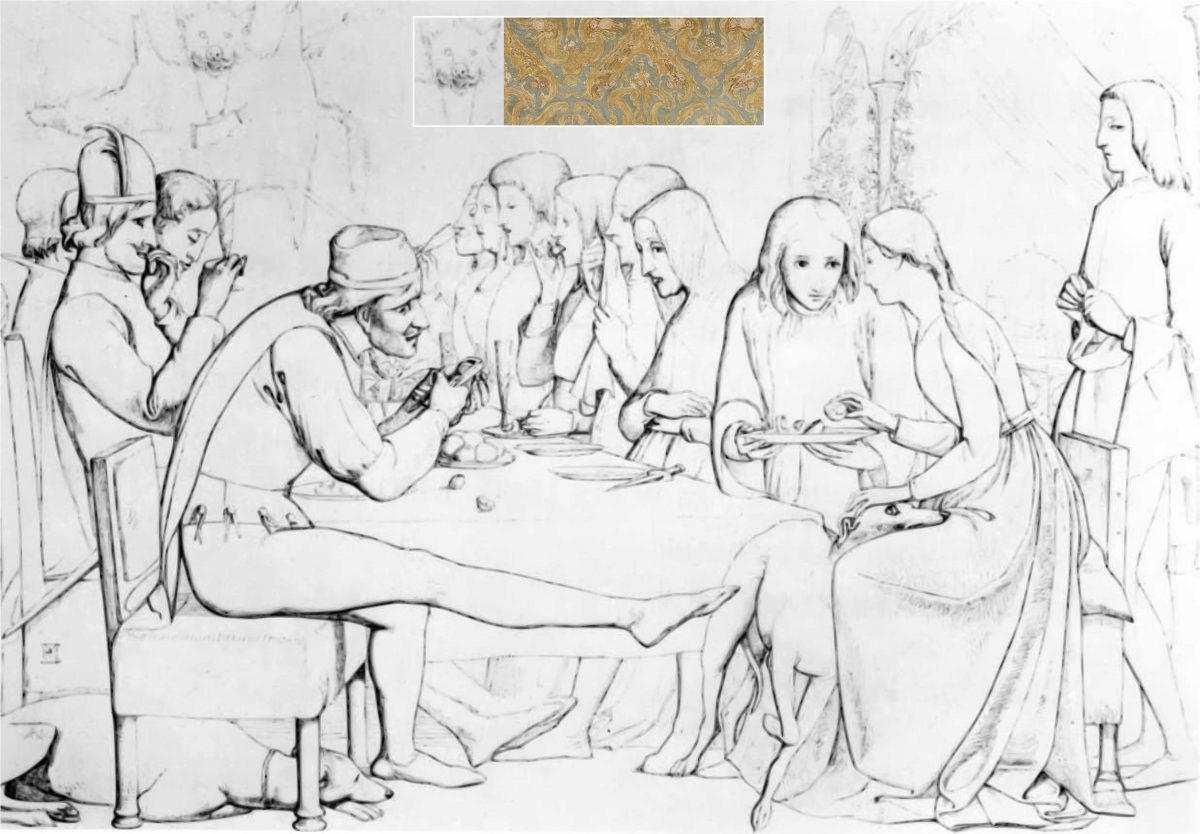

John Everett Millais’ painting Lorenzo and Isabella (created: 1848–1849; present location: National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery; inspired by John Keats’ poem Isabella) could help us to explain the shyness of beholders if it comes to seeing ambiguous objects in images.

In November 2012 the Liverpool museums page said (but doesn’t say it anymore):

[…] On the table there is spilled salt, symbolic of the blood which will later be spilled. The shadow of the arm of the foremost brother is cast across this salt, thus linking him directly with the future bloodshed. […]

In June 2013 I noticed that the “shadow of the arm” and all that has disappeared from the 2012 Liverpool Museum’s page. Another page said:

[…] Elsewhere in the picture, murder is prefigured: another brother hold up a glass of blood-like wine; a hawk pecks at a white feather; salt, symbol of life, is spilt on the table; scenes of violence decorate the majolica plates; the pot of basil stands ready on the balcony to receive the murdered man’s head. […]

As of 2018-10-15, the Liverpool Museum’s page (http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/collections/preraphaelites/item-237002.aspx) says

[…] One of the brothers is shown aiming a kick at Isabella’s dog, while the lovers share a blood orange, signifying the later spilling of Lorenzo’s blood. […]

Here it is the blood orange signifying the later spilling of Lorenzo’s blood. No mentioning of the phallic shadow, even though the meaning of that shadow is not really a secret anymore. The reproduction of Millais’ painting on top of this page shows a detail from the depiction of one of Lorenzo’s brothers where you see that the young Millais left quite visible traces when he re-positioned the elbow of that thug. Perhaps he needed more space for the shadow and the salt. Instead of the shadow of the arm of the foremost brother being cast across the salt, the the salt is cast across the shadow! And what a strange shadow that is. The shadow covers the white table cloth, but miraculously does not cover the white salt.

2021-02-06: https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/isabella:

[…] One of the brothers is shown aiming a kick at Isabella’s dog, while the lovers share a blood orange, signifying the later spilling of Lorenzo’s blood. […]

They keep beating around the bush.

Let’s have a look at the Wikipedia: On 2016-11-04 the WP article on Millais’ painting was extended:

Hidden phallic symbols: In 2012, British art curator Carol Jacobi discovered several likely intentional sexual symbolisms in the painting. They were all on or near the character in the front left, who is stretching out his leg and using a nutcracker. The shadow on the table near his crotch area, his leg, and the nutcracker were all argued to represent a phallus. Jacobi said: “The shadow is clearly phallic, and it also references the sex act, with the salt tipped into the shadow.” She also argued that it would have been delibirate, but did not know what the painter’s intention with it was. However, she stated that it was “not a Freudian slip, or a hypocritical, furtive innuendo. The imagery of masturbation and the anxieties around it and being unable to control yourself sexually would have been well known.” [2][3]

Carol Jacobi wrote (and the WP article referred to it) against such “unseeing” (Sugar, Salt and Curdled Milk: Millais and the Synthetic Subject, Tate Papers, no.18, Autumn 2012, accessed: 2018-01-02):

[…] This essay looks at a pattern of sexual images ‘lost in the effort of reading’. Some, such as the phallic shadow projecting from the groin of the foreground figure in Lorenzo and Isabella 1848–9 […], appear to have been unseen, having attracted no mention in critical commentaries of the work. […] The salt cellar spilling its contents through the shadow on the white cloth in Lorenzo and Isabella, dispels doubts about whether such sexual connotations were ‘conscious’. […]

Well, it’s over the shadow, not through the shadow. We might guess what meaning the salt might have. But it is clear beyond guessing that Millais painted something which is impossible: White Salt covers the shadow. However, in the real world it would be the shadow which covers the salt. The imagery of masturbation and the anxieties around it and being unable to control yourself sexually would have been well known to Millais, but to this painter the the laws of optics were well known too. Thus, the intention of Millais simply could have been to draw the salt and the shadow in a way which makes very clear that the salt covered shadow is no shadow.

In a 1848 draft there still was no such shadow: The hunting trophies at the wall (upper left side) didn’t make it into the painting. You can see a pig head, the fur of some animal and a blowing horn. The pig head perhaps inspired the pattern which the young Millais used for the wallpaper.

The hunting trophies at the wall (upper left side) didn’t make it into the painting. You can see a pig head, the fur of some animal and a blowing horn. The pig head perhaps inspired the pattern which the young Millais used for the wallpaper.

2017-12-31, update: 2022-07-12