modified from eBooks@Adelaide

2007

2009-01-20, Götz Kluge added: Easter Greeting, Carroll's dedication to Gertrude Chataway,

line numbering and better images.

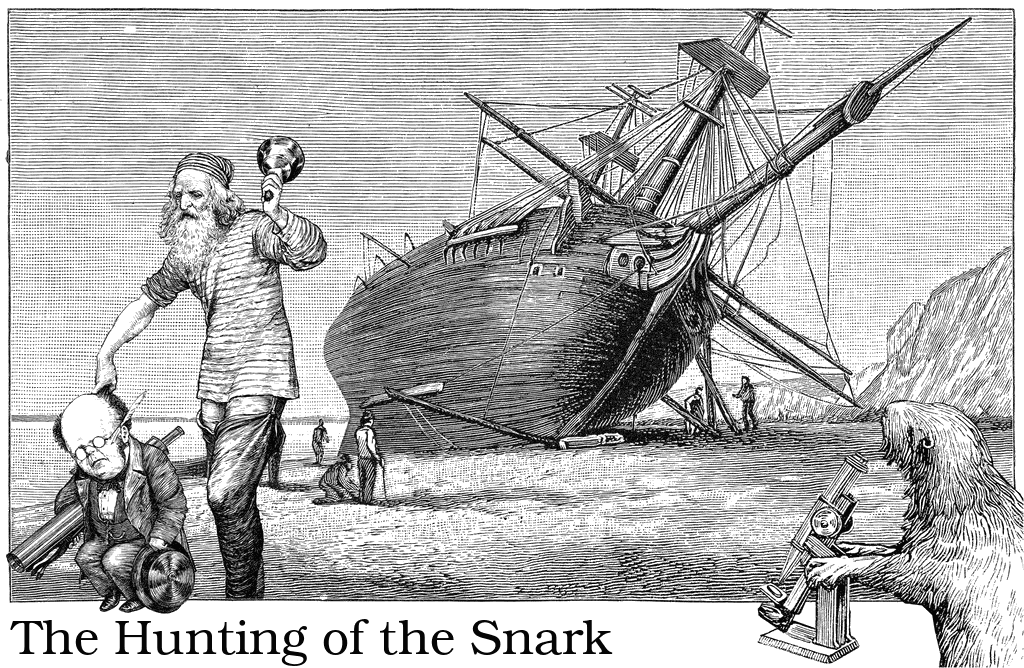

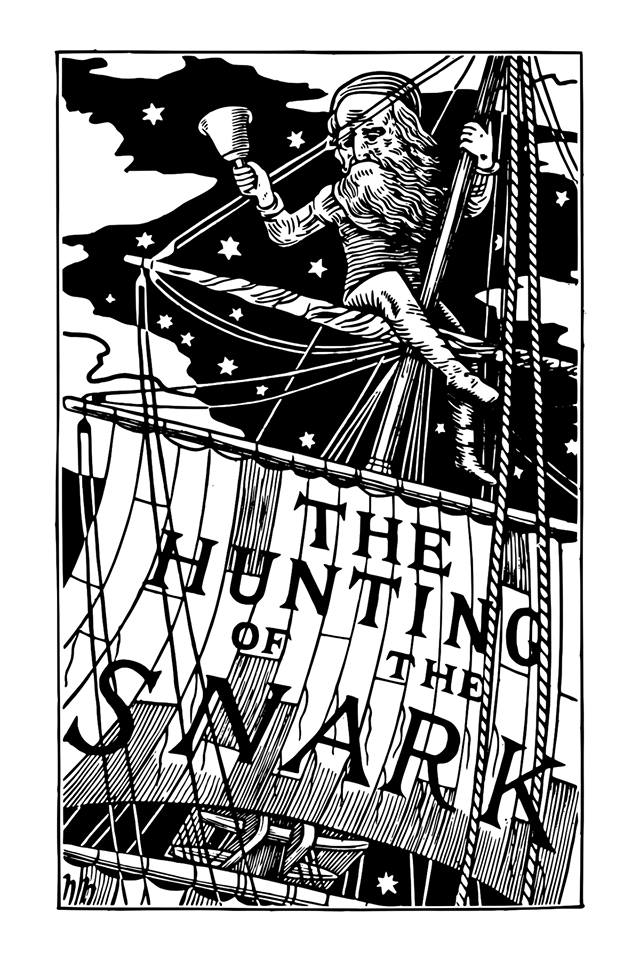

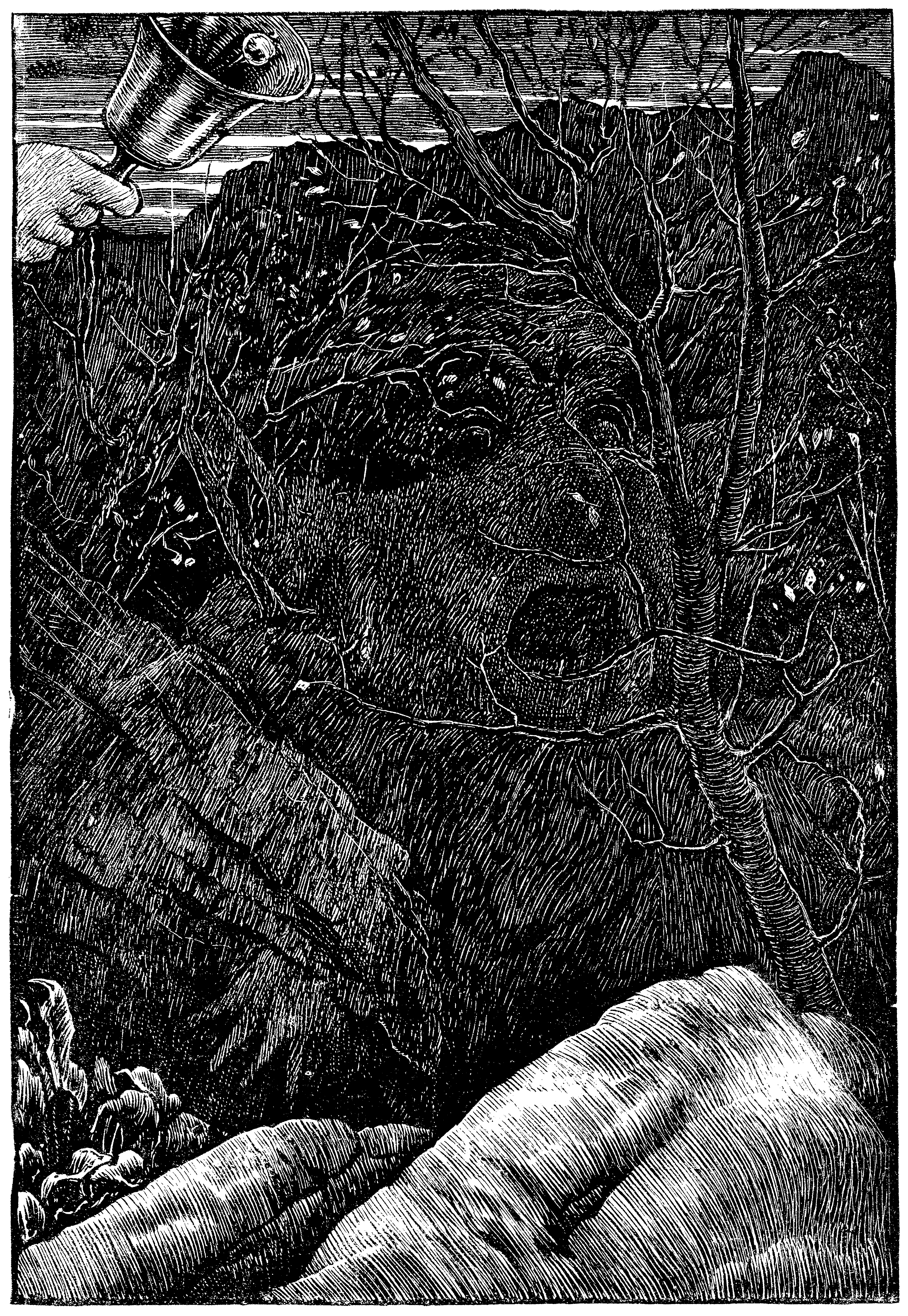

(The cover image is an assemblage by Götz Kluge

based on artwork by C. Martens & T. Landseer, H. Holiday & J. Swain.)

Last update: 2024-06-19.

This is a mirrored and modified web edition

of a file which originally has been published by eBooks@Adelaide.

Rendered into HTML by Steve

Thomas.

Last updated Sat Jan 13 17:38:15 2007.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence

(available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/au/).

You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work,

and to make derivative works under the following conditions: you

must attribute the work in the manner specified by the licensor;

you may not use this work for commercial purposes; if you alter,

transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the

resulting work only under a license identical to this one. For any

reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license

terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you

get permission from the licensor. Your fair use and other rights

are in no way affected by the above.

This modified work is available at

//snrk.de/snarkhunt/

(Modifications:

Carroll's dedication to Gertrude Chataway,

Easter Greeting

Source of original file:

eBooks@Adelaide

The University of Adelaide Library

University of Adelaide

South Australia 5005

TO

EVERY CHILD WHO LOVES

"Alice"

DEAR CHILD,

Please to fancy, if you can, that you are reading a real letter, from a real friend whom you have seen, and whose voice you can seem to yourself to hear wishing you, as I do now with all my heart, a happy Easter.

Do you know that delicious dreamy feeling when one first wakes on a summer morning, with the twitter of birds in the air, and the fresh breeze coming in at the open window —when, lying lazily with eyes half shut, one sees as in a dream green boughs waving, or waters rippling in a golden light? It is a pleasure very near to sadness, bringing tears to one's eyes like a beautiful picture or poem. And is not that a Mother's gentle hand that undraws your curtains, and a Mother's sweet voice that summons you to rise? To rise and forget, in the bright sunlight, the ugly dreams that frightened you so when all was dark —to rise and enjoy another happy day, first kneeling to thank that unseen Friend, who sends you the beautiful sun?

Are these strange words from a writer of such tales as "Alice"? And is this a strange letter to find in a book of nonsense? It may be so. Some perhaps may blame me for thus mixing together things grave and gay; others may smile and think it odd that any one should speak of solemn things at all, except in church and on a Sunday: but I think —nay, I am sure —that some children will read this gently and lovingly, and in the spirit in which I have written it.

For I do not believe God means us thus to divide life into two halves —to wear a grave face on Sunday, and to think it out-of-place to even so much as mention Him on a week-day. Do you think He cares to see only kneeling figures, and to hear only tones of prayer —and that He does not also love to see the lambs leaping in the sunlight, and to hear the merry voices of the children, as they roll among the hay? Surely their innocent laughter is as sweet in His ears as the grandest anthem that ever rolled up from the "dim religious light" of some solemn cathedral?

And if I have written anything to add to those stores of innocent and healthy amusement that are laid up in books for the children I love so well, it is surely something I may hope to look back upon without shame and sorrow (as how much of life must then be recalled!) when

my

turn comes to walk through the valley of shadows.

This Easter sun will rise on you, dear child, feeling your "life in every limb," and eager to rush out into the fresh morning air —and many an Easter-day will come and go, before it finds you feeble and gray-headed, creeping wearily out to bask once more in the sunlight —but it is good, even now, to think sometimes of that great morning when the "Sun of Righteousness shall arise with healing in his wings."

Surely your gladness need not be the less for the thought that you will one day see a brighter dawn than this —when lovelier sights will meet your eyes than any waving trees or rippling waters —when angel-hands shall undraw your curtains, and sweeter tones than ever loving Mother breathed shall wake you to a new and glorious day —and when all the sadness, and the sin, that darkened life on this little earth, shall be forgotten like the dreams of a night that is past!

Your affectionate friend,

LEWIS CARROLL.

EASTER, 1876.

Inscribed to a dear Child:

in memory of golden summer hours

and whispers of a summer sea

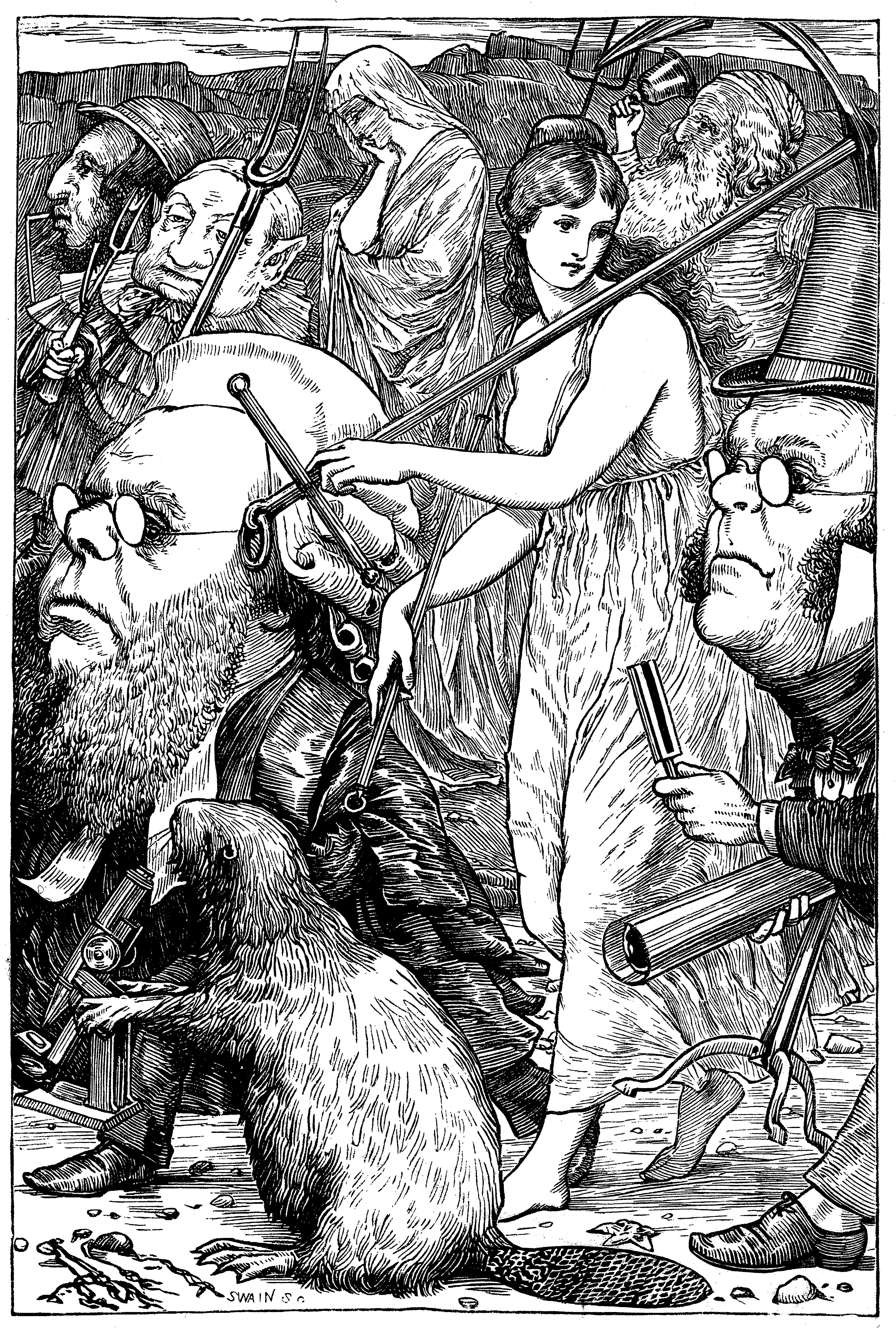

Girt with a boyish garb for a boyish task,

Eager she wields her spade: yet loves a well

Rest on a friendly knee, intent to ask

The tale he loves to tell.

Rude spirits of the seething outer strife,

Unmeet to read her pure and simple spright,

Deem, if you list, such hours a waste of life

Empty of all delight!

Chat on, sweet Maid, and rescue from annoy

Hearts that by wiser talk are unbeguiled.

Ah, happy he who owns that tenderest joy,

The heart-love of a child!

Away, fond thoughts, and vex my soul no more!

Work claims my wakeful nights, my busy days —

Albeit bright memories of that sunlit shore

Yet haunt my dreaming gaze!

PREFACE

If — and the thing is wildly possible — the charge of

writing nonsense were ever brought against the author of this brief

but instructive poem, it would be based, I feel convinced, on the

line (in p.4)

“Then the bowsprit got mixed with the rudder

sometimes.”

In view of this painful possibility, I will not (as I might)

appeal indignantly to my other writings as a proof that I am

incapable of such a deed: I will not (as I might) point to the

strong moral purpose of this poem itself, to the arithmetical

principles so cautiously inculcated in it, or to its noble

teachings in Natural History — I will take the more prosaic

course of simply explaining how it happened.

The Bellman, who was almost morbidly sensitive about

appearances, used to have the bowsprit unshipped once or twice a

week to be revarnished, and it more than once happened, when the

time came for replacing it, that no one on board could remember

which end of the ship it belonged to. They knew it was not of the

slightest use to appeal to the Bellman about it — he would

only refer to his Naval Code, and read out in pathetic tones

Admiralty Instructions which none of them had ever been able to

understand — so it generally ended in its being fastened on,

anyhow, across the rudder. The helmsman1 used to stand by with tears in his eyes;

he knew it was all wrong, but alas! Rule 42 of the Code,

“No one shall speak to the Man at the Helm,”

had been completed by the Bellman himself with the words

“and the Man at the Helm shall speak to no

one.“ So remonstrance was impossible, and no steering

could be done till the next varnishing day. During these

bewildering intervals the ship usually sailed backwards.

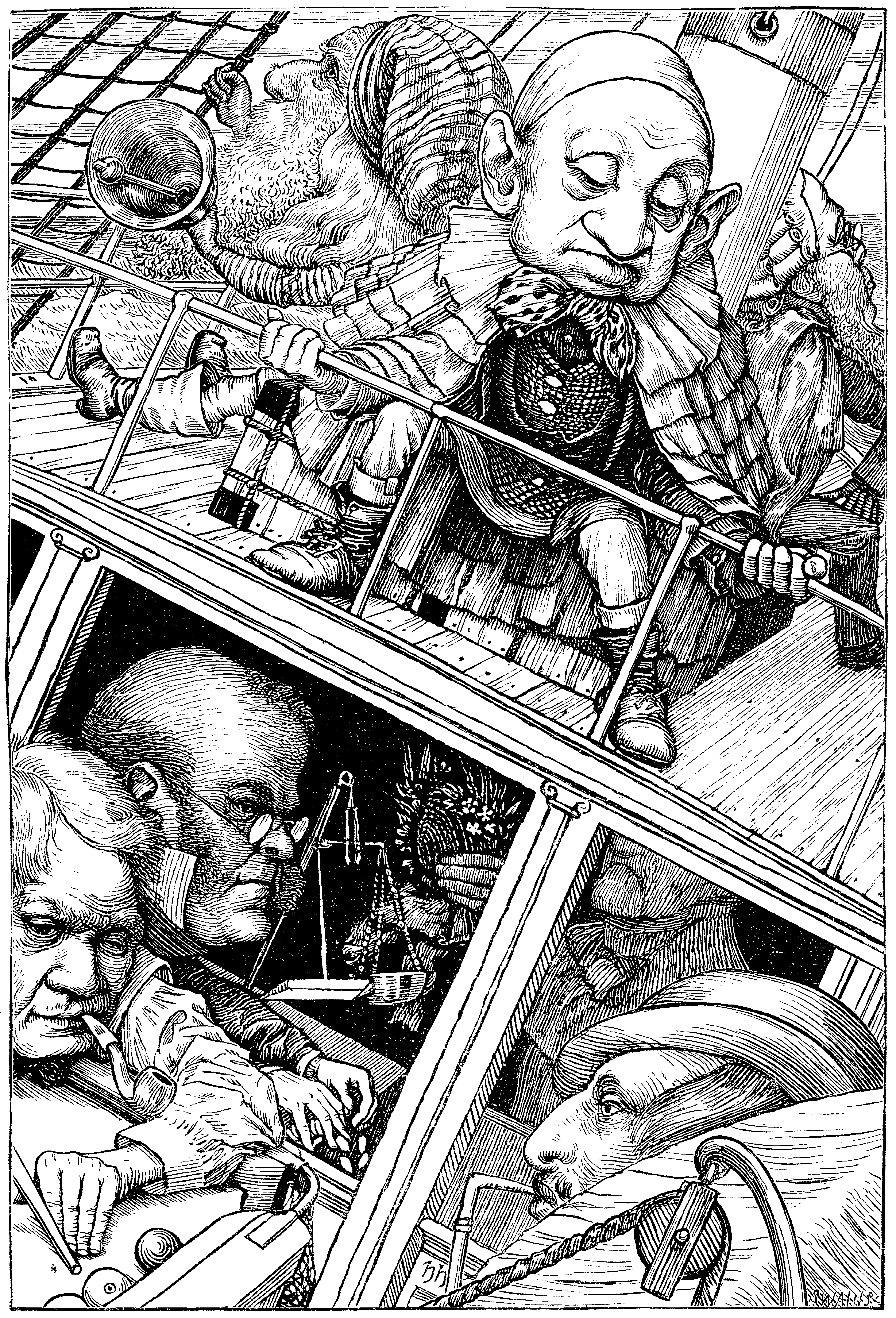

1 This office was usually

undertaken by the Boots, who found in it a refuge from the

Baker’s constant complaints about the insufficient blacking

of his three pairs of boots.

As this poem is to some extent connected with the lay of the

Jabberwock, let me take this opportunity of answering a question

that has often been asked me, how to pronounce “slithy

toves.” The “i” in “slithy” is long,

as in “writhe”; and “toves” is pronounced

so as to rhyme with “groves.” Again, the first

“o” in “borogoves” is pronounced like the

“o” in “borrow.” I have heard people try to

give it the sound of the “o” in “worry. Such is

Human Perversity.

This also seems a fitting occasion to notice the other hard

words in that poem. Humpty-Dumpty’s theory, of two meanings

packed into one word like a portmanteau, seems to me the right

explanation for all.

For instance, take the two words “fuming” and

“furious.” Make up your mind that you will say both

words, but leave it unsettled which you will say first. Now open

your mouth and speak. If your thoughts incline ever so little

towards “fuming,” you will say

“fuming-furious;” if they turn, by even a hair’s

breadth, towards “furious,” you will say

“furious-fuming;” but if you have the rarest of gifts,

a perfectly balanced mind, you will say “frumious.”

Supposing that, when Pistol uttered the well-known

words —

“Under which king, Bezonian? Speak or

die!”

Justice Shallow had felt certain that it was either William or

Richard, but had not been able to settle which, so that he could

not possibly say either name before the other, can it be doubted

that, rather than die, he would have gasped out

“Rilchiam!”

Fit the First

THE LANDING

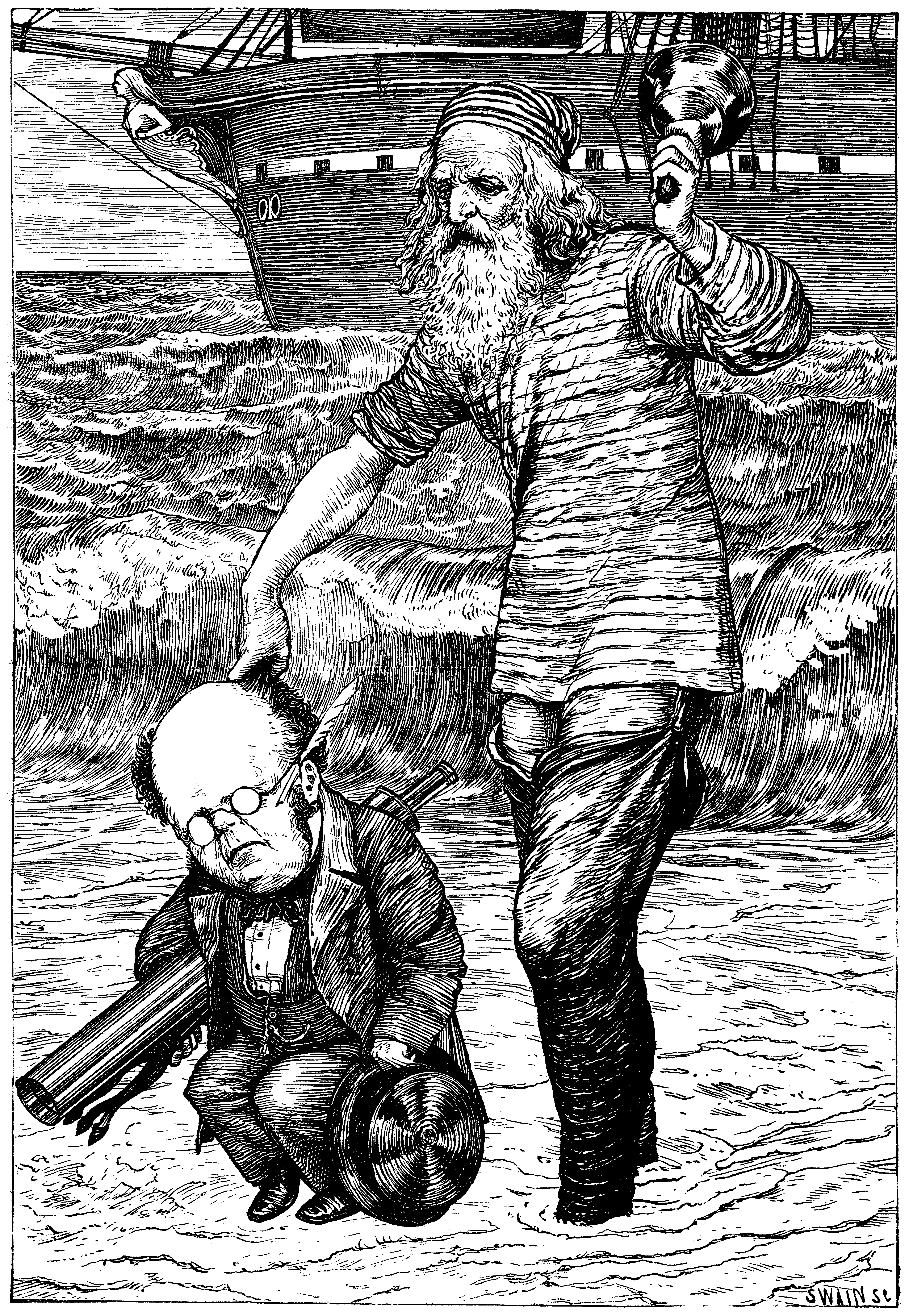

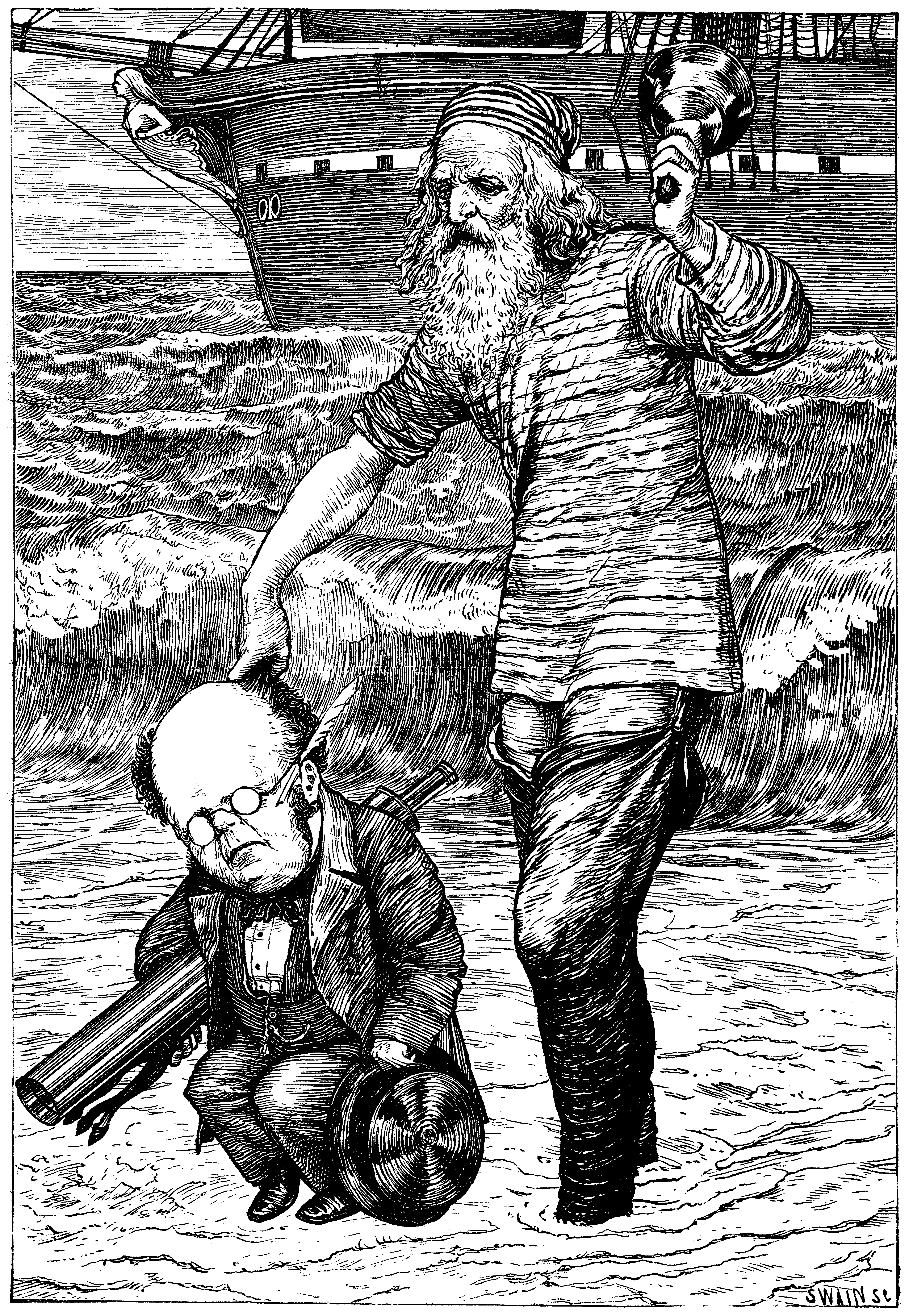

001 “Just the place for a Snark!” the Bellman cried,

002

As he landed his crew with care;

003

Supporting each man on the top of the tide

004

By a finger entwined in his hair.

005 “Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice:

006

That alone should encourage the crew.

007

Just the place for a Snark! I have said it thrice:

008

What I tell you three times is true.”

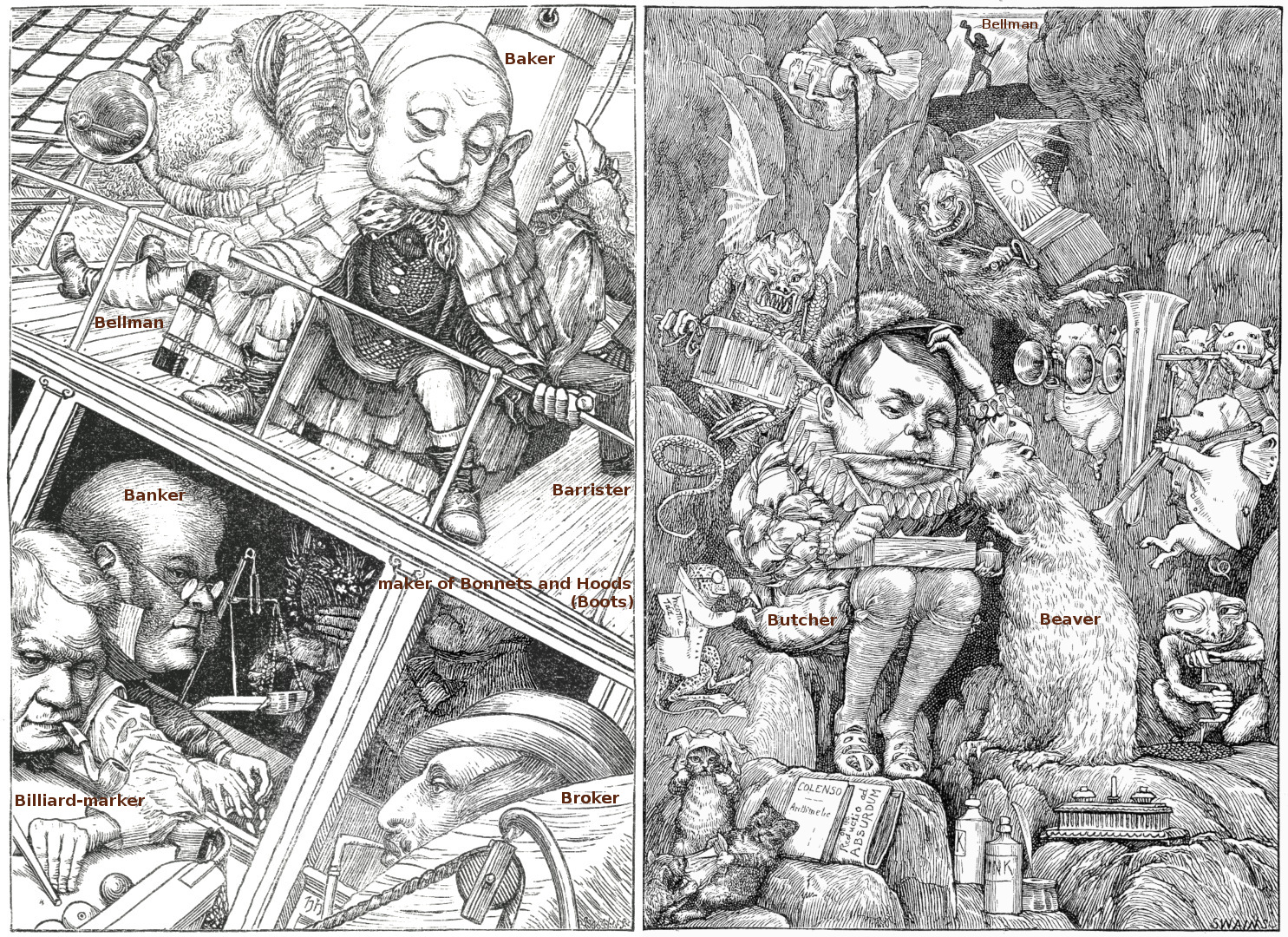

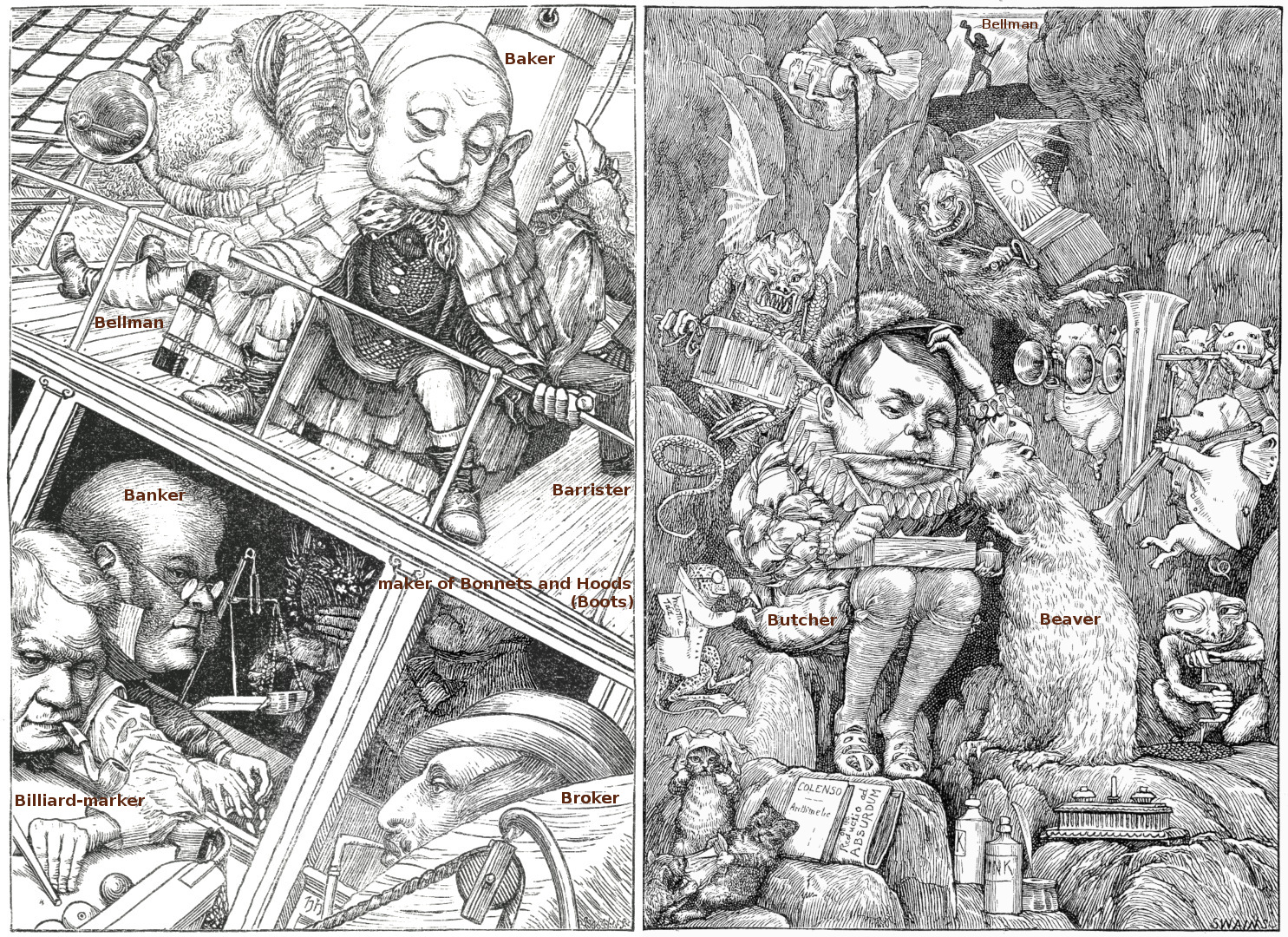

009 The crew was complete: it included a Boots —

010

A maker of Bonnets and Hoods —

011

A Barrister, brought to arrange their disputes —

012

And a Broker, to value their goods.

013 A Billiard-marker, whose skill was immense,

014

Might perhaps have won more than his share —

015

But a Banker, engaged at enormous expense,

016

Had the whole of their cash in his care.

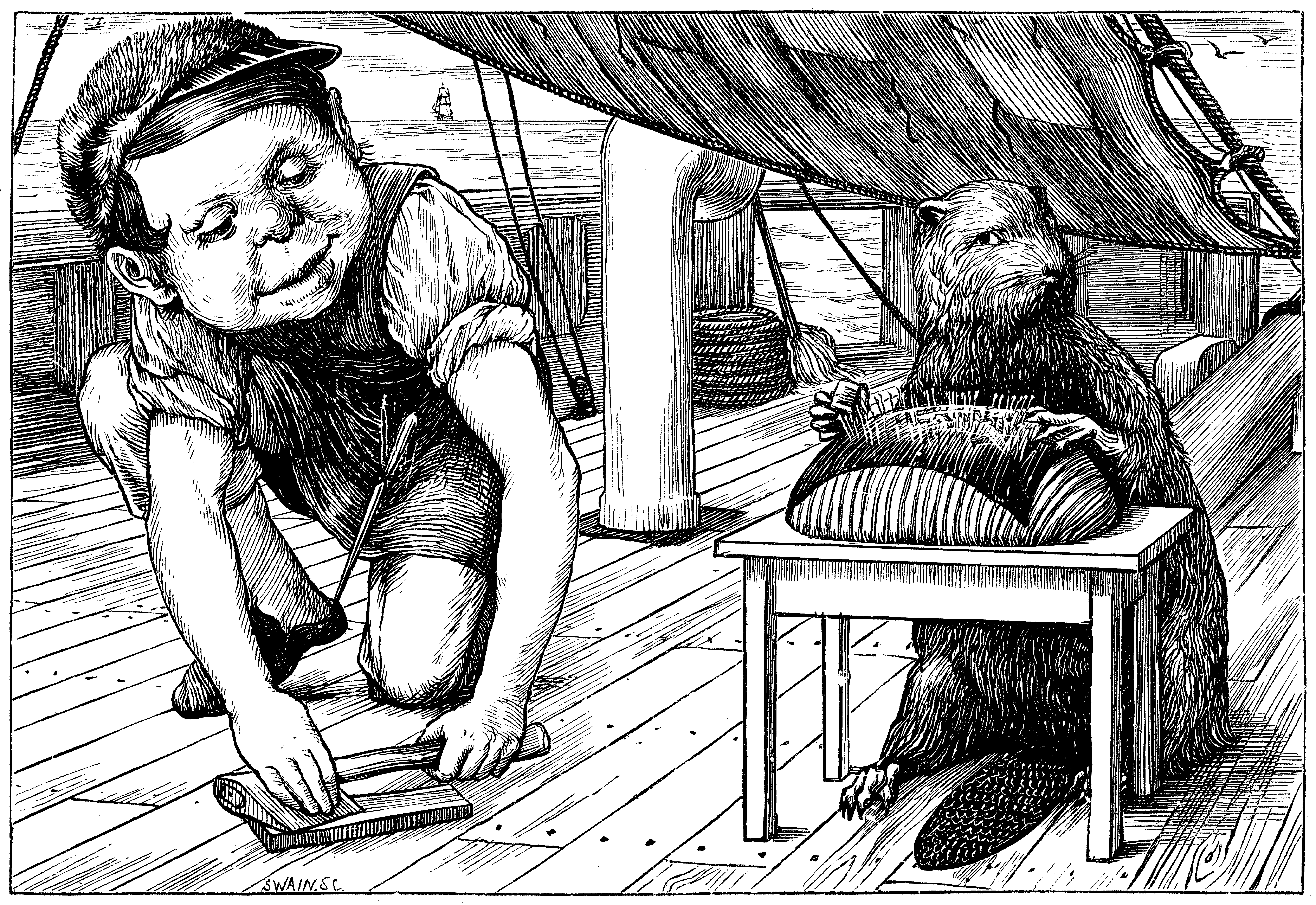

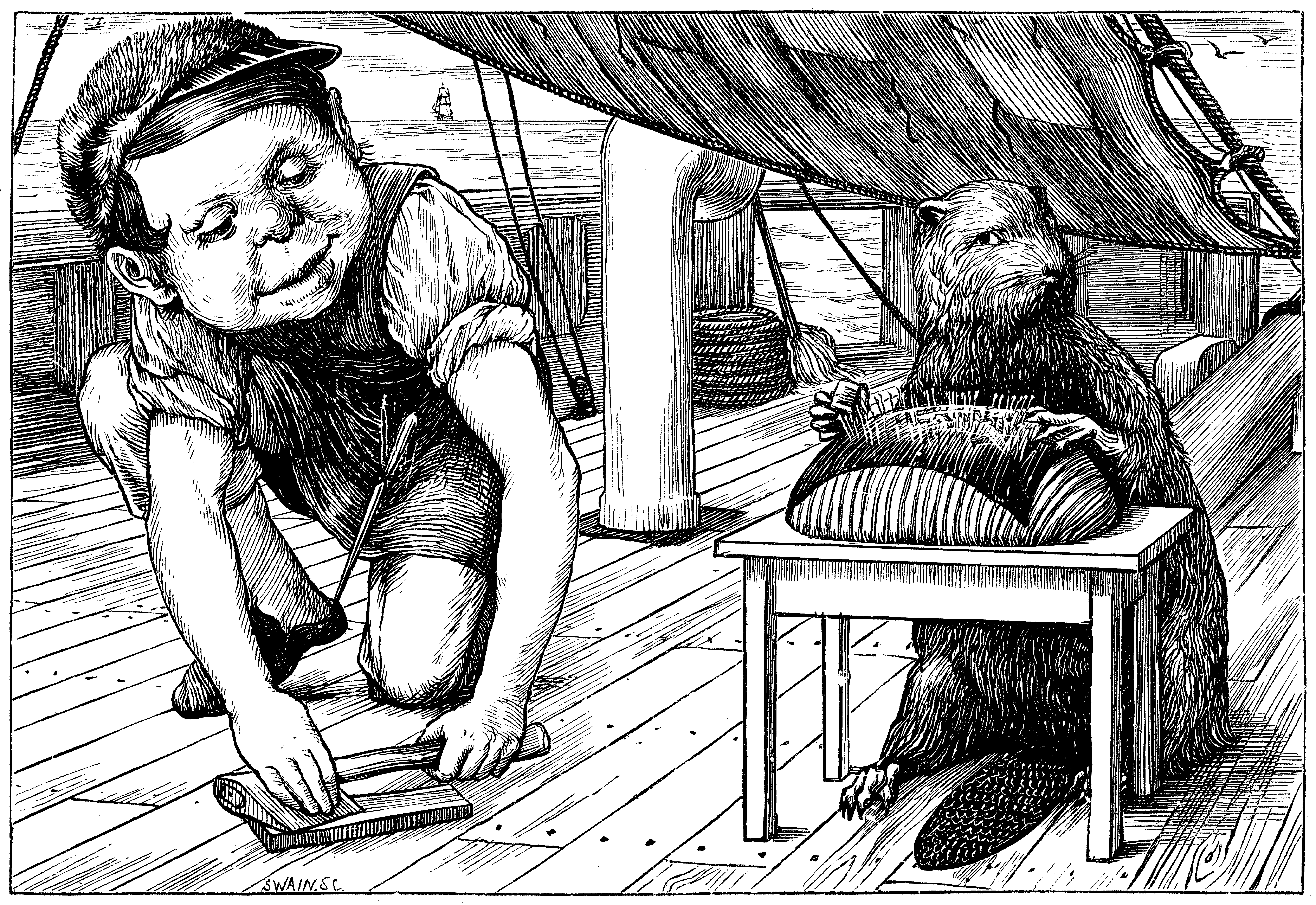

017 There was also a Beaver, that paced on the deck,

018

Or would sit making lace in the bow:

019

And had often (the Bellman said) saved them from wreck,

020

Though none of the sailors knew how.

021 There was one who was famed for the number of things

022

He forgot when he entered the ship:

023

His umbrella, his watch, all his jewels and rings,

024

And the clothes he had bought for the trip.

025 He had forty-two boxes, all carefully packed,

026

With his name painted clearly on each:

027

But, since he omitted to mention the fact,

028

They were all left behind on the beach.

029 The loss of his clothes hardly mattered, because

030

He had seven coats on when he came,

031

With three pairs of boots —but the worst of it was,

032

He had wholly forgotten his name.

033 He would answer to “Hi!” or to any loud cry,

034

Such as “Fry me!” or “Fritter my wig!”

035

To “What-you-may-call-um!” or “What-was-his-name!”

036

But especially “Thing-um-a-jig!”

037 While, for those who preferred a more forcible word,

038

He had different names from these:

039

His intimate friends called him “Candle-ends,”

040

And his enemies “Toasted-cheese.”

041 “His form is ungainly —his intellect small —”

042

(So the Bellman would often remark)

043

“But his courage is perfect! And that, after all,

044

Is the thing that one needs with a Snark.”

045 He would joke with hyenas, returning their stare

046

With an impudent wag of the head:

047

And he once went a walk, paw-in-paw, with a bear,

048

“Just to keep up its spirits,” he said.

049 He came as a Baker: but owned, when too late —

050

And it drove the poor Bellman half-mad —

051

He could only bake Bridecake —for which, I may state,

052

No materials were to be had.

053 The last of the crew needs especial remark,

054

Though he looked an incredible dunce:

055

He had just one idea —but, that one being “Snark,”

056

The good Bellman engaged him at once.

057 He came as a Butcher: but gravely declared,

058

When the ship had been sailing a week,

059

He could only kill Beavers. The Bellman looked scared,

060

And was almost too frightened to speak:

061 But at length he explained, in a tremulous tone,

062

There was only one Beaver on board;

063

And that was a tame one he had of his own,

064

Whose death would be deeply deplored.

065 The Beaver, who happened to hear the remark,

066

Protested, with tears in its eyes,

067

That not even the rapture of hunting the Snark

068

Could atone for that dismal surprise!

069 It strongly advised that the Butcher should be

070

Conveyed in a separate ship:

071

But the Bellman declared that would never agree

072

With the plans he had made for the trip:

073 Navigation was always a difficult art,

074

Though with only one ship and one bell:

075

And he feared he must really decline, for his part,

076

Undertaking another as well.

077 The Beaver’s best course was, no doubt, to procure

078

A second-hand dagger-proof coat —

079

So the Baker advised it — and next, to insure

080

Its life in some Office of note:

081 This the Banker suggested, and offered for hire

082

(On moderate terms), or for sale,

083

Two excellent Policies, one Against Fire,

084

And one Against Damage From Hail.

085 Yet still, ever after that sorrowful day,

086

Whenever the Butcher was by,

087

The Beaver kept looking the opposite way,

088

And appeared unaccountably shy.

Fit the Second

THE BELLMAN’S SPEECH

089 The Bellman himself they all praised to the skies —

090

Such a carriage, such ease and such grace!

091

Such solemnity, too! One could see he was wise,

092

The moment one looked in his face!

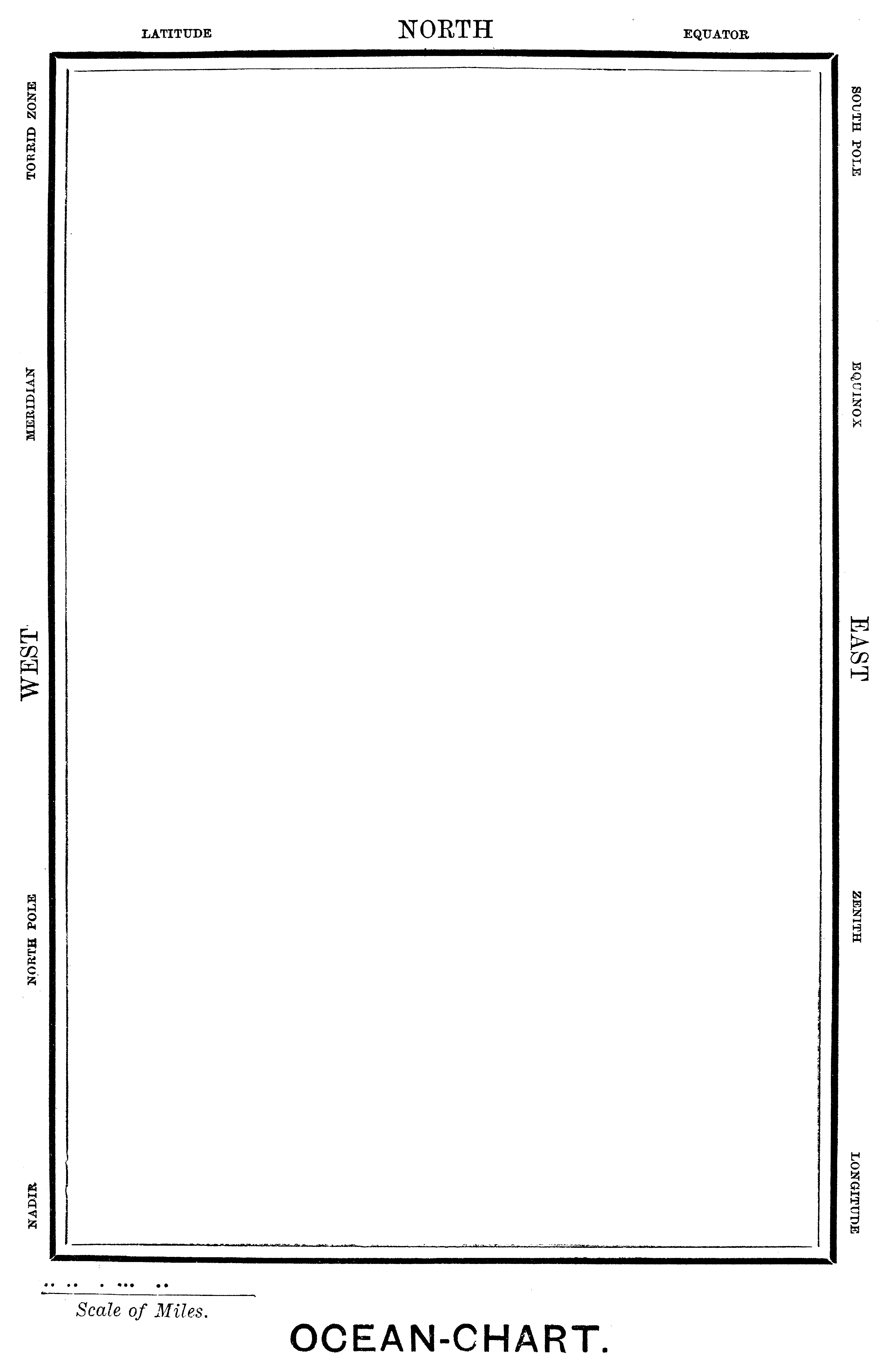

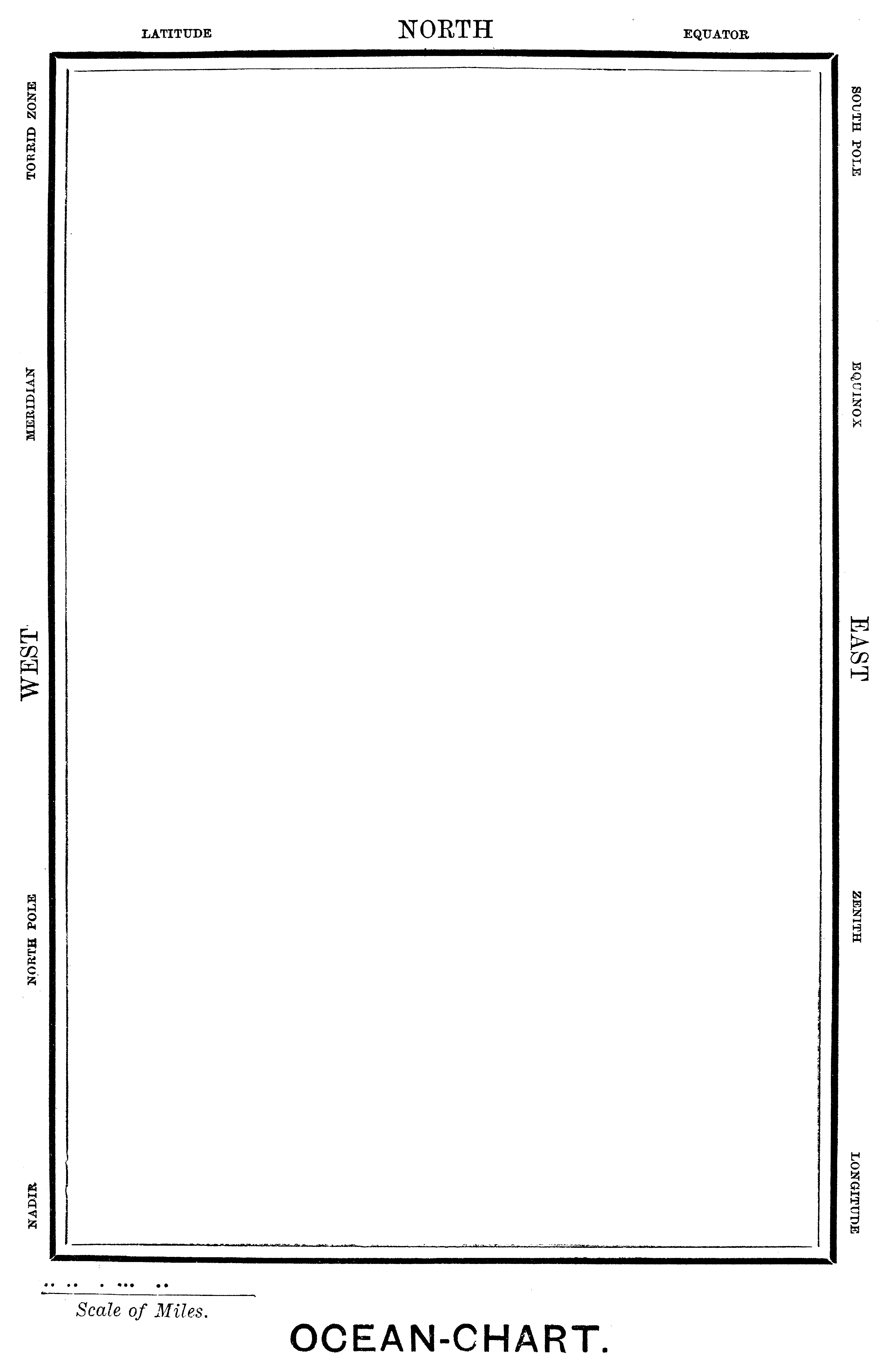

093 He had bought a large map representing the sea,

094

Without the least vestige of land:

095

And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be

096

A map they could all understand.

097 “What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators,

098

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?”

099

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

100

“They are merely conventional signs!

101 “Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

102

But we’ve got our brave Captain to thank:

103

(So the crew would protest) “that he’s bought us the best —

104

A perfect and absolute blank!”

105 This was charming, no doubt; but they shortly found out

106

That the Captain they trusted so well

107

Had only one notion for crossing the ocean,

108

And that was to tingle his bell.

109 He was thoughtful and grave —but the orders he gave

110

Were enough to bewilder a crew.

111

When he cried “Steer to starboard, but keep her head larboard!”

112

What on earth was the helmsman to do?

113 Then the bowsprit got mixed with the rudder sometimes:

114

A thing, as the Bellman remarked,

115

That frequently happens in tropical climes,

116

When a vessel is, so to speak, “snarked.”

117 But the principal failing occurred in the sailing,

118

And the Bellman, perplexed and distressed,

119

Said he had hoped, at least, when the wind blew due East,

120

That the ship would not travel due West!

121 But the danger was past —they had landed at last,

122

With their boxes, portmanteaus, and bags:

123

Yet at first sight the crew were not pleased with the view,

124

Which consisted of chasms and crags.

125 The Bellman perceived that their spirits were low,

126

And repeated in musical tone

127

Some jokes he had kept for a season of woe —

128

But the crew would do nothing but groan.

129 He served out some grog with a liberal hand,

130

And bade them sit down on the beach:

131

And they could not but own that their Captain looked grand,

132

As he stood and delivered his speech.

133 “Friends, Romans, and countrymen, lend me your ears!”

134

(They were all of them fond of quotations:

135

So they drank to his health, and they gave him three cheers,

136

While he served out additional rations).

137 “We have sailed many months, we have sailed many weeks,

138

(Four weeks to the month you may mark),

139

But never as yet (’tis your Captain who speaks)

140

Have we caught the least glimpse of a Snark!

141 “We have sailed many weeks, we have sailed many days,

142

(Seven days to the week I allow),

143

But a Snark, on the which we might lovingly gaze,

144

We have never beheld till now!

145 “Come, listen, my men, while I tell you again

146

The five unmistakable marks

147

By which you may know, wheresoever you go,

148

The warranted genuine Snarks.

149 “Let us take them in order. The first is the taste,

150

Which is meagre and hollow, but crisp:

151

Like a coat that is rather too tight in the waist,

152

With a flavour of Will-o’-the-wisp.

153 “Its habit of getting up late you’ll agree

154

That it carries too far, when I say

155

That it frequently breakfasts at five-o’clock tea,

156

And dines on the following day.

157 “The third is its slowness in taking a jest.

158

Should you happen to venture on one,

159

It will sigh like a thing that is deeply distressed:

160

And it always looks grave at a pun.

161 “The fourth is its fondness for bathing-machines,

162

Which it constantly carries about,

163

And believes that they add to the beauty of scenes —

164

A sentiment open to doubt.

165 “The fifth is ambition. It next will be right

166

To describe each particular batch:

167

Distinguishing those that have feathers, and bite,

168

And those that have whiskers, and scratch.

169 “For, although common Snarks do no manner of harm,

170

Yet, I feel it my duty to say,

171

Some are Boojums —” The Bellman broke off in alarm,

172

For the Baker had fainted away.

Fit the Third

THE BAKER’S TALE

173 They roused him with muffins —they roused him with ice —

174

They roused him with mustard and cress —

175

They roused him with jam and judicious advice —

176

They set him conundrums to guess.

177 When at length he sat up and was able to speak,

178

His sad story he offered to tell;

179

And the Bellman cried “Silence! Not even a shriek!”

180

And excitedly tingled his bell.

181 There was silence supreme! Not a shriek, not a scream,

182

Scarcely even a howl or a groan,

183

As the man they called “Ho!” told his story of woe

184

In an antediluvian tone.

185 “My father and mother were honest, though poor —”

186

“Skip all that!” cried the Bellman in haste.

187

“If it once becomes dark, there’s no chance of a Snark —

188

We have hardly a minute to waste!”

189 “I skip forty years,” said the Baker, in tears,

190

“And proceed without further remark

191

To the day when you took me aboard of your ship

192

To help you in hunting the Snark.

193 “A dear uncle of mine (after whom I was named)

194

Remarked, when I bade him farewell —”

195

“Oh, skip your dear uncle!” the Bellman exclaimed,

196

As he angrily tingled his bell.

197 “He remarked to me then,” said that mildest of men,

198

“ ‘If your Snark be a Snark, that is right:

199

Fetch it home by all means —you may serve it with greens,

200

And it’s handy for striking a light.

201 “ ‘You may seek it with thimbles —and seek it with care;

202

You may hunt it with forks and hope;

203

You may threaten its life with a railway-share;

204

You may charm it with smiles and soap —’ ”

205 (“That’s exactly the method,” the Bellman bold

206

In a hasty parenthesis cried,

207

“That’s exactly the way I have always been told

208

That the capture of Snarks should be tried!”)

209 “ ‘But oh, beamish nephew, beware of the day,

210

If your Snark be a Boojum! For then

211

You will softly and suddenly vanish away,

212

And never be met with again!’

213 “It is this, it is this that oppresses my soul,

214

When I think of my uncle’s last words:

215

And my heart is like nothing so much as a bowl

216

Brimming over with quivering curds!

217 “It is this, it is this —” “We have had that before!”

218

The Bellman indignantly said.

219

And the Baker replied “Let me say it once more.

220

It is this, it is this that I dread!

221 “I engage with the Snark —every night after dark —

222

In a dreamy delirious fight:

223

I serve it with greens in those shadowy scenes,

224

And I use it for striking a light:

225 “But if ever I meet with a Boojum, that day,

226

In a moment (of this I am sure),

227

I shall softly and suddenly vanish away —

228

And the notion I cannot endure!”

Fit the fourth

THE HUNTING

229 The Bellman looked uffish, and wrinkled his brow.

230

“If only you’d spoken before!

231

It’s excessively awkward to mention it now,

232

With the Snark, so to speak, at the door!

233 “We should all of us grieve, as you well may believe,

234

If you never were met with again —

235

But surely, my man, when the voyage began,

236

You might have suggested it then?

237 “It’s excessively awkward to mention it now —

238

As I think I’ve already remarked.”

239

And the man they called “Hi!” replied, with a sigh,

240

“I informed you the day we embarked.

241 “You may charge me with murder —or want of sense —

242

(We are all of us weak at times):

243

But the slightest approach to a false pretence

244

Was never among my crimes!

245 “I said it in Hebrew —I said it in Dutch —

246

I said it in German and Greek:

247

But I wholly forgot (and it vexes me much)

248

That English is what you speak!”

249 “’Tis a pitiful tale,” said the Bellman, whose face

250

Had grown longer at every word:

251

“But, now that you’ve stated the whole of your case,

252

More debate would be simply absurd.

253 “The rest of my speech” (he explained to his men)

254

“You shall hear when I’ve leisure to speak it.

255

But the Snark is at hand, let me tell you again!

256

’Tis your glorious duty to seek it!

257 “To seek it with thimbles, to seek it with care;

258

To pursue it with forks and hope;

259

To threaten its life with a railway-share;

260

To charm it with smiles and soap!

261 “For the Snark’s a peculiar creature, that won’t

262

Be caught in a commonplace way.

263

Do all that you know, and try all that you don’t:

264

Not a chance must be wasted to-day!

265 “For England expects —I forbear to proceed:

266

’Tis a maxim tremendous, but trite:

267

And you’d best be unpacking the things that you need

268

To rig yourselves out for the fight.”

269 Then the Banker endorsed a blank cheque (which he crossed),

270

And changed his loose silver for notes.

271

The Baker with care combed his whiskers and hair,

272

And shook the dust out of his coats.

273 The Boots and the Broker were sharpening a spade —

274

Each working the grindstone in turn:

275

But the Beaver went on making lace, and displayed

276

No interest in the concern:

277 Though the Barrister tried to appeal to its pride,

278

And vainly proceeded to cite

279

A number of cases, in which making laces

280

Had been proved an infringement of right.

281 The maker of Bonnets ferociously planned

282

A novel arrangement of bows:

283

While the Billiard-marker with quivering hand

284

Was chalking the tip of his nose.

285 But the Butcher turned nervous, and dressed himself fine,

286

With yellow kid gloves and a ruff —

287

Said he felt it exactly like going to dine,

288

Which the Bellman declared was all “stuff.”

289 “Introduce me, now there’s a good fellow,” he said,

290

“If we happen to meet it together!”

291

And the Bellman, sagaciously nodding his head,

292

Said “That must depend on the weather.”

293 The Beaver went simply galumphing about,

294

At seeing the Butcher so shy:

295

And even the Baker, though stupid and stout,

296

Made an effort to wink with one eye.

297 “Be a man!” said the Bellman in wrath, as he heard

298

The Butcher beginning to sob.

299

“Should we meet with a Jubjub, that desperate bird,

300

We shall need all our strength for the job!”

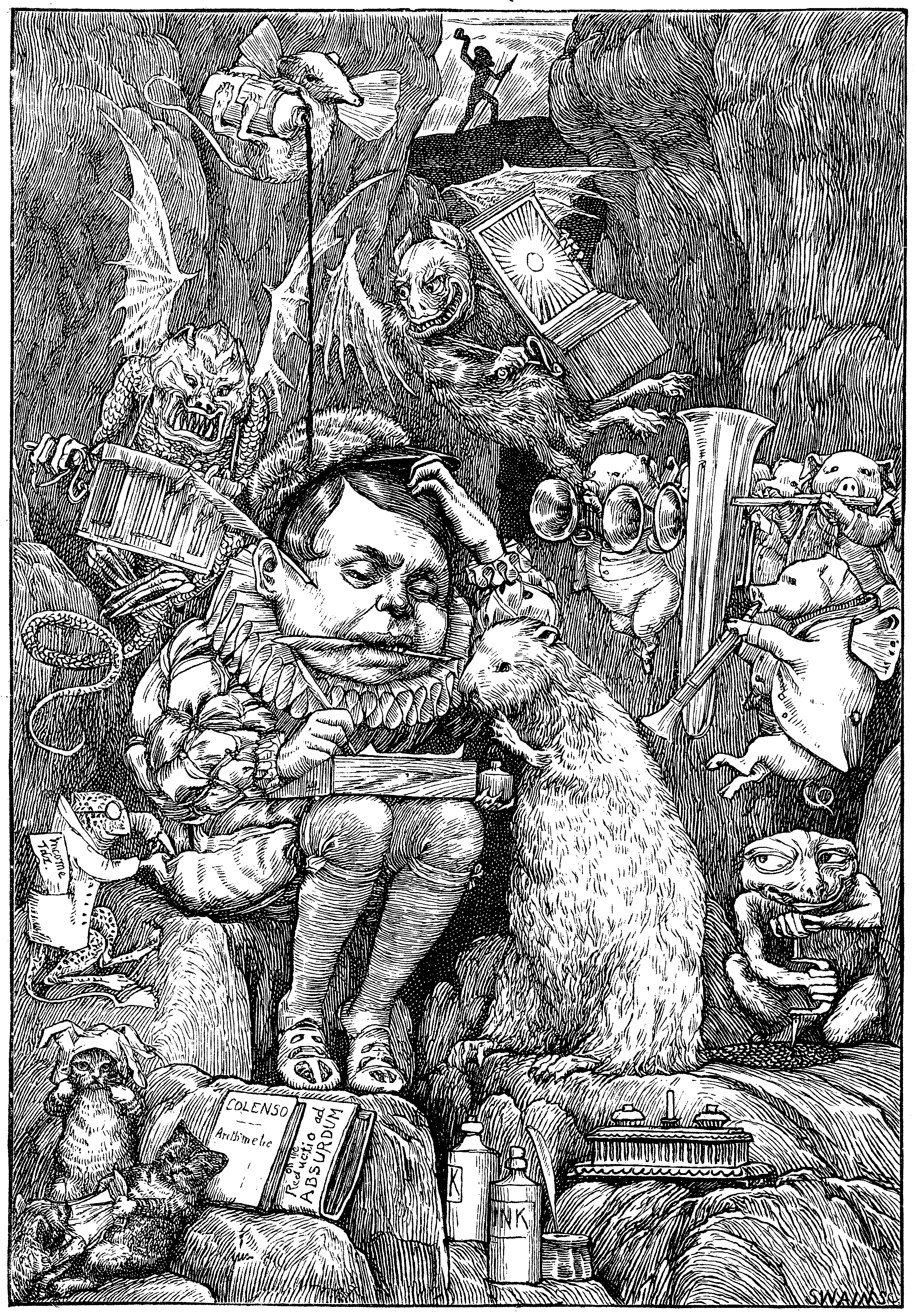

Fit the Fifth

THE BEAVER’S LESSON

301 They sought it with thimbles, they sought it with care;

302

They pursued it with forks and hope;

303

They threatened its life with a railway-share;

304

They charmed it with smiles and soap.

305 Then the Butcher contrived an ingenious plan

306

For making a separate sally;

307

And had fixed on a spot unfrequented by man,

308

A dismal and desolate valley.

309 But the very same plan to the Beaver occurred:

310

It had chosen the very same place:

311

Yet neither betrayed, by a sign or a word,

312

The disgust that appeared in his face.

313 Each thought he was thinking of nothing but “Snark”

314

And the glorious work of the day;

315

And each tried to pretend that he did not remark

316

That the other was going that way.

317 But the valley grew narrow and narrower still,

318

And the evening got darker and colder,

319

Till (merely from nervousness, not from goodwill)

320

They marched along shoulder to shoulder.

321 Then a scream, shrill and high, rent the shuddering sky,

322

And they knew that some danger was near:

323

The Beaver turned pale to the tip of its tail,

324

And even the Butcher felt queer.

325 He thought of his childhood, left far far behind —

326

That blissful and innocent state —

327

The sound so exactly recalled to his mind

328

A pencil that squeaks on a slate!

329 “’Tis the voice of the Jubjub!” he suddenly cried.

330

(This man, that they used to call “Dunce.”)

331

“As the Bellman would tell you,” he added with pride,

332

“I have uttered that sentiment once.

333 “’Tis the note of the Jubjub! Keep count, I entreat;

334

You will find I have told it you twice.

335

’Tis the song of the Jubjub! The proof is complete,

336

If only I’ve stated it thrice.”

337 The Beaver had counted with scrupulous care,

338

Attending to every word:

339

But it fairly lost heart, and outgrabe in despair,

340

When the third repetition occurred.

341 It felt that, in spite of all possible pains,

342

It had somehow contrived to lose count,

343

And the only thing now was to rack its poor brains

344

By reckoning up the amount.

345 “Two added to one —if that could but be done,”

346

It said, “with one’s fingers and thumbs!”

347

Recollecting with tears how, in earlier years,

348

It had taken no pains with its sums.

349 “The thing can be done,” said the Butcher, “I think.

350

The thing must be done, I am sure.

351

The thing shall be done! Bring me paper and ink,

352

The best there is time to procure.”

353 The Beaver brought paper,portfolio, pens,

354

And ink in unfailing supplies:

355

While strange creepy creatures came out of their dens,

356

And watched them with wondering eyes.

357 So engrossed was the Butcher, he heeded them not,

358

As he wrote with a pen in each hand,

359

And explained all the while in a popular style

360

Which the Beaver could well understand.

361 “Taking Three as the subject to reason about —

362

A convenient number to state —

363

We add Seven, and Ten, and then multiply out

364

By One Thousand diminished by Eight.

365 “The result we proceed to divide, as you see,

366

By Nine Hundred and Ninety Two:

367

Then subtract Seventeen, and the answer must be

368

Exactly and perfectly true.

369 “The method employed I would gladly explain,

370

While I have it so clear in my head,

371

If I had but the time and you had but the brain —

372

But much yet remains to be said.

373 “In one moment I’ve seen what has hitherto been

374

Enveloped in absolute mystery,

375

And without extra charge I will give you at large

376

A Lesson in Natural History.”

377 In his genial way he proceeded to say

378

(Forgetting all laws of propriety,

379

And that giving instruction, without introduction,

380

Would have caused quite a thrill in Society),

381 “As to temper the Jubjub’s a desperate bird,

382

Since it lives in perpetual passion:

383

Its taste in costume is entirely absurd —

384

It is ages ahead of the fashion:

385 “But it knows any friend it has met once before:

386

It never will look at a bribe:

387

And in charity-meetings it stands at the door,

388

And collects —though it does not subscribe.

389 “ Its flavour when cooked is more exquisite far

390

Than mutton, or oysters, or eggs:

391

(Some think it keeps best in an ivory jar,

392

And some, in mahogany kegs:)

393 “You boil it in sawdust: you salt it in glue:

394

You condense it with locusts and tape:

395

Still keeping one principal object in view —

396

To preserve its symmetrical shape.”

397 The Butcher would gladly have talked till next day,

398

But he felt that the lesson must end,

399

And he wept with delight in attempting to say

400

He considered the Beaver his friend.

401 While the Beaver confessed, with affectionate looks

402

More eloquent even than tears,

403

It had learned in ten minutes far more than all books

404

Would have taught it in seventy years.

405 They returned hand-in-hand, and the Bellman, unmanned

406

(For a moment) with noble emotion,

407

Said “This amply repays all the wearisome days

408

We have spent on the billowy ocean!”

409 Such friends, as the Beaver and Butcher became,

410

Have seldom if ever been known;

411

In winter or summer, ’twas always the same —

412

You could never meet either alone.

413 And when quarrels arose —as one frequently finds

414

Quarrels will, spite of every endeavour —

415

The song of the Jubjub recurred to their minds,

416

And cemented their friendship for ever!

Fit the Sixth

417 They sought it with thimbles, they sought it with care;

418

They pursued it with forks and hope;

419

They threatened its life with a railway-share;

420

They charmed it with smiles and soap.

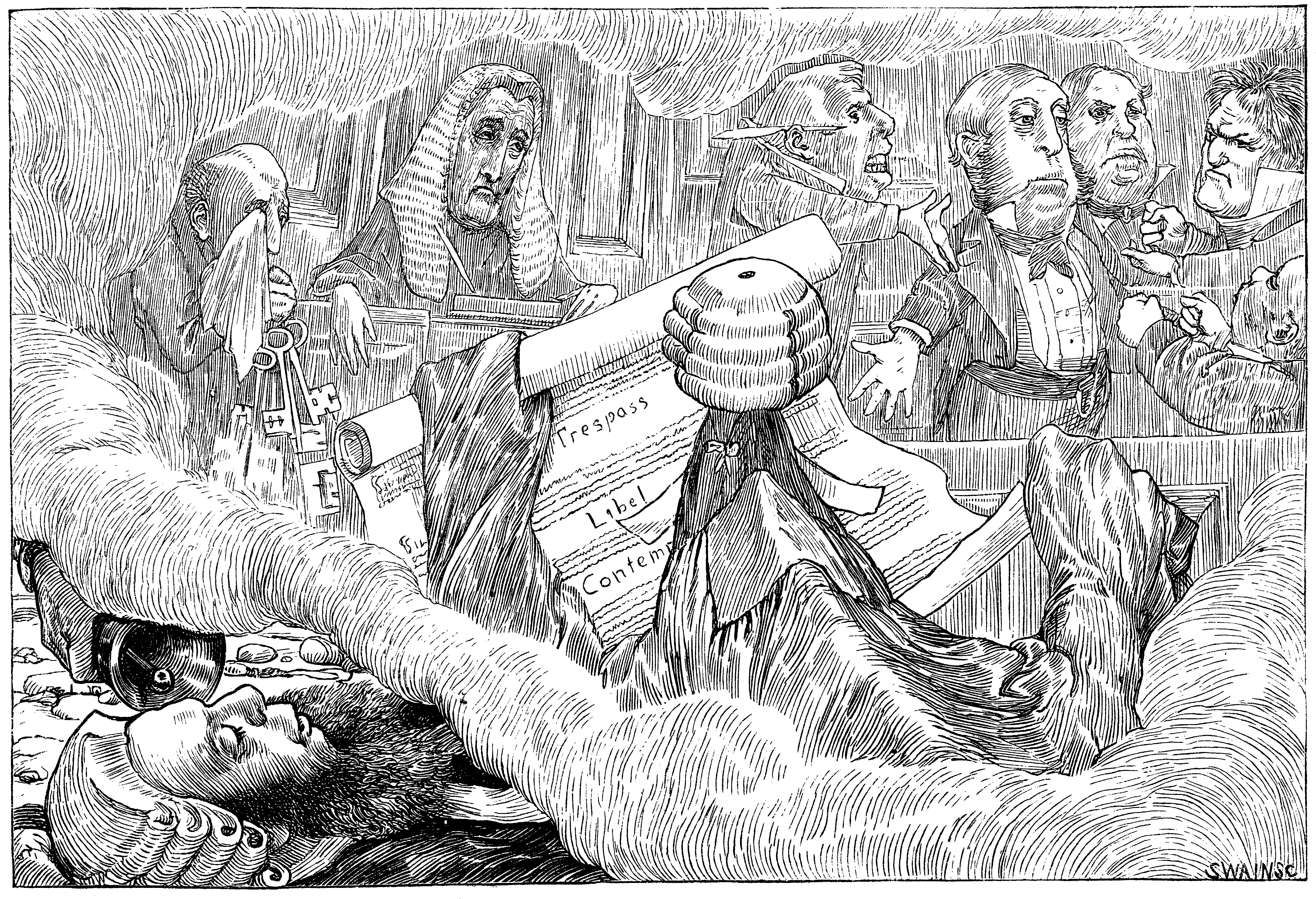

421 But the Barrister, weary of proving in vain

422

That the Beaver’s lace-making was wrong,

423

Fell asleep, and in dreams saw the creature quite plain

424

That his fancy had dwelt on so long.

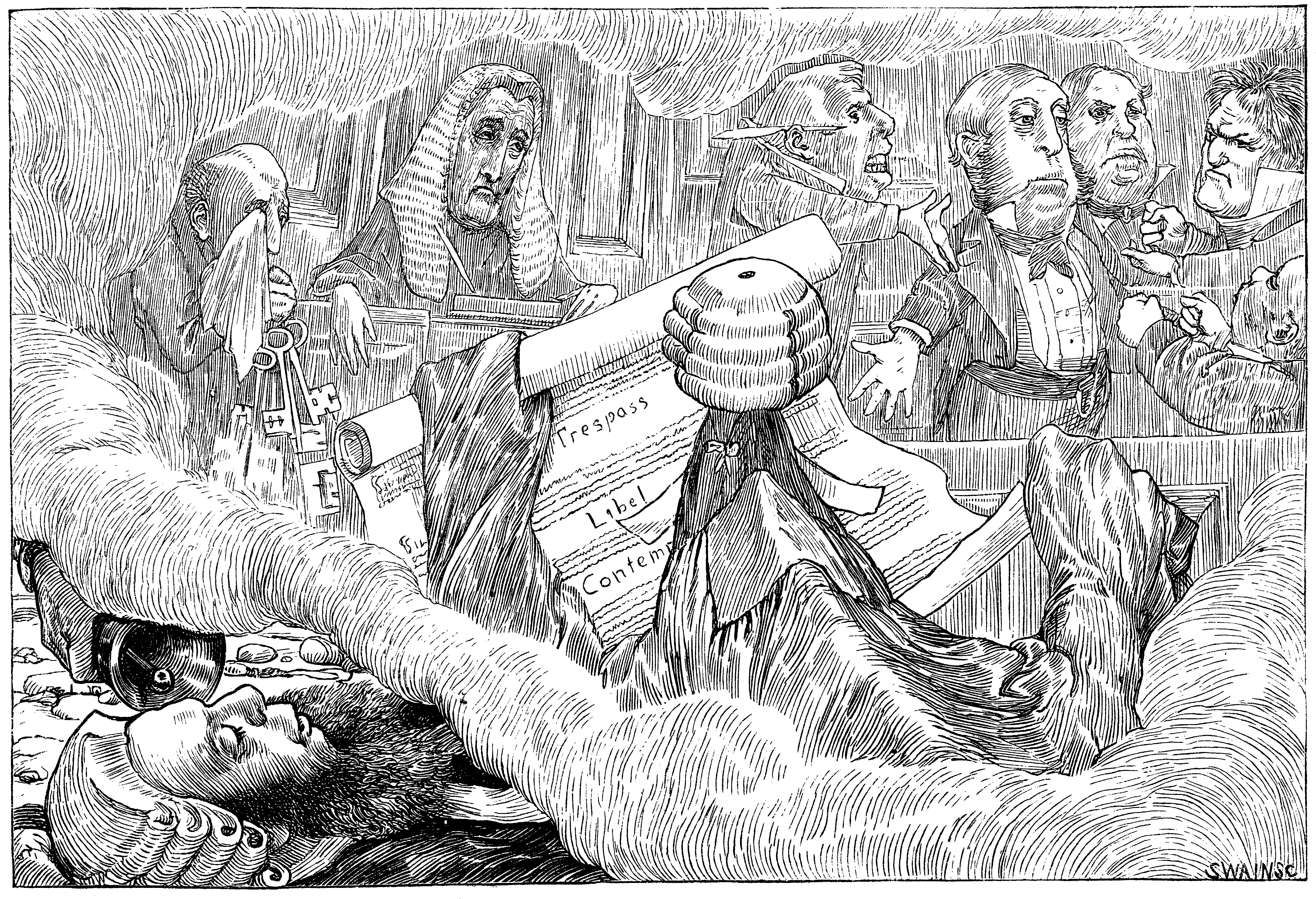

425 He dreamed that he stood in a shadowy Court,

426

Where the Snark, with a glass in its eye,

427

Dressed in gown, bands, and wig, was defending a pig

428

On the charge of deserting its sty.

429 The Witnesses proved, without error or flaw,

430

That the sty was deserted when found:

431

And the Judge kept explaining the state of the law

432

In a soft under-current of sound.

433 The indictment had never been clearly expressed,

434

And it seemed that the Snark had begun,

435

And had spoken three hours, before any one guessed

436

What the pig was supposed to have done.

437 The Jury had each formed a different view

438

(Long before the indictment was read),

439

And they all spoke at once, so that none of them knew

440

One word that the others had said.

441 “You must know — —” said the Judge: but the Snark exclaimed “Fudge!”

442

That statute is obsolete quite!

443

Let me tell you, my friends, the whole question depends

444

On an ancient manorial right.

445 “In the matter of Treason the pig would appear

446

To have aided, but scarcely abetted:

447

While the charge of Insolvency fails, it is clear,

448

If you grant the plea ‘never indebted.’

449 “The fact of Desertion I will not dispute;

450

But its guilt, as I trust, is removed

451

(So far as related to the costs of this suit)

452

By the Alibi which has been proved.

453 “My poor client’s fate now depends on your votes.”

454

Here the speaker sat down in his place,

455

And directed the Judge to refer to his notes

456

And briefly to sum up the case.

457 But the Judge said he never had summed up before;

458

So the Snark undertook it instead,

459

And summed it so well that it came to far more

460

Than the Witnesses ever had said!

461 When the verdict was called for, the Jury declined,

462

As the word was so puzzling to spell;

463

But they ventured to hope that the Snark wouldn’t mind

464

Undertaking that duty as well.

465 So the Snark found the verdict, although, as it owned,

466

It was spent with the toils of the day:

467

When it said the word “GUILTY!” the Jury all groaned,

468

And some of them fainted away.

469 Then the Snark pronounced sentence, the Judge being quite

470

Too nervous to utter a word:

471

When it rose to its feet, there was silence like night,

472

And the fall of a pin might be heard.

473 “Transportation for life”; was the sentence it gave,

474

“And then to be fined forty pound.”

475

The Jury all cheered, though the Judge said he feared

476

That the phrase was not legally sound.

477 But their wild exultation was suddenly checked

478

When the jailer informed them, with tears,

479

Such a sentence would have not the slightest effect,

480

As the pig had been dead for some years.

481 The Judge left the Court, looking deeply disgusted:

482

But the Snark, though a little aghast,

483

As the lawyer to whom the defense was entrusted,

484

Went bellowing on to the last.

485 Thus the Barrister dreamed, while the bellowing seemed

486

To grow every moment more clear:

487

Till he woke to the knell of a furious bell,

488

Which the Bellman rang close at his ear.

Fit the Seventh

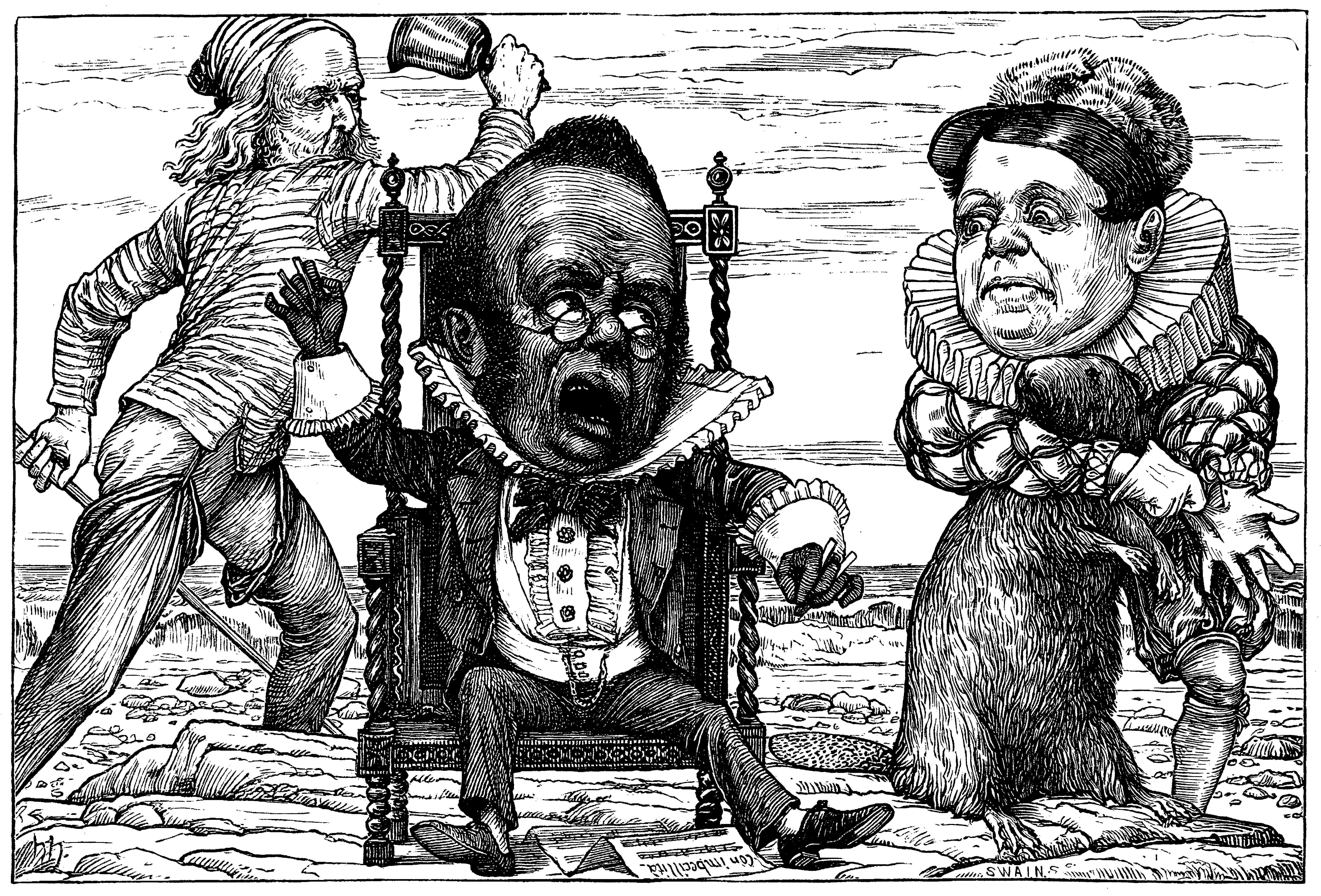

THE BANKER’S FATE

489 They sought it with thimbles, they sought it with care;

490

They pursued it with forks and hope;

491

They threatened its life with a railway-share;

492

They charmed it with smiles and soap.

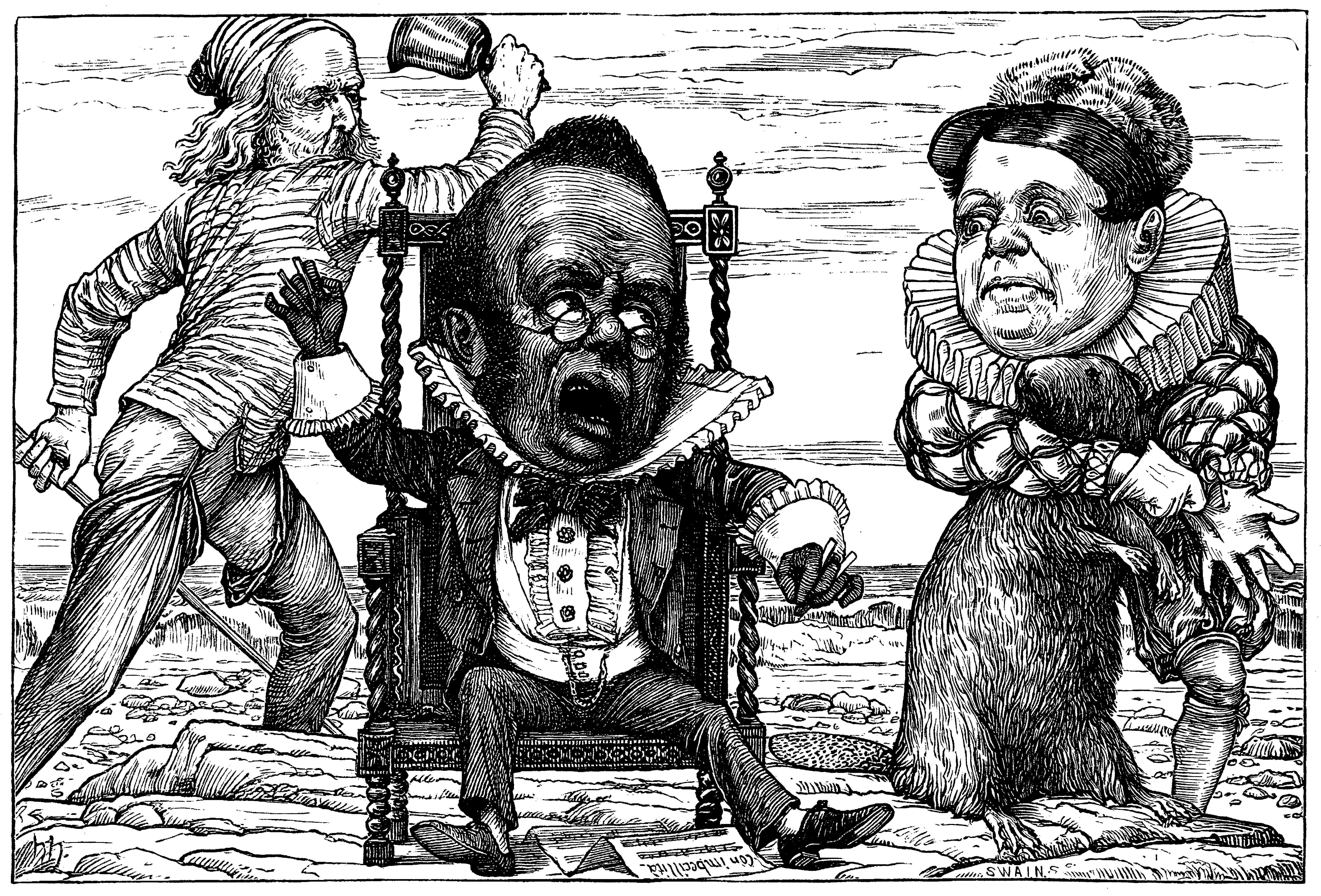

493 And the Banker, inspired with a courage so new

494

It was matter for general remark,

495

Rushed madly ahead and was lost to their view

496

In his zeal to discover the Snark

497 But while he was seeking with thimbles and care,

498

A Bandersnatch swiftly drew nigh

499

And grabbed at the Banker, who shrieked in despair,

500

For he knew it was useless to fly.

501 He offered large discount —he offered a cheque

502

(Drawn “to bearer”) for seven-pounds-ten:

503

But the Bandersnatch merely extended its neck

504

And grabbed at the Banker again.

505 Without rest or pause —while those frumious jaws

506

Went savagely snapping around-

507

He skipped and he hopped, and he floundered and flopped,

508

Till fainting he fell to the ground.

509 The Bandersnatch fled as the others appeared

510

Led on by that fear-stricken yell:

511

And the Bellman remarked “It is just as I feared!”

512

And solemnly tolled on his bell.

513 He was black in the face, and they scarcely could trace

514

The least likeness to what he had been:

515

While so great was his fright that his waistcoat turned white —

516

A wonderful thing to be seen!

517 To the horror of all who were present that day.

518

He uprose in full evening dress,

519

And with senseless grimaces endeavoured to say

520

What his tongue could no longer express.

521 Down he sank in a chair —ran his hands through his hair —

522

And chanted in mimsiest tones

523

Words whose utter inanity proved his insanity,

524

While he rattled a couple of bones.

525 “Leave him here to his fate —it is getting so late!”

526

The Bellman exclaimed in a fright.

527

“We have lost half the day. Any further delay,

528

And we sha’nt catch a Snark before night!”

Fit the Eighth

529 They sought it with thimbles, they sought it with care;

530

They pursued it with forks and hope;

531

They threatened its life with a railway-share;

532

They charmed it with smiles and soap.

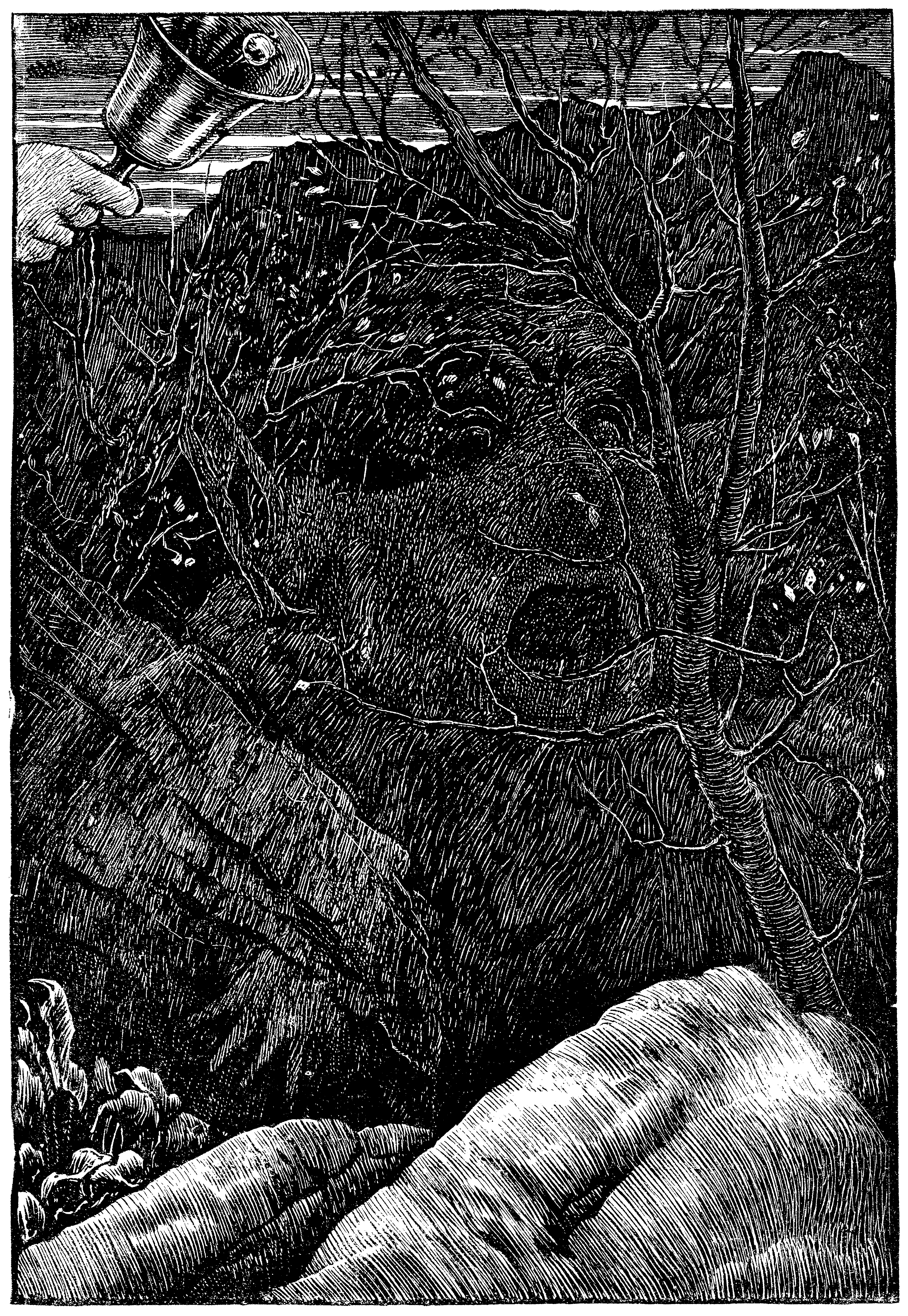

533 They shuddered to think that the chase might fail,

534

And the Beaver, excited at last,

535

Went bounding along on the tip of its tail,

536

For the daylight was nearly past.

537 “There is Thingumbob shouting!” the Bellman said,

538

“He is shouting like mad, only hark!

539

He is waving his hands, he is wagging his head,

540

He has certainly found a Snark!”

541 They gazed in delight, while the Butcher exclaimed

542

“He was always a desperate wag!”

543

They beheld him —their Baker —their hero unnamed —

544

On the top of a neighbouring crag.

545 Erect and sublime, for one moment of time.

546

In the next, that wild figure they saw

547

(As if stung by a spasm) plunge into a chasm,

548

While they waited and listened in awe.

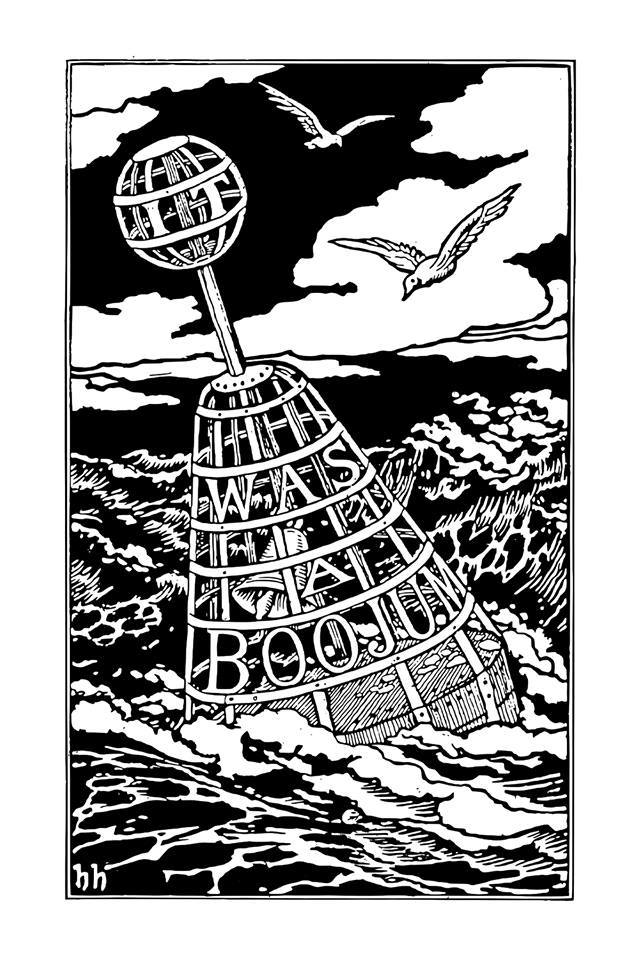

549 “It’s a Snark!” was the sound that first came to their ears,

550

And seemed almost too good to be true.

551

Then followed a torrent of laughter and cheers:

552

Then the ominous words “It’s a Boo-”

553 Then, silence. Some fancied they heard in the air

554

A weary and wandering sigh

555

That sounded like “-jum!” but the others declare

556

It was only a breeze that went by.

557 They hunted till darkness came on, but they found

558

Not a button, or feather, or mark,

559

By which they could tell that they stood on the ground

560

Where the Baker had met with the Snark.

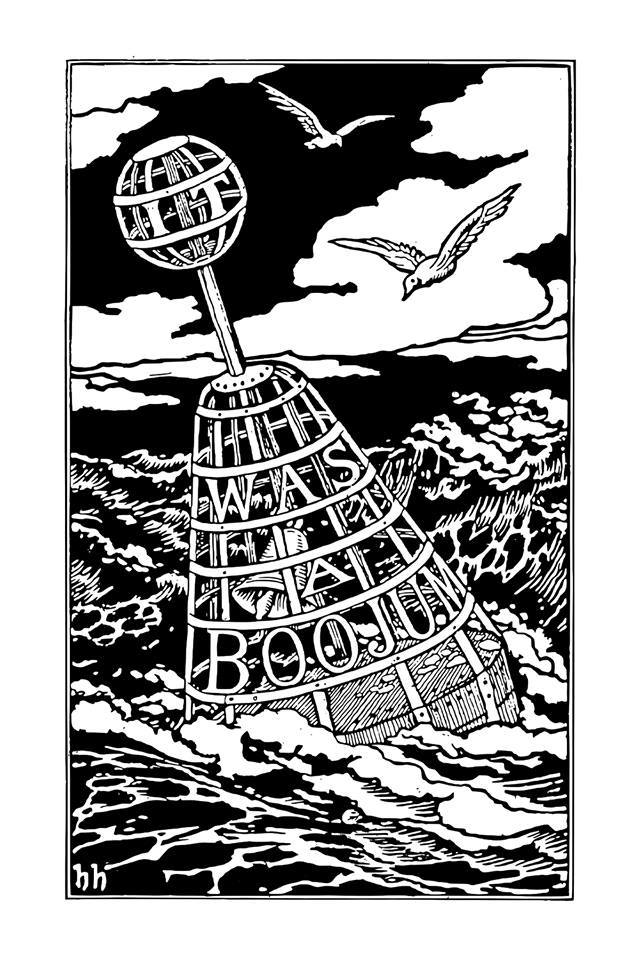

561 In the midst of the word he was trying to say,

562

In the midst of his laughter and glee,

563

He had softly and suddenly vanished away —

564

For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.

SNARK FOOD

"All art is infested by other art."

Leo Steinberg in Art about Art, 1979

"It is possible that the author was half-consciously laying a trap, so readily did he take to the inventing of puzzles and things enigmatic; but to those who knew the man, or who have divined him correctly through his writings, the explanation is fairly simple."

Henry Holiday, 1898-01-29, on Lewis Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark

"We have neglected the gift of comprehending things through our senses. Concept is divorced from percept, and thought moves among abstractions. Our eyes have been reduced to instruments with which to identify and to measure; hence we suffer a paucity of ideas that can be expressed in images and in an incapacity to discover meaning in what we see. Naturally we feel lost in the presence of objects that make sense only to undiluted vision, and we seek refuge in the more familiar medium of words. ... The inborn capacity to understand through the eyes has been put to sleep and must be reawakened."

Rudolf Arnheim: Art and Visual Perception, 1974, p. 1

"Only those questions that are in principle undecidable, we can decide."

Heinz von Foerster: Ethics and Second-Order Cybernetics,

Système et thérapie familiale, Paris, 1990-10-04

"L.C. has forgotten that 'the Snark' is a tragedy"

Henry Holiday (his handwritten note to a letter from L. Carroll), 1876

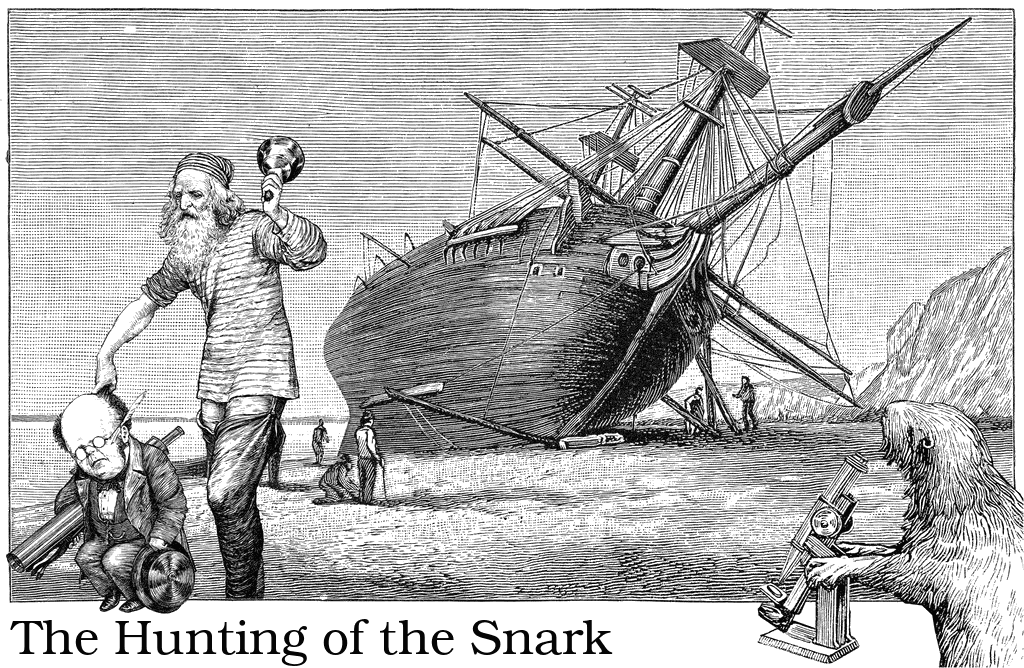

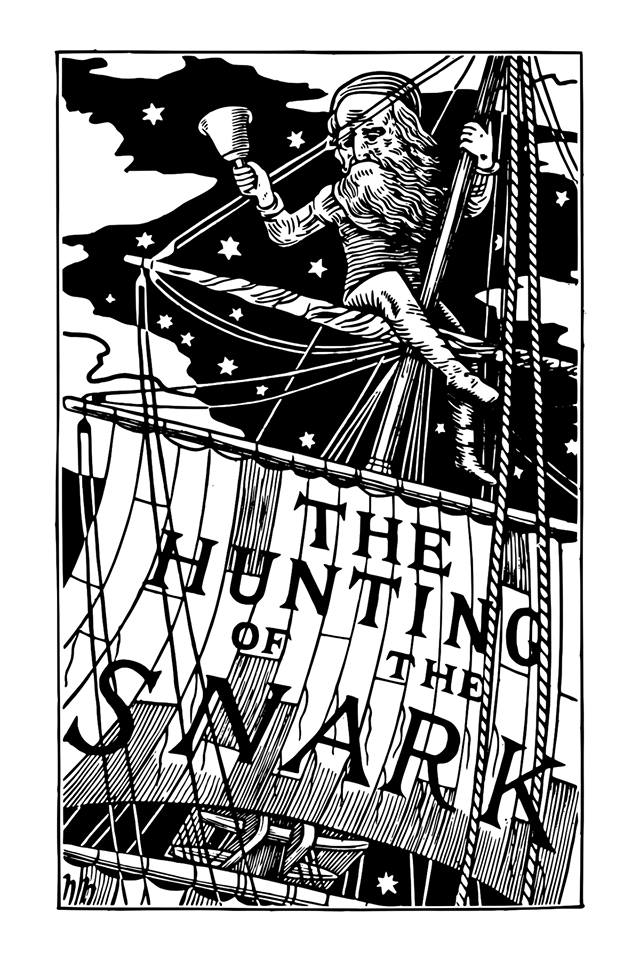

The original verson of this web edition is based on

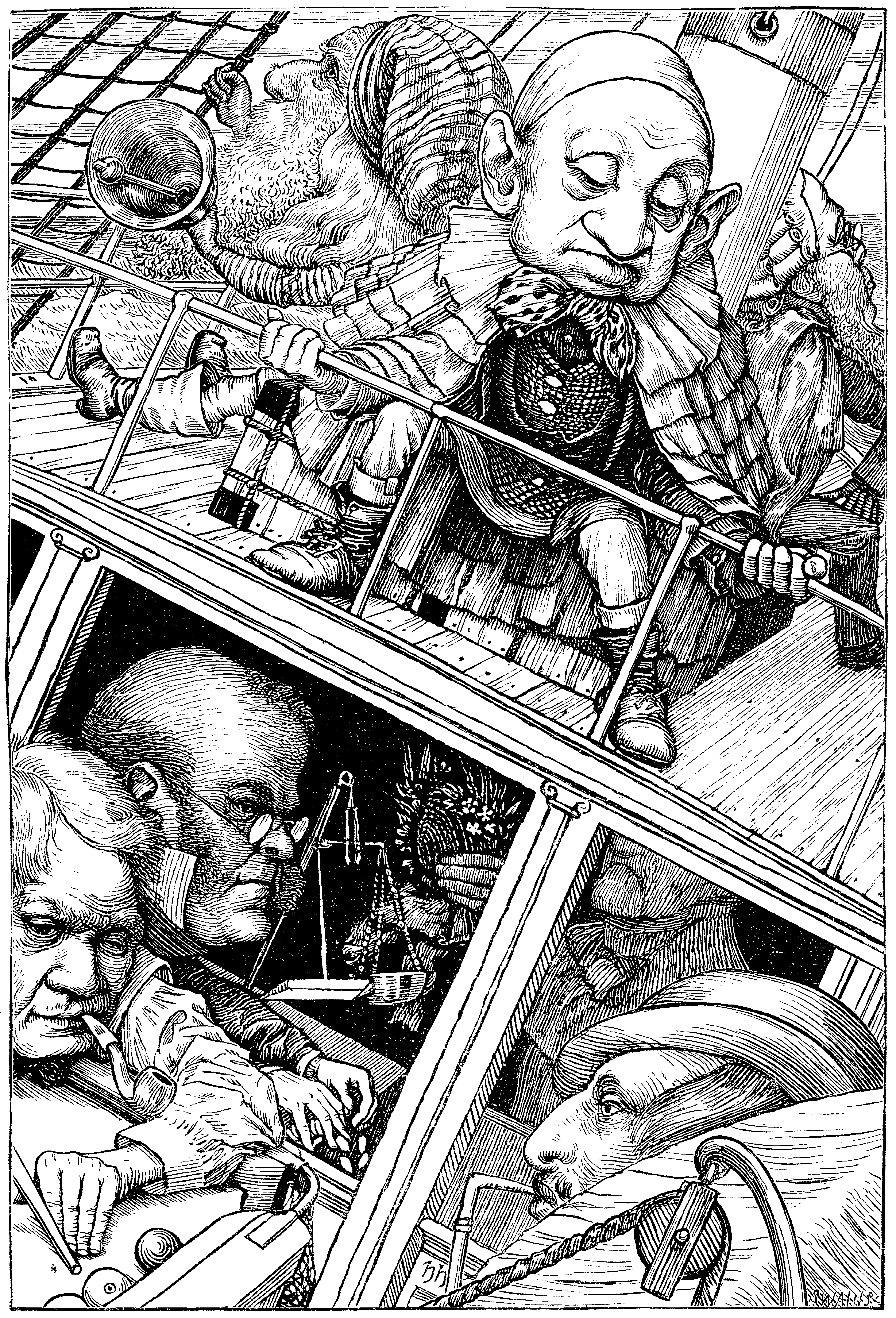

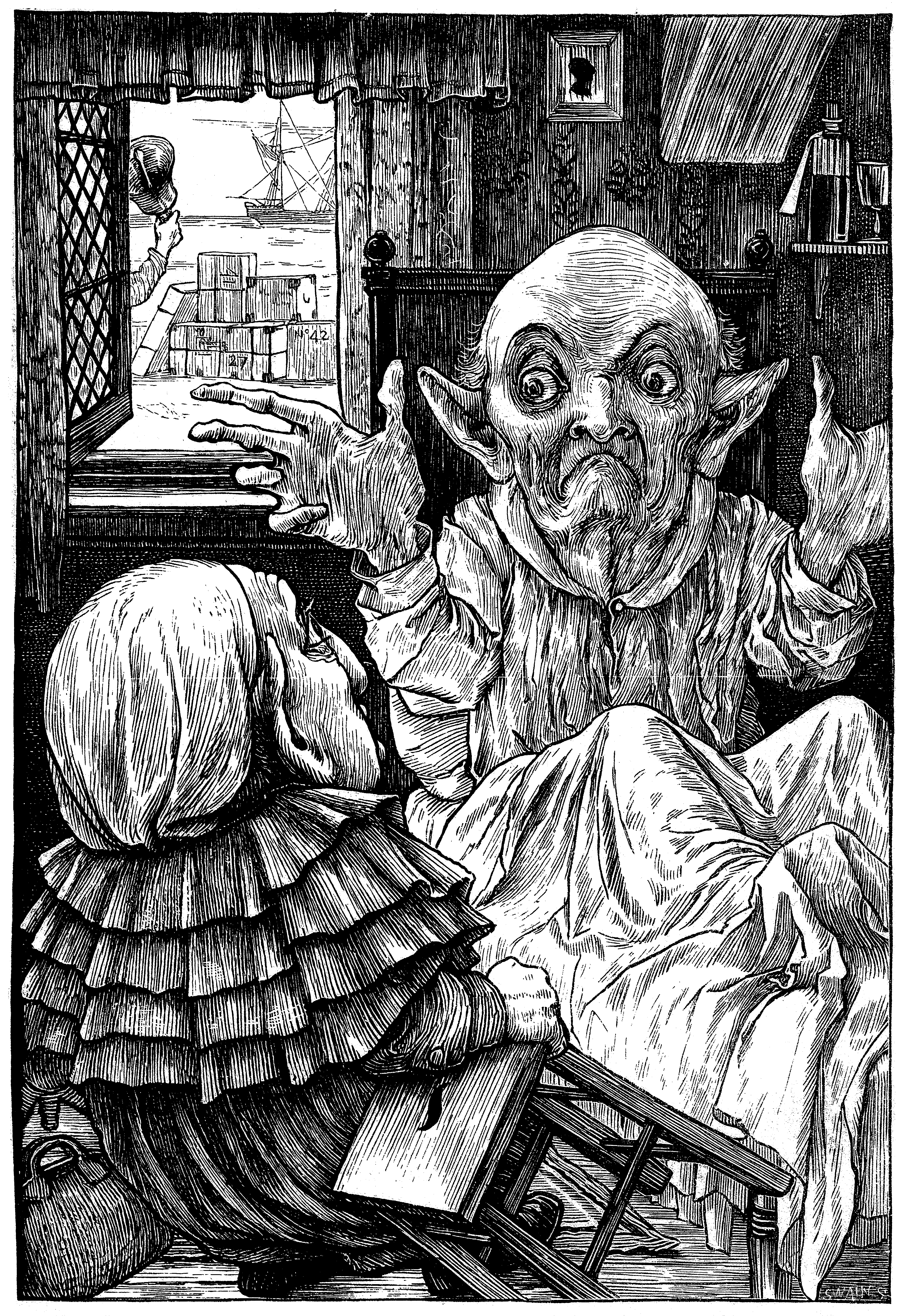

The Hunting of the Snark : An Agony, in eight Fits / by Lewis Carroll;

with nine illustrations by Henry Holiday. London : Macmillan, 1876,

published on-line by:

eBooks@Adelaide

The University of Adelaide Library

University of Adelaide

South Australia 5005

Save